Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Quasi-Experimental Research

38 One-Group Designs

Learning objectives.

- Explain what quasi-experimental research is and distinguish it clearly from both experimental and correlational research.

- Describe three different types of one-group quasi-experimental designs.

- Identify the threats to internal validity associated with each of these designs.

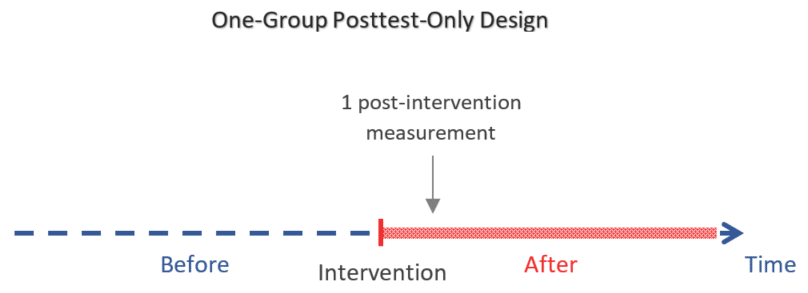

One-Group Posttest Only Design

In a one-group posttest only design , a treatment is implemented (or an independent variable is manipulated) and then a dependent variable is measured once after the treatment is implemented. Imagine, for example, a researcher who is interested in the effectiveness of an anti-drug education program on elementary school students’ attitudes toward illegal drugs. The researcher could implement the anti-drug program, and then immediately after the program ends, the researcher could measure students’ attitudes toward illegal drugs.

This is the weakest type of quasi-experimental design. A major limitation to this design is the lack of a control or comparison group. There is no way to determine what the attitudes of these students would have been if they hadn’t completed the anti-drug program. Despite this major limitation, results from this design are frequently reported in the media and are often misinterpreted by the general population. For instance, advertisers might claim that 80% of women noticed their skin looked bright after using Brand X cleanser for a month. If there is no comparison group, then this statistic means little to nothing.

One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

In a one-group pretest-posttest design , the dependent variable is measured once before the treatment is implemented and once after it is implemented. Let’s return to the example of a researcher who is interested in the effectiveness of an anti-drug education program on elementary school students’ attitudes toward illegal drugs. The researcher could measure the attitudes of students at a particular elementary school during one week, implement the anti-drug program during the next week, and finally, measure their attitudes again the following week. The pretest-posttest design is much like a within-subjects experiment in which each participant is tested first under the control condition and then under the treatment condition. It is unlike a within-subjects experiment, however, in that the order of conditions is not counterbalanced because it typically is not possible for a participant to be tested in the treatment condition first and then in an “untreated” control condition.

If the average posttest score is better than the average pretest score (e.g., attitudes toward illegal drugs are more negative after the anti-drug educational program), then it makes sense to conclude that the treatment might be responsible for the improvement. Unfortunately, one often cannot conclude this with a high degree of certainty because there may be other explanations for why the posttest scores may have changed. These alternative explanations pose threats to internal validity.

One alternative explanation goes under the name of history . Other things might have happened between the pretest and the posttest that caused a change from pretest to posttest. Perhaps an anti-drug program aired on television and many of the students watched it, or perhaps a celebrity died of a drug overdose and many of the students heard about it.

Another alternative explanation goes under the name of maturation . Participants might have changed between the pretest and the posttest in ways that they were going to anyway because they are growing and learning. If it were a year long anti-drug program, participants might become less impulsive or better reasoners and this might be responsible for the change in their attitudes toward illegal drugs.

Another threat to the internal validity of one-group pretest-posttest designs is testing , which refers to when the act of measuring the dependent variable during the pretest affects participants’ responses at posttest. For instance, completing the measure of attitudes towards illegal drugs may have had an effect on those attitudes. Simply completing this measure may have inspired further thinking and conversations about illegal drugs that then produced a change in posttest scores.

Similarly, instrumentation can be a threat to the internal validity of studies using this design. Instrumentation refers to when the basic characteristics of the measuring instrument change over time. When human observers are used to measure behavior, they may over time gain skill, become fatigued, or change the standards on which observations are based. So participants may have taken the measure of attitudes toward illegal drugs very seriously during the pretest when it was novel but then they may have become bored with the measure at posttest and been less careful in considering their responses.

Another alternative explanation for a change in the dependent variable in a pretest-posttest design is regression to the mean . This refers to the statistical fact that an individual who scores extremely high or extremely low on a variable on one occasion will tend to score less extremely on the next occasion. For example, a bowler with a long-term average of 150 who suddenly bowls a 220 will almost certainly score lower in the next game. Her score will “regress” toward her mean score of 150. Regression to the mean can be a problem when participants are selected for further study because of their extreme scores. Imagine, for example, that only students who scored especially high on the test of attitudes toward illegal drugs (those with extremely favorable attitudes toward drugs) were given the anti-drug program and then were retested. Regression to the mean all but guarantees that their scores will be lower at the posttest even if the training program has no effect.

A closely related concept—and an extremely important one in psychological research—is spontaneous remission . This is the tendency for many medical and psychological problems to improve over time without any form of treatment. The common cold is a good example. If one were to measure symptom severity in 100 common cold sufferers today, give them a bowl of chicken soup every day, and then measure their symptom severity again in a week, they would probably be much improved. This does not mean that the chicken soup was responsible for the improvement, however, because they would have been much improved without any treatment at all. The same is true of many psychological problems. A group of severely depressed people today is likely to be less depressed on average in 6 months. In reviewing the results of several studies of treatments for depression, researchers Michael Posternak and Ivan Miller found that participants in waitlist control conditions improved an average of 10 to 15% before they received any treatment at all (Posternak & Miller, 2001) [1] . Thus one must generally be very cautious about inferring causality from pretest-posttest designs.

A common approach to ruling out the threats to internal validity described above is by revisiting the research design to include a control group, one that does not receive the treatment effect. A control group would be subject to the same threats from history, maturation, testing, instrumentation, regression to the mean, and spontaneous remission and so would allow the researcher to measure the actual effect of the treatment (if any). Of course, including a control group would mean that this is no longer a one-group design.

Does Psychotherapy Work?

Early studies on the effectiveness of psychotherapy tended to use pretest-posttest designs. In a classic 1952 article, researcher Hans Eysenck summarized the results of 24 such studies showing that about two thirds of patients improved between the pretest and the posttest (Eysenck, 1952) [2] . But Eysenck also compared these results with archival data from state hospital and insurance company records showing that similar patients recovered at about the same rate without receiving psychotherapy. This parallel suggested to Eysenck that the improvement that patients showed in the pretest-posttest studies might be no more than spontaneous remission. Note that Eysenck did not conclude that psychotherapy was ineffective. He merely concluded that there was no evidence that it was, and he wrote of “the necessity of properly planned and executed experimental studies into this important field” (p. 323). You can read the entire article here:

http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Eysenck/psychotherapy.htm

Fortunately, many other researchers took up Eysenck’s challenge, and by 1980 hundreds of experiments had been conducted in which participants were randomly assigned to treatment and control conditions, and the results were summarized in a classic book by Mary Lee Smith, Gene Glass, and Thomas Miller (Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980) [3] . They found that overall psychotherapy was quite effective, with about 80% of treatment participants improving more than the average control participant. Subsequent research has focused more on the conditions under which different types of psychotherapy are more or less effective.

