Stress: A Case Study

Read the story of a women who thought she was having a heart attack, but was instead diagnosed with panic disorder, panic attacks.

Although on the surface everything seemed fine, she felt that, "the wheels on my tricycle are about to fall off. I'm a mess." Over the past several months she had attacks of shortness of breath, heart palpitations, chest pains, dizziness, and tingling sensations in her fingers and toes. Filled with a sense of impending doom, she would become anxious to the point of panic. Every day she awoke with a dreaded feeling that an attack might strike without reason or warning.

On two occasions, she rushed to a nearby hospital emergency room fearing she was having a heart attack. The first episode followed an argument with her boyfriend about the future of their relationship. After studying her electrocardiogram, the emergency room doctor told her she was "just hyperventilating" and showed her how to breathe into a paper bag to handle the situation in the future. She felt foolish and went home embarrassed, angry and confused. She remained convinced that she had almost had a heart attack.

Her next severe attack occurred after a fight at work with her boss over a new marketing campaign. This time she insisted that she be hospitalized overnight for extensive diagnostic tests and that her internist be consulted. The results were the same--no heart attack. Her internist prescribed a tranquilizer to calm her down.

Convinced now that her own doctor was wrong, she sought the advice of a cardiologist, who conducted another battery of tests, again with no physical findings. The doctor concluded that stress was the primary cause of the panic attacks and "heart attack" symptoms. The doctor referred her to psychologist specializing in stress.

During her first visit, professionals administered stress tests and explained how stress could cause her physical symptoms. At her next visit, utilizing the tests results, they described to her the sources and nature of her health problems. The tests revealed that she was highly susceptible to stress, that she was enduring enormous stress from her family, her personal life, and her job, and that she was experiencing a number of stress-related symptoms in her emotional, sympathetic nervous, muscular and endocrine systems. She wasn't sleeping or eating well, didn't exercise, abused caffeine and alcohol, and lived on the edge financially.

The stress testing crystallized how susceptible she was to stress, what was causing her stress, and how stress was expressing itself in her "heart attack" and other symptoms. This newly found knowledge eliminated a lot of her confusion and separated her concerns into simpler, more manageable problems.

She realized that she was feeling tremendous pressure from her boyfriend, as well as her mother to settle down and get married; yet, she didn't feel ready. At the same time, work was overwhelming her as a new marketing campaign began. Any serious emotional incident--a quarrel with her boyfriend or her boss--sent her over the edge. Her body's response was hyperventilation, palpitations, chest pain, dizziness, anxiety, and a dreadful sense of doom. Stress, in short, was destroying her life.

Adapted from The Stress Solution by Lyle H. Miller, Ph.D., and Alma Dell Smith, Ph.D.

next: Terrorism Fear: What You Can Do To Alleviate It ~ anxiety-panic library articles ~ all anxiety disorders articles

APA Reference Staff, H. (2007, February 18). Stress: A Case Study, HealthyPlace. Retrieved on 2024, December 23 from https://www.healthyplace.com/anxiety-panic/articles/stress-a-case-study

Medically reviewed by Harry Croft, MD

Related Articles

Anxiety and Panic Attack Articles

The different kinds of stress, anxiety, panic, phobia, ocd conference transcripts table of contents, marijuana use - the cause, do i have anxiety, self-help stress management, the biochemistry of panic.

2024 HealthyPlace Inc. All Rights Reserved. Site last updated December 23, 2024

- Free Case Studies

- Business Essays

Write My Case Study

Buy Case Study

Case Study Help

- Case Study For Sale

- Case Study Services

- Hire Writer

Case Study on Acute Stress Disorder

Acute stress disorder case study:.

Acute stress disorder is the state of the strong anxiety and other symptoms which occur after a shocking accident which has affected the victim’s psychics negatively. the brightest examples of acute stress disorder occur after the tragic experience faced by an individual who has witnessed a car accident, air crash, the fire, the death of a great number of people or a close person. The person experiences the symptoms of the disorder during the first month after the tragic event and they are associated with anxiety, numbing, dissociative amnesia, etc. Amnesia is quite a common symptom after the strong shock, because the human mind wants to get rid of the stressing image of the irritant which causes harm to the human psychics. The irritant is forgotten and the person does not remember what has caused her chronic stress and constant anxiety.

The negative side of the acute stress disorder is the risk of the development of the disorder into something more serious, for example, posttraumatic stress disorder. Most often the disorder does not last long. It is possible that the person will suffer from the shock from two days to four weeks and the disorder disappears without the third person’s help. Of course, if the patient is not able to cope with the problem himself, he is able to apply for help of the professional psychologist who would treat acute stress disorder with the help of the cognitive therapy, relaxations and personal conversations with the patient in order to reduce stress.Acute stress disorder is a serious problem which can be observed by the student who is interested in psychology and especially the psychological disorders.