Interrupted Time Series Design

A variant of the pretest-posttest design is the interrupted time-series desig n . A time series is a set of measurements taken at intervals over a period of time. For example, a manufacturing company might measure its workers’ productivity each week for a year. In an interrupted time series-design, a time series like this one is “interrupted” by a treatment. In one classic example, the treatment was the reduction of the work shifts in a factory from 10 hours to 8 hours (Cook & Campbell, 1979) [4] . Because productivity increased rather quickly after the shortening of the work shifts, and because it remained elevated for many months afterward, the researcher concluded that the shortening of the shifts caused the increase in productivity. Notice that the interrupted time-series design is like a pretest-posttest design in that it includes measurements of the dependent variable both before and after the treatment. It is unlike the pretest-posttest design, however, in that it includes multiple pretest and posttest measurements.

Figure 8.1 shows data from a hypothetical interrupted time-series study. The dependent variable is the number of student absences per week in a research methods course. The treatment is that the instructor begins publicly taking attendance each day so that students know that the instructor is aware of who is present and who is absent. The top panel of Figure 8.1 shows how the data might look if this treatment worked. There is a consistently high number of absences before the treatment, and there is an immediate and sustained drop in absences after the treatment. The bottom panel of Figure 8.1 shows how the data might look if this treatment did not work. On average, the number of absences after the treatment is about the same as the number before. This figure also illustrates an advantage of the interrupted time-series design over a simpler pretest-posttest design. If there had been only one measurement of absences before the treatment at Week 7 and one afterward at Week 8, then it would have looked as though the treatment were responsible for the reduction. The multiple measurements both before and after the treatment suggest that the reduction between Weeks 7 and 8 is nothing more than normal week-to-week variation.

Image Descriptions

Figure 8.1 image description: Two line graphs charting the number of absences per week over 14 weeks. The first 7 weeks are without treatment and the last 7 weeks are with treatment. In the first line graph, there are between 4 to 8 absences each week. After the treatment, the absences drop to 0 to 3 each week, which suggests the treatment worked. In the second line graph, there is no noticeable change in the number of absences per week after the treatment, which suggests the treatment did not work. [Return to Figure 8.1]

- Posternak, M. A., & Miller, I. (2001). Untreated short-term course of major depression: A meta-analysis of studies using outcomes from studies using wait-list control groups. Journal of Affective Disorders, 66 , 139–146. ↵

- Eysenck, H. J. (1952). The effects of psychotherapy: An evaluation. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 16 , 319–324. ↵

- Smith, M. L., Glass, G. V., & Miller, T. I. (1980). The benefits of psychotherapy . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↵

- Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design & analysis issues in field settings . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ↵

A treatment is implemented (or an independent variable is manipulated) and then a dependent variable is measured once after the treatment is implemented.

An experiment design in which the dependent variable is measured once before the treatment is implemented and once after it is implemented.

Events outside of the pretest-posttest research design that might have influenced many or all of the participants between the pretest and the posttest.

Participants might have changed between the pretest and the posttest in ways that they were going to anyway because they are growing and learning.

A threat to internal validity that occurs when the measurement of the dependent variable during the pretest affects participants' responses at posttest.

A potential threat to internal validity when the basic characteristics of the measuring instrument change over the course of the study.

Refers to the statistical fact that an individual who scores extremely high or extremely low on a variable on one occasion will tend to score less extremely on the next occasion.

The tendency for many medical and psychological problems to improve over time without any form of treatment.

A set of measurements taken at intervals over a period of time that is "interrupted" by a treatment.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Experimental Design: Types, Examples & Methods

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to different groups in an experiment. Types of design include repeated measures, independent groups, and matched pairs designs.

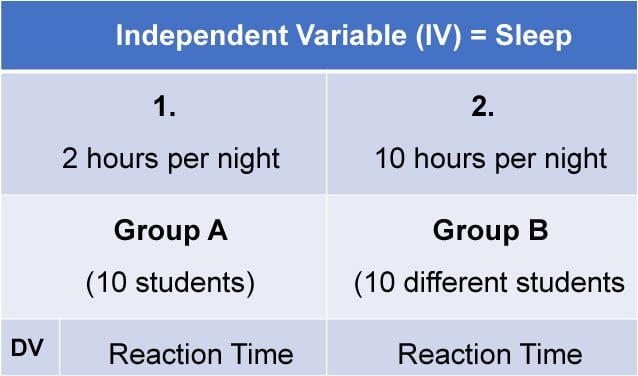

Probably the most common way to design an experiment in psychology is to divide the participants into two groups, the experimental group and the control group, and then introduce a change to the experimental group, not the control group.

The researcher must decide how he/she will allocate their sample to the different experimental groups. For example, if there are 10 participants, will all 10 participants participate in both groups (e.g., repeated measures), or will the participants be split in half and take part in only one group each?

Three types of experimental designs are commonly used:

1. Independent Measures

Independent measures design, also known as between-groups , is an experimental design where different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable. This means that each condition of the experiment includes a different group of participants.

This should be done by random allocation, ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to one group.

Independent measures involve using two separate groups of participants, one in each condition. For example:

- Con : More people are needed than with the repeated measures design (i.e., more time-consuming).

- Pro : Avoids order effects (such as practice or fatigue) as people participate in one condition only. If a person is involved in several conditions, they may become bored, tired, and fed up by the time they come to the second condition or become wise to the requirements of the experiment!

- Con : Differences between participants in the groups may affect results, for example, variations in age, gender, or social background. These differences are known as participant variables (i.e., a type of extraneous variable ).

- Control : After the participants have been recruited, they should be randomly assigned to their groups. This should ensure the groups are similar, on average (reducing participant variables).

2. Repeated Measures Design

Repeated Measures design is an experimental design where the same participants participate in each independent variable condition. This means that each experiment condition includes the same group of participants.

Repeated Measures design is also known as within-groups or within-subjects design .

- Pro : As the same participants are used in each condition, participant variables (i.e., individual differences) are reduced.

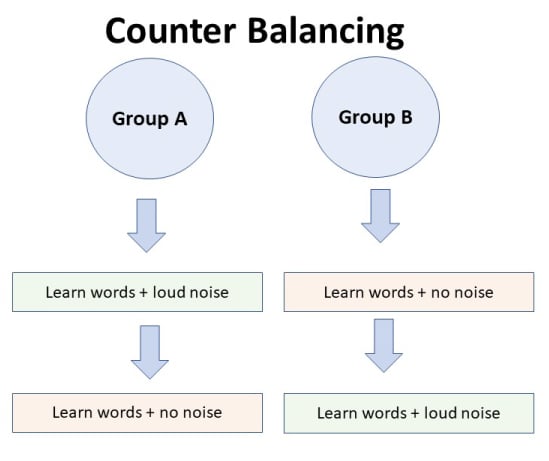

- Con : There may be order effects. Order effects refer to the order of the conditions affecting the participants’ behavior. Performance in the second condition may be better because the participants know what to do (i.e., practice effect). Or their performance might be worse in the second condition because they are tired (i.e., fatigue effect). This limitation can be controlled using counterbalancing.

- Pro : Fewer people are needed as they participate in all conditions (i.e., saves time).

- Control : To combat order effects, the researcher counter-balances the order of the conditions for the participants. Alternating the order in which participants perform in different conditions of an experiment.

Counterbalancing

Suppose we used a repeated measures design in which all of the participants first learned words in “loud noise” and then learned them in “no noise.”

We expect the participants to learn better in “no noise” because of order effects, such as practice. However, a researcher can control for order effects using counterbalancing.

The sample would be split into two groups: experimental (A) and control (B). For example, group 1 does ‘A’ then ‘B,’ and group 2 does ‘B’ then ‘A.’ This is to eliminate order effects.

Although order effects occur for each participant, they balance each other out in the results because they occur equally in both groups.

3. Matched Pairs Design

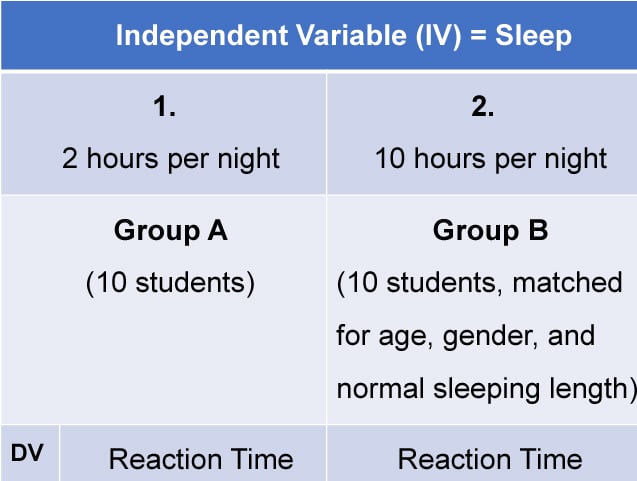

A matched pairs design is an experimental design where pairs of participants are matched in terms of key variables, such as age or socioeconomic status. One member of each pair is then placed into the experimental group and the other member into the control group .

One member of each matched pair must be randomly assigned to the experimental group and the other to the control group.

- Con : If one participant drops out, you lose 2 PPs’ data.

- Pro : Reduces participant variables because the researcher has tried to pair up the participants so that each condition has people with similar abilities and characteristics.

- Con : Very time-consuming trying to find closely matched pairs.

- Pro : It avoids order effects, so counterbalancing is not necessary.

- Con : Impossible to match people exactly unless they are identical twins!

- Control : Members of each pair should be randomly assigned to conditions. However, this does not solve all these problems.

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to an experiment’s different conditions (or IV levels). There are three types:

1. Independent measures / between-groups : Different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable.

2. Repeated measures /within groups : The same participants take part in each condition of the independent variable.

3. Matched pairs : Each condition uses different participants, but they are matched in terms of important characteristics, e.g., gender, age, intelligence, etc.

Learning Check

Read about each of the experiments below. For each experiment, identify (1) which experimental design was used; and (2) why the researcher might have used that design.

1 . To compare the effectiveness of two different types of therapy for depression, depressed patients were assigned to receive either cognitive therapy or behavior therapy for a 12-week period.

The researchers attempted to ensure that the patients in the two groups had similar severity of depressed symptoms by administering a standardized test of depression to each participant, then pairing them according to the severity of their symptoms.

2 . To assess the difference in reading comprehension between 7 and 9-year-olds, a researcher recruited each group from a local primary school. They were given the same passage of text to read and then asked a series of questions to assess their understanding.

3 . To assess the effectiveness of two different ways of teaching reading, a group of 5-year-olds was recruited from a primary school. Their level of reading ability was assessed, and then they were taught using scheme one for 20 weeks.

At the end of this period, their reading was reassessed, and a reading improvement score was calculated. They were then taught using scheme two for a further 20 weeks, and another reading improvement score for this period was calculated. The reading improvement scores for each child were then compared.

4 . To assess the effect of the organization on recall, a researcher randomly assigned student volunteers to two conditions.

Condition one attempted to recall a list of words that were organized into meaningful categories; condition two attempted to recall the same words, randomly grouped on the page.

Experiment Terminology

Ecological validity.

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

Demand characteristics

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables which are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. Extraneous variables should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of taking part in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.

One-Group Posttest Only Design: An Introduction

The one-group posttest-only design (a.k.a. one-shot case study ) is a type of quasi-experiment in which the outcome of interest is measured only once after exposing a non-random group of participants to a certain intervention.

The objective is to evaluate the effect of that intervention which can be:

- A training program

- A policy change

- A medical treatment, etc.

As in other quasi-experiments, the group of participants who receive the intervention is selected in a non-random way (for example according to their choosing or that of the researcher).

The one-group posttest-only design is especially characterized by having:

- No control group

- No measurements before the intervention

It is the simplest and weakest of the quasi-experimental designs in terms of level of evidence as the measured outcome cannot be compared to a measurement before the intervention nor to a control group.

So the outcome will be compared to what we assume will happen if the intervention was not implemented. This is generally based on expert knowledge and speculation.

Next we will discuss cases where this design can be useful and its limitations in the study of a causal relationship between the intervention and the outcome.

Advantages and Limitations of the one-group posttest-only design

Advantages of the one-group posttest-only design, 1. advantages related to the non-random selection of participants:.

- Ethical considerations: Random selection of participants is considered unethical when the intervention is believed to be harmful (for example exposing people to smoking or dangerous chemicals) or on the contrary when it is believed to be so beneficial that it would be malevolent not to offer it to all participants (for example a groundbreaking treatment or medical operation).

- Difficulty to adequately randomize subjects and locations: In some cases where the intervention acts on a group of people at a given location, it becomes infeasible to adequately randomize subjects (ex. an intervention that reduces pollution in a given area).

2. Advantages related to the simplicity of this design:

- Feasible with fewer resources than most designs: The one-group posttest-only design is especially useful when the intervention must be quickly introduced and we do not have enough time to take pre-intervention measurements. Other designs may also require a larger sample size or a higher cost to account for the follow-up of a control group.

- No temporality issue: Since the outcome is measured after the intervention, we can be certain that it occurred after it, which is important for inferring a causal relationship between the two.

Limitations of the one-group posttest-only design

1. selection bias:.

Because participants were not chosen at random, it is certainly possible that those who volunteered are not representative of the population of interest on which we intend to draw our conclusions.

2. Limitation due to maturation:

Because we don’t have a control group nor a pre-intervention measurement of the variable of interest, the post-intervention measurement will be compared to what we believe or assume would happen was there no intervention at all.

The problem is when the outcome of interest has a natural fluctuation pattern (maturation effect) that we don’t know about.

So since certain factors are essentially hard to predict and since 1 measurement is certainly not enough to understand the natural pattern of an outcome, therefore with the one-group posttest-only design, we can hardly infer any causal relationship between intervention and outcome.

3. Limitation due to history:

The idea here is that we may have a historical event, which may also influence the outcome, occurring at the same time as the intervention.

The problem is that this event can now be an alternative explanation of the observed outcome. The only way out of this is if the effect of this event on the outcome is well-known and documented in order to account for it in our data analysis.

This is why most of the time we prefer other designs that include a control group (made of people who were exposed to the historical event but not to the intervention) as it provides us with a reference to compare to.

Example of a study that used the one-group posttest-only design

In 2018, Tsai et al. designed an exercise program for older adults based on traditional Chinese medicine ideas, and wanted to test its feasibility, safety and helpfulness.

So they conducted a one-group posttest-only study as a pilot test with 31 older adult volunteers. Then they evaluated these participants (using open-ended questions) after receiving the intervention (the exercise program).

The study concluded that the program was safe, helpful and suitable for older adults.

What can we learn from this example?

1. work within the design limitations:.

Notice that the outcome measured was the feasibility of the program and not its health effects on older adults.

The purpose of the study was to design an exercise program based on the participants’ feedback. So a pilot one-group posttest-only study was enough to do so.

For studying the health effects of this program on older adults a randomized controlled trial will certainly be necessary.

2. Be careful with generalization when working with non-randomly selected participants:

For instance, participants who volunteered to be in this study were all physically active older adults who exercise regularly.

Therefore, the study results may not generalize to all the elderly population.

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference . 2nd Edition. Cengage Learning; 2001.

- Campbell DT, Stanley J. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research . 1st Edition. Cengage Learning; 1963.

Further reading

- Understand Quasi-Experimental Design Through an Example

- Experimental vs Quasi-Experimental Design

- Static-Group Comparison Design

- One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

Doc’s Things and Stuff

one-group pretest-posttest design | Definition

The one-group pretest-posttest design measures changes in a single group before and after an intervention, assessing its effect without a control group.

Introduction to the One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

In social science research, the one-group pretest-posttest design is a commonly used experimental design to assess the impact of an intervention or treatment on a single group. This design involves measuring the participants on certain variables before and after an intervention to evaluate any resulting changes. Despite being a straightforward method, this design has specific strengths and limitations, particularly in terms of internal validity, because it lacks a control group for comparison.

The one-group pretest-posttest design is widely used in fields like psychology, education, and health sciences, where researchers may be interested in testing an intervention’s immediate impact on a group but may not have the resources or ability to create a control group.

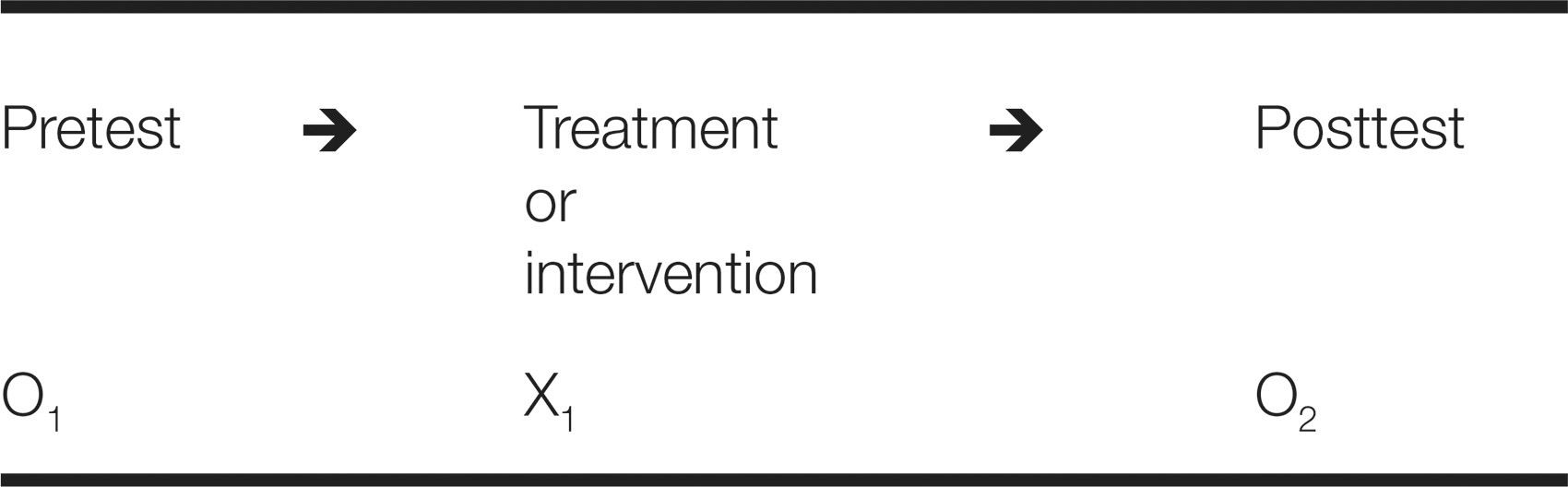

Structure of the One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

The one-group pretest-posttest design includes three primary steps:

- Pretest (Baseline Measurement) : The researcher measures the dependent variable in the group before the intervention. This serves as a baseline to compare post-intervention changes.

- Intervention : The treatment or intervention is administered to the group. This intervention is expected to influence the dependent variable, prompting change.

- Posttest (Follow-up Measurement) : After the intervention, the researcher measures the dependent variable again. By comparing pretest and posttest results, researchers assess the intervention’s effect.

This design is often symbolized as:

- O1 represents the pretest measurement,

- X represents the intervention, and

- O2 represents the posttest measurement.

Advantages of the One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

The simplicity and ease of the one-group pretest-posttest design make it a useful option for evaluating interventions, especially in exploratory studies. Its main advantages include:

- Cost-Effectiveness : The design is relatively inexpensive and easy to implement since it only requires one group.

- Practical for Small Studies : It is particularly useful in smaller studies or pilot tests where a control group may be impractical.

- Helps Measure Change : By having pretest and posttest measures, researchers can detect changes in the dependent variable and establish baseline data against which the intervention’s effect is evaluated.

- Useful in Natural Settings : This design can be implemented in natural, real-world settings, making it suitable for field studies where random assignment to groups may not be feasible.

Limitations of the One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

Despite its usefulness, the one-group pretest-posttest design has significant limitations, particularly concerning its internal validity. The absence of a control group makes it challenging to isolate the intervention’s effect from other variables that could influence the results. Key limitations include:

- Lack of a Control Group : Without a control group, it’s difficult to determine if changes in the dependent variable are due to the intervention or other external factors.

- Susceptibility to Confounding Variables : Several external or internal factors may influence participants between the pretest and posttest, potentially confounding the results. These include maturation, history, and testing effects.

- Difficulty in Causal Inference : Because the design cannot fully control for external influences, it is challenging to make strong causal claims. The design can suggest an association between the intervention and outcomes, but causation remains uncertain.

- Testing Effects : Pretesting itself can influence participants’ responses in the posttest. For instance, if participants become familiar with the test, they may perform better in the posttest regardless of the intervention’s actual effect.

Threats to Validity in One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

The one-group pretest-posttest design is susceptible to several threats to internal validity, which refer to factors that could lead to misinterpretation of the intervention’s effect.

1. History Effects

History refers to external events that occur between the pretest and posttest and may impact participants. For example, if a health awareness campaign runs in the community during a study on health behavior, participants’ posttest responses might reflect both the campaign’s influence and the intervention’s effect.

2. Maturation Effects

Maturation refers to natural changes in participants over time. In studies with long gaps between the pretest and posttest, participants may develop or change in ways unrelated to the intervention. For instance, children in a study on reading skills may improve simply as they age and gain more exposure to reading material, not necessarily due to the intervention.

3. Testing Effects

Testing effects occur when the act of taking the pretest influences posttest outcomes. This is common in educational and psychological research, where familiarity with the test can lead to improved scores without the intervention’s influence. For example, participants may recall their previous answers or improve their performance because of repeated exposure.

4. Instrumentation Effects

Instrumentation effects arise when there are inconsistencies in measurement tools or methods between the pretest and posttest. Changes in the instrument (e.g., different test versions) can affect results. For instance, if a teacher evaluates students’ performance more strictly in the pretest than in the posttest, score changes may reflect evaluation inconsistency rather than learning progress.

5. Regression to the Mean

Regression to the mean occurs when participants with extreme pretest scores tend to have less extreme posttest scores, moving closer to the average over time. This can create the illusion of improvement or decline. For example, a group of students who score particularly low on a pretest may improve on the posttest simply because extreme scores tend to balance out over time.

Example of the One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design in Practice

Imagine a researcher is evaluating a program designed to improve stress management among college students during exams. The steps might include:

- Pretest : The researcher administers a stress questionnaire to measure baseline stress levels.

- Intervention : Students attend a stress management workshop focusing on relaxation and time management techniques.

- Posttest : The same questionnaire is administered after the exam period to assess any change in stress levels.

By comparing pretest and posttest scores, the researcher hopes to determine if the workshop reduced students’ stress. However, without a control group, it is difficult to confirm if any reduction in stress levels is due solely to the workshop or other factors, such as students naturally adapting to exam stress over time.

Alternatives and Modifications to Strengthen Validity

To address some of the limitations of the one-group pretest-posttest design, researchers can consider alternatives or add elements that enhance internal validity:

1. Add a Control Group

Adding a control group creates a two-group pretest-posttest design , where one group receives the intervention and the other does not. This provides a comparison point, helping researchers isolate the intervention’s effect.

2. Use Time-Series Design

A time-series design involves multiple measurements before and after the intervention, helping detect patterns and rule out some confounding effects like maturation or history.

3. Implement Delayed Intervention

With a delayed intervention or waitlist design, all participants eventually receive the intervention, but at different times. This approach allows for comparisons between groups during the period when only one group has received the intervention.

4. Use Statistical Controls

In some cases, statistical controls like covariate analysis can help adjust for potential confounding factors. Researchers can control for variables like age or baseline levels of the dependent variable to help isolate the intervention’s effect.

The one-group pretest-posttest design is a useful experimental setup for assessing an intervention’s impact on a single group. Its simplicity and cost-effectiveness make it valuable for exploratory research, pilot studies, and situations where resources for a control group are limited. However, researchers must carefully consider its limitations, particularly the threat to internal validity. By understanding and addressing these limitations through alternative designs or statistical methods, researchers can better interpret their findings and ensure that their conclusions about an intervention’s effects are as accurate as possible.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Reader's guide

Entries a-z, subject index.

- One-Group Pretest–Posttest Design

- By: Gregory A. Cranmer

- In: The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods

- Chapter DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781483381411.n388

- Subject: Communication and Media Studies , Sociology

- Show page numbers Hide page numbers

A one-group pretest–posttest design is a type of research design that is most often utilized by behavioral researchers to determine the effect of a treatment or intervention on a given sample. This research design is characterized by two features. The first feature is the use of a single group of participants (i.e., a one-group design). This feature denotes that all participants are part of a single condition—meaning all participants are given the same treatments and assessments. The second feature is a linear ordering that requires the assessment of a dependent variable before and after a treatment is implemented (i.e., a pretest–posttest design). Within pretest–posttest research designs, the effect of a treatment is determined by calculating the difference between the first assessment of the dependent variable (i.e., the pretest) and the second assessment of the dependent variable (i.e., the posttest). The one-group pretest–posttest research design is illustrated in Figure 1 . This entry discusses the design’s implementation in social sciences, examines threats to internal validity, and explains when and how to use the design.

Implementation in Social Sciences

The one-group pretest–posttest research design is mostly implemented by social scientists to evaluate the effectiveness of educational programs, the restructuring of social groups and organizations, or the implementation of behavioral interventions. A common example is curriculum or instructor assessments, as instructors frequently use the one-group pretest–posttest research design to assess their own effectiveness as instructors or the effectiveness of a given curriculum. To achieve this aim, instructors assess their students’ knowledge of a given topic or skill at performing a particular behavior at the beginning of the course (i.e., a pretest, O 1 ). Then, these instructors devote their efforts over a period of time to teaching their students and assisting them in acquiring knowledge or skills that relate to the topic of the course (i.e., a treatment, X 1 ). Finally, at the conclusion of the course, instructors again assess students’ knowledge or skills via exams, projects, performances, or exit interviews (i.e., a posttest, O 2 ). The difference between students’ knowledge or skills at the beginning of the course compared with the end of the course is often attributed to the education they were provided by the instructor. This scenario is commonly used within STEM disciplines (i.e., science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), but it is also utilized within the discipline of communication studies—especially within public speaking or introductory communication courses. This example will be referenced in the subsequent section to illustrate potential threats to the internal validity of the one-group pretest–posttest research design.

Threats to Internal Validity

The one-group pretest–posttest research design does not account for many confounding variables that may threaten the internal validity of a study. In particular, this research design is susceptible to seven distinct threats to internal validity that may promote inaccurate conclusions regarding the effectiveness of a treatment or intervention.

History Effects

The first type of threat is history effects , which acknowledges that events or experiences outside the scope of a study may influence the changes in a dependent variable from pretest to posttest. The longer a research design takes to execute and the more time participants spend outside the controlled environment of an experiment or study, the greater the chance that the posttest can be influenced by unaccounted for variables or experiences. For instance, in the aforementioned example, students will spend a majority of their time outside of the confines of the classroom. As such, the growth in their knowledge or skills may be explained by experiences besides the few hours of instruction they receive per week (e.g., they could learn in other classes, watch documentaries on their own time, or refine their skills as part of extracurricular experiences).

Maturation Effect

The second threat is a maturation effect , which recognizes that any changes in the dependent variable between the pretest and posttest may be attributed to changes that naturally occur within a sample. For instance, students’ abilities to acquire knowledge over a period of time may be attributed to the development of their brain and cognitive capabilities as they age. Similar to history effects, the longer a study occurs, the more likely a maturation effect is to occur.

Figure 1 A Visual Representation of a One-Group Pretest–Posttest Research Design

Hawthorne Effect

The third type of threat is the Hawthorne effect , which acknowledges the possibility that participants’ awareness of being included in a study may influence their behavior. This effect can be problematic within a one-group pretest–posttest design if participants are not aware of their inclusion in a study until after they complete the pretest. For instance, if students are unaware of their inclusion in a study until after the pretest, they may put forth extra effort during the posttest because they are now cognizant that their performance will be evaluated and will be considered a representation of their instructors’ effectiveness (i.e., information they did not possess during the pretest).

Participant Mortality

The fourth threat is participant mortality , which occurs when a considerable number of participants withdraw from a study before completing the posttest. Throughout most research designs, it is inevitable that some participants will not finish, but when mortality becomes excessive, it can alter the relationship between the pretest and posttest assessments. For instance, if the students with the lowest scores on the pretest withdraw from the course before the posttest (i.e., midsemester)—assuming those students were less academically inclined—the posttest scores for the course will be artificially inflated. Furthermore, the examination of only the remaining students’ performances from the pretest to posttest will become more susceptible to regression threats (discussed later in this entry), and may lead to the conclusion that the treatment or invention had a detrimental effect on the dependent variable.

Instrument Reactivity

The fifth threat is instrument reactivity , which occurs when the implementation of the pretest uniquely influences participants’ performances on the posttest. Pretests can prime participants to respond to the posttest in a manner that they otherwise would not have if they did not receive the pretest. For example, the pretest of students’ knowledge at the beginning of the course could raise their awareness to particular topics or skills that they do not yet possess. This awareness would guide how they approach the course (e.g., the information they notice or how they study). Thus, the priming that resulted from the pretest would influence students’ performances on the posttest.

Instrumentation Effect

The sixth threat is an instrumentation effect , which recognizes that changes in how the dependent variable is assessed during the pretest and posttest, rather than the treatment or intervention, may explain observed changes in a dependent variable. A dependent variable is often operationalized with different assessments from the pretest to posttest to avoid instrument reactivity. For instance, when assessing students’ learning, it would not make sense to give the same exact assessment as the pretest and posttest because students would know the answers during the posttest. Thus, a new assessment is needed. The difference in the questions used within the first and second assessment may account for students’ performance.

Regression to the Mean

The final threat is regression to the mean , which recognizes that participants with extremely high or low scores on the pretest are more likely to record a score that is closer to the study average on their posttest. For instance, if a student gets a 100% on the pretest, it will be difficult for that student to record another 100% on the posttest, as a single error would lower their score. Similarly, if a student performs extremely poorly and records a 10% on the pretest, the chances are their score will increase on the posttest.

When and How to Use

Although the one-group pretest–posttest research design is recognized as a weak experimental design, under particular conditions, it can be useful. An advantage of this research design is that it is simple to implement and the results can often be calculated with simple analyses (i.e., most often a dependent t -test). Therefore, this research design is viable for students or early-career social scientists who are still learning research methods and analyses. This design is also beneficial when only one group of participants is available to the researcher or when creating a control group is unethical. In this scenario, a one-group pretest–posttest design is more rigorous than some other one-group designs (e.g., one-group posttest design) because it provides a baseline for participant performance. However, when using this research design, researchers should attempt to avoid lengthy studies and to control for confounding variables given the previously mentioned threats to internal validity.

Gregory A. Cranmer

See also Errors of Measurement ; Errors of Measurement: Regression Towards the Mean ; Internal Validity ; Mortality in Sample ; t -Test

Further Readings

Campbell, D. T. (1957). Factors relevant to the validity of experiments in social settings. Psychological Bulletin, 54 , 297–312.

Dimitrov, D. M., & Rumrill, P. D. (2003). Pretest-posttest designs and measurement of change. Work, 20 , 159–165.

Spector, P. E. (1981). Research designs . Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- One-Tailed Test

- Authoring: Telling a Research Story

- Body Image and Eating Disorders

- Hypothesis Formulation

- Methodology, Selection of

- Program Assessment

- Research Ideas, Sources of

- Research Project, Planning of

- Research Question Formulation

- Research Topic, Definition of

- Research, Inspiration for

- Social Media: Blogs, Microblogs, and Twitter

- Testability

- Acknowledging the Contribution of Others

- Activism and Social Justice

- Anonymous Source of Data

- Authorship Bias

- Authorship Credit

- Confidentiality and Anonymity of Participants

- Conflict of Interest in Research

- Controversial Experiments

- Copyright Issues in Research

- Cultural Sensitivity in Research

- Data Security

- Debriefing of Participants

- Deception in Research

- Ethical Issues, International Research

- Ethics Codes and Guidelines

- Fraudulent and Misleading Data

- Funding Research

- Health Care Disparities

- Human Subjects, Treatment of

- Informed Consent

- Institutional Review Board

- Organizational Ethics

- Peer Review

- Plagiarism, Self-

- Privacy of Information

- Privacy of Participants

- Public Behavior, Recording of

- Reliability, Unitizing

- Research Ethics and Social Values

- Researcher-Participant Relationships

- Social Implications of Research

- Archive Searching for Research

- Bibliographic Research

- Databases, Academic

- Foundation and Government Research Collections

- Library Research

- Literature Review, The

- Literature Reviews, Foundational

- Literature Reviews, Resources for

- Literature Reviews, Strategies for

- Literature Sources, Skeptical and Critical Stance Toward

- Literature, Determining Quality of

- Literature, Determining Relevance of

- Meta-Analysis

- Publications, Scholarly

- Search Engines for Literature Search

- Vote Counting Literature Review Methods

- Abstract or Executive Summary

- Academic Journals

- Alternative Conference Presentation Formats

- American Psychological Association (APA) Style

- Archiving Data

- Blogs and Research

- Chicago Style

- Citations to Research

- Evidence-Based Policy Making

- Invited Publication

- Limitations of Research

- Modern Language Association (MLA) Style

- Narrative Literature Review

- New Media Analysis

- News Media, Writing for

- Panel Presentations and Discussion

- Pay to Review and/or Publish

- Peer Reviewed Publication

- Poster Presentation of Research

- Primary Data Analysis

- Publication Style Guides

- Publication, Politics of

- Publications, Open-Access

- Publishing a Book

- Publishing a Journal Article

- Research Report, Organization of

- Research Reports, Objective

- Research Reports, Subjective

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Secondary Data

- Submission of Research to a Convention

- Submission of Research to a Journal

- Title of Manuscript, Selection of

- Visual Images as Data Within Qualitative Research

- Writer’s Block

- Writing a Discussion Section

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing a Methods Section

- Writing a Results Section

- Writing Process, The

- Coding of Data

- Content Analysis, Definition of

- Content Analysis, Process of

- Content Analysis: Advantages and Disadvantages

- Conversation Analysis

- Critical Analysis

- Discourse Analysis

- Interaction Analysis, Quantitative

- Intercoder Reliability

- Intercoder Reliability Coefficients, Comparison of

- Intercoder Reliability Standards: Reproducibility

- Intercoder Reliability Standards: Stability

- Intercoder Reliability Techniques: Cohen’s Kappa

- Intercoder Reliability Techniques: Fleiss System

- Intercoder Reliability Techniques: Holsti Method

- Intercoder Reliability Techniques: Krippendorf Alpha

- Intercoder Reliability Techniques: Percent Agreement

- Intercoder Reliability Techniques: Scott’s Pi

- Metrics for Analysis, Selection of

- Narrative Analysis

- Observational Research Methods

- Observational Research, Advantages and Disadvantages

- Observer Reliability

- Rhetorical and Dramatism Analysis

- Unobtrusive Analysis

- Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR)

- Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC)

- Internet as Cultural Context

- Internet Research and Ethical Decision Making

- Internet Research, Privacy of Participants

- Online and Offline Data, Comparison of

- Online Communities

- Online Data, Collection and Interpretation of

- Online Data, Documentation of

- Online Data, Hacking of

- Online Interviews

- Online Social Worlds

- Social Networks, Online

- Correspondence Analysis

- Cutoff Scores

- Data Cleaning

- Data Reduction

- Data Trimming

- Facial Affect Coding System

- Factor Analysis

- Factor Analysis-Oblique Rotation

- Factor Analysis: Confirmatory

- Factor Analysis: Evolutionary

- Factor Analysis: Exploratory

- Factor Analysis: Internal Consistency

- Factor Analysis: Parallelism Test

- Factor Analysis: Rotated Matrix

- Factor Analysis: Varimax Rotation

- Implicit Measures

- Measurement Levels

- Measurement Levels, Interval

- Measurement Levels, Nominal/Categorical

- Measurement Levels, Ordinal

- Measurement Levels, Ratio

- Observational Measurement: Face Features

- Observational Measurement: Proxemics and Touch

- Observational Measurement: Vocal Qualities

- Organizational Identification

- Outlier Analysis

- Physiological Measurement

- Physiological Measurement: Blood Pressure

- Physiological Measurement: Genital Blood Volume

- Physiological Measurement: Heart Rate

- Physiological Measurement: Pupillary Response

- Physiological Measurement: Skin Conductance

- Reaction Time

- Reliability of Measurement

- Reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha

- Reliability, Knuder-Richardson

- Reliability, Split-half

- Scales, Forced Choice

- Scales, Likert Statement

- Scales, Open-Ended

- Scales, Rank Order

- Scales, Semantic Differential

- Scales, True/False

- Scaling, Guttman

- Standard Score

- Time Series Notation

- Validity, Concurrent

- Validity, Construct

- Validity, Face and Content

- Validity, Halo Effect

- Validity, Measurement of

- Validity, Predictive

- Variables, Conceptualization

- Variables, Operationalization

- Z Transformation

- Confederates

- Generalization

- Imagined Interactions

- Interviewees

- Matched Groups

- Matched Individuals

- Random Assignment of Participants

- Respondents

- Response Style

- Treatment Groups

- Vulnerable Groups

- Experience Sampling Method

- Sample Versus Population

- Sampling Decisions

- Sampling Frames

- Sampling, Internet

- Sampling, Methodological Issues in

- Sampling, Multistage

- Sampling, Nonprobability

- Sampling, Probability

- Sampling, Special Population

- Opinion Polling

- Sampling, Random

- Survey Instructions

- Survey Questions, Writing and Phrasing of

- Survey Response Rates

- Survey Wording

- Survey: Contrast Questions

- Survey: Demographic Questions

- Survey: Dichotomous Questions

- Survey: Filter Questions

- Survey: Follow-up Questions

- Survey: Leading Questions

- Survey: Multiple-Choice Questions

- Survey: Negative-Wording Questions

- Survey: Open-Ended Questions

- Survey: Questionnaire

- Survey: Sampling Issues

- Survey: Structural Questions

- Surveys, Advantages and Disadvantages of

- Surveys, Using Others’

- Under-represented Group

- Alternative News Media

- Analytic Induction

- Archival Analysis

- Artifact Selection

- Autoethnography

- Axial Coding

- Burkean Analysis

- Close Reading

- Coding, Fixed

- Coding, Flexible

- Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS)

- Covert Observation

- Critical Ethnography

- Critical Incident Method

- Critical Race Theory

- Cultural Studies and Communication

- Demand Characteristics

- Ethnographic Interview

- Ethnography

- Ethnomethodology

- Fantasy Theme Analysis

- Feminist Analysis

- Field Notes

- First Wave Feminism

- Fisher Narrative Paradigm

- Focus Groups

- Frame Analysis

- Garfinkling

- Gender-Specific Language

- Grounded Theory

- Hermeneutics

- Historical Analysis

- Informant Interview

- Interaction Analysis, Qualitative

- Interpretative Research

- Interviews for Data Gathering

- Interviews, Recording and Transcribing

- Marxist Analysis

- Meta-ethnography

- Metaphor Analysis

- Narrative Interviewing

- Naturalistic Observation

- Negative Case Analysis

- Neo-Aristotelian Method

- New Media and Participant Observation

- Participant Observer

- Pentadic Analysis

- Performance Research

- Phenomenological Traditions

- Poetic Analysis

- Postcolonial Analysis

- Power in Language

- Pronomial Use-Solidarity

- Psychoanalytic Approaches to Rhetoric

- Public Memory

- Qualitative Data

- Queer Methods

- Queer Theory

- Researcher-Participant Relationships in Observational Research

- Respondent Interviews

- Rhetoric as Epistemic

- Rhetoric, Aristotle’s: Ethos

- Rhetoric, Aristotle’s: Logos

- Rhetoric, Aristotle’s: Pathos

- Rhetoric, Isocrates’

- Rhetorical Artifact

- Rhetorical Method

- Rhetorical Theory

- Second Wave Feminism

- Snowball Subject Recruitment

- Social Constructionism

- Social Network Analysis

- Spontaneous Decision Making

- Symbolic Interactionism

- Terministic Screens

- Textual Analysis

- Thematic Analysis

- Theoretical Traditions

- Third-Wave Feminism

- Transcription Systems

- Triangulation

- Turning Point Analysis

- Unobtrusive Measurement

- Visual Materials, Analysis of

- t -Test, Independent Samples

- t -Test, One Sample

- t -Test, Paired Samples

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Analysis of Ranks

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

- Bonferroni Correction

- Decomposing Sums of Squares

- Eta Squared

- Factorial Analysis of Variance

- McNemar Test

- One-Way Analysis of Variance

- Post Hoc Tests

- Post Hoc Tests: Duncan Multiple Range Test

- Post Hoc Tests: Least Significant Difference

- Post Hoc Tests: Scheffe Test

- Post Hoc Tests: Student-Newman-Keuls Test

- Post Hoc Tests: Tukey Honestly Significance Difference Test

- Repeated Measures

- Between-Subjects Design

- Blocking Variable

- Control Groups

- Counterbalancing

- Cross-Sectional Design

- Degrees of Freedom

- Delayed Measurement

- Ex Post Facto Designs

- Experimental Manipulation

- Experiments and Experimental Design

- External Validity

- Extraneous Variables, Control of

- Factor, Crossed

- Factor, Fixed

- Factor, Nested

- Factor, Random

- Factorial Designs

- False Negative

- False Positive

- Field Experiments

- Hierarchical Model

- Individual Difference

- Internal Validity

- Laboratory Experiments

- Latin Square Design

- Longitudinal Design

- Manipulation Check

- Measures of Variability

- Median Split of Sample

- Mixed Level Design

- Multitrial Design

- Null Hypothesis

- Orthogonality

- Overidentified Model

- Pilot Study

- Population/Sample

- Power Curves

- Quantitative Research, Purpose of

- Quantitative Research, Steps for

- Quasi-Experimental Design

- Random Assignment

- Replication

- Research Proposal

- Sampling Theory

- Sampling, Determining Size

- Solomon Four-Group Design

- Stimulus Pre-test

- Two-Group Pretest–Posttest Design

- Two-Group Random Assignment Pretest–Posttest Design

- Variables, Control

- Variables, Dependent

- Variables, Independent

- Variables, Latent

- Variables, Marker

- Variables, Mediating Types

- Variables, Moderating Types

- Within-Subjects Design

- Analysis of Residuals

- Bivariate Statistics

- Bootstrapping

- Confidence Interval

- Conjoint Analysis

- Contrast Analysis

- Correlation, Pearson

- Correlation, Point-Biserial

- Correlation, Spearman

- Covariance/Variance Matrix

- Cramér’s V

- Discriminant Analysis

- Kendall’s Tau

- Kruskal-Wallis Test

- Linear Regression

- Linear Versus Nonlinear Relationships

- Multicollinearity

- Multiple Regression

- Multiple Regression: Block Analysis

- Multiple Regression: Covariates in Multiple Regression

- Multiple Regression: Multiple R

- Multiple Regression: Standardized Regression Coefficient

- Partial Correlation

- Phi Coefficient

- Semi-Partial r

- Simple Bivariate Correlation

- Categorization

- Cluster Analysis

- Data Transformation

- Errors of Measurement

- Errors of Measurement: Attenuation

- Errors of Measurement: Ceiling and Floor Effects

- Errors of Measurement: Dichotomization of a Continuous Variable

- Errors of Measurement: Range Restriction

- Errors of Measurement: Regression Toward the Mean

- Frequency Distributions

- Heterogeneity of Variance

- Heteroskedasticity

- Homogeneity of Variance

- Hypothesis Testing, Logic of

- Intraclass Correlation

- Mean, Arithmetic

- Mean, Geometric

- Mean, Harmonic

- Measures of Central Tendency

- Mortality in Sample

- Normal Curve Distribution

- Relationships Between Variables

- Sensitivity Analysis

- Significance Test

- Simple Descriptive Statistics

- Standard Deviation and Variance

- Standard Error

- Standard Error, Mean

- Statistical Power Analysis

- Type I error

- Type II error

- Univariate Statistics

- Variables, Categorical

- Variables, Continuous

- Variables, Defining

- Variables, Interaction of

- Autoregressive, Integrative, Moving Average (ARIMA) Models

- Binomial Effect Size Display

- Cloze Procedure

- Cross Validation

- Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis

- Curvilinear Relationship

- Effect Sizes

- Hierarchical Linear Modeling

- Lag Sequential Analysis

- Log-Linear Analysis

- Logistic Analysis

- Margin of Error

- Markov Analysis

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation

- Meta-Analysis: Estimation of Average Effect

- Meta-Analysis: Fixed Effects Analysis

- Meta-Analysis: Literature Search Issues

- Meta-Analysis: Model Testing

- Meta-Analysis: Random Effects Analysis

- Meta-Analysis: Statistical Conversion to Common Metric

- Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA)

- Multivariate Statistics

- Ordinary Least Squares

- Path Analysis

- Probit Analysis

- Structural Equation Modeling

- Time-Series Analysis

- Acculturation

- African American Communication and Culture

- Agenda Setting

- Applied Communication

- Argumentation Theory

- Asian/Pacific American Communication Studies

- Bad News, Communication of

- Basic Course in Communication

- Business Communication

- Communication and Aging Research

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Evolution

- Communication and Future Studies

- Communication and Human Biology

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Apprehension

- Communication Assessment

- Communication Competence

- Communication Education

- Communication Ethics

- Communication History

- Communication Privacy Management Theory

- Communication Skills

- Communication Theory

- Conflict, Mediation, and Negotiation

- Corporate Communication

- Crisis Communication

- Cross-Cultural Communication

- Cyberchondria

- Dark Side of Communication

- Debate and Forensics

- Development of Communication in Children

- Digital Media and Race

- Digital Natives

- Dime Dating

- Disability and Communication

- Distance Learning

- Educational Technology

- Emergency Communication

- Empathic Listening

- English as a Second Language

- Environmental Communication

- Family Communication

- Feminist Communication Studies

- Film Studies

- Financial Communication

- Freedom of Expression

- Game Studies

- Gender and Communication

- GLBT Communication Studies

- GLBT Social Media

- Group Communication

- Health Communication

- Health Literacy

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Instructional Communication

- Intercultural Communication

- Intergenerational Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International Communication

- International Film

- Interpersonal Communication

- Intrapersonal Communication

- Language and Social Interaction

- Latino Communication

- Legal Communication

- Managerial Communication

- Mass Communication

- Massive Multiplayer Online Games

- Massive Open Online Courses

- Media and Technology Studies

- Media Diffusion

- Media Effects Research

- Media Literacy

- Message Production

- Multiplatform Journalism

- Native American or Indigenous Peoples Communication

- Nonverbal Communication

- Organizational Communication

- Parasocial Communication

- Patient-Centered Communication

- Peace Studies

- Performance Studies

- Personal Relationship Studies

- Philosophy of Communication

- Political Communication

- Political Debates

- Political Economy of Media

- Popular Communication

- Pornography and Research

- Public Address

- Public Relations

- Reality Television

- Relational Dialectics Theory

- Religious Communication

- Rhetorical Genre

- Risk Communication

- Robotic Communication

- Science Communication

- Selective Exposure

- Service Learning

- Small Group Communication

- Social Cognition

- Social Network Systems

- Social Presence

- Social Relationships

- Spirituality and Communication

- Sports Communication

- Strategic Communication

- Structuration Theory

- Training and Development in Organizations

- Video Games

- Visual Communication Studies

- Wartime Communication

- Academic Journal Structure

- Citation Analyses

- Communication Journals

- Interdisciplinary Journals

- Professional Communication Organizations (NCA, ICA, Central, etc.)

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

IMAGES

COMMENTS

One-Group Posttest Only Design. In a one-group posttest only design, ... This is the weakest type of quasi-experimental design. A major limitation to this design is the lack of a control or comparison group. There is no way to determine what the attitudes of these students would have been if they hadn't completed the anti-drug program.

One-Group Posttest Only Design. In a one-group posttest only design, a treatment is implemented (or an independent variable is manipulated) and then a dependent variable is measured once after the treatment is implemented. Imagine, for example, a researcher who is interested in the effectiveness of an anti-drug education program on elementary school students' attitudes toward illegal drugs.

A matched pairs design is an experimental design where pairs of participants are matched in terms of key variables, such as age or socioeconomic status. One member of each pair is then placed into the experimental group and the other member into the control group.

The simplest true experimental designs are two group designs involving one treatment group and one control group, and are ideally suited for testing the effects of a single independent variable that can be manipulated as a treatment. The two basic two-group designs are the pretest-posttest control group design and the posttest-only control

One-Group Posttest-Only Design The type of quasi-experiment most susceptible to threats to internal validity is the one-group posttest-only design, which is also called the one-shot case study (Campbell & Stanley, 1966). Using the one-group posttest-only design, a researcher measures a dependent variable for one group of participants following

The one-group posttest-only design (a.k.a. one-shot case study) is a type of quasi-experiment in which the outcome of interest is measured only once after exposing a non-random group of participants to a certain intervention.. The objective is to evaluate the effect of that intervention which can be: A training program; A policy change; A medical treatment, etc.

The one-group pretest-posttest design is a useful experimental setup for assessing an intervention's impact on a single group. Its simplicity and cost-effectiveness make it valuable for exploratory research, pilot studies, and situations where resources for a control group are limited.

The one-group pretest-posttest research design does not account for many confounding variables that may threaten the internal validity of a study. In particular, this research design is susceptible to seven distinct threats to internal validity that may promote inaccurate conclusions regarding the effectiveness of a treatment or intervention.

Posttest-Only Control Group Design: Measures only the outcome after an intervention, with both experimental and control groups. Example: Two groups are observed after one group receives a treatment, and the other receives no intervention. 3. Quasi-Experimental Designs

Threats to the causal validity of the single group pre- and post-test design A number of threats to the single group design weaken a causal interpretation. Some of these, such as attrition or un-blinded assessment, are common to experi-mental or multiple group designs and we will not discuss them further (Cook & Campbell, 1979). Others, however ...