We Will Write a Custom Case Study Specifically For You For Only $13.90/page!

The young person is able to analyze the issue from all sides learning about the general meaning of acute stress disorder, its symptoms, methods of treatment, its danger for the human health, etc. In order to succeed in writing, the student is supposed to study the case effectively, interview or read about the patient, his case, the history of his disease and find out about the cause of the stress and its effect on the patient’s psychics. The student is expected to dwell on the solution of the problem, because a case study is not a simple observation but the solution of the problem on the disorder.The young professional is able to impress the teacher with the help of the advice borrowed from a free example case study on acute stress disorder written online. It is smart to look through a well-formatted and logically-arranged free sample case study on acute stress disorder composed by the experienced writer for the student’s convenience.

Related posts:

- Case Study on Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Case Study on Teenage Stress

- Case Study on Bipolar Disorder

- Case Study on Panic Disorder

- Pneumonia is an acute respiratory infection

Quick Links

Privacy Policy

Terms and Conditions

Testimonials

Our Services

Case Study Writing Services

Case Studies For Sale

Our Company

Welcome to the world of case studies that can bring you high grades! Here, at ACaseStudy.com, we deliver professionally written papers, and the best grades for you from your professors are guaranteed!

[email protected] 804-506-0782 350 5th Ave, New York, NY 10118, USA

Acasestudy.com © 2007-2019 All rights reserved.

Hi! I'm Anna

Would you like to get a custom case study? How about receiving a customized one?

Haven't Found The Case Study You Want?

For Only $13.90/page

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Acute Stress Symptoms in Children: Results From an International Data Archive

Dr nancy kassam-adams , phd, dr patrick a palmieri , phd, dr kristine rork , phd, dr douglas l delahanty , phd, dr justin kenardy , phd, ms kristen l kohser , msw, dr markus a landolt , phd, dr robyne le brocque , phd, dr meghan l marsac , phd, dr richard meiser-stedman , phd, dr reginald d v nixon , phd, dr eric bui , md, phd, ms caitlin mcgrath , bpsych.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to Nancy Kassam-Adams, PhD, Center for Injury Research and Prevention, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3535 Market Street, Suite 1150, Philadelphia PA 19104; [email protected]

Issue date 2012 Aug.

To describe the prevalence of acute stress disorder (ASD) symptoms and examine proposed DSM-5 symptom criteria in relation to concurrent functional impairment in children.

From an international archive, datasets were identified which included assessment of acute traumatic stress reactions and concurrent impairment in children age 5 to 17. Data came from 15 studies conducted in the US, UK, Australia, and Switzerland with 1645 children. Dichotomized items were created to indicate the presence or absence of each of the 14 proposed ASD symptoms and functional impairment. The performance of a proposed diagnostic criterion (number of ASD symptoms required) was examined as a predictor of concurrent impairment.

Each ASD symptom was endorsed by 14% to 51% of children; 41% reported clinically-relevant impairment. Children reported from 0 to 13 symptoms (mean = 3.6). Individual ASD symptoms were associated with greater likelihood of functional impairment. The DSM-5 proposed 8-symptom requirement was met by 202 (12.3%) children, and had low sensitivity (.25) in predicting concurrent clinically-relevant impairment. Requiring fewer symptoms (three to four) greatly improved sensitivity while maintaining moderate specificity.

Conclusions

This group of symptoms appears to capture aspects of traumatic stress reactions that can create distress and interfere with children’s ability to function in the acute post-trauma phase. Results provide a benchmark for comparison with adult samples; a smaller proportion of children met the 8-symptom criterion than reported for adults. Symptom requirements for the ASD diagnosis may need to be lowered to optimally identify children whose acute distress warrants clinical attention.

Keywords: acute stress disorder, DSM-5 , diagnostic criteria

Introduction

Assessment of acute traumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents poses both practical and conceptual challenges. On a practical level, children who have recently experienced a potentially traumatic event rarely present for formal mental health services, and thus assessment to discern who is in need of clinical attention may best be accomplished in other settings (health care settings, schools, post-disaster community settings). Empirically sound self-report 1 and interview 2 measures of child acute traumatic stress are a relatively recent development, and these measures require additional validation in a range of populations. In the aftermath of trauma it can be challenging to distinguish acute distress in children which will resolve (with time and family support) from acute distress which will persist or worsen without clinical attention and intervention. Improving the conceptual basis for assessment and ensuring that diagnosis of acute traumatic stress in children appropriately identifies those in need of assistance are thus key challenges for the field.

The stated goal of the workgroup developing proposed DSM-5 criteria for acute stress disorder (ASD) is to set criteria that will capture a severity of acute stress reactions within the first month that warrants clinical attention. 3 The workgroup also aims to set diagnostic criteria that will identify a minority of trauma-exposed persons, arguing that if the majority of those exposed to trauma are diagnosed with ASD, they have not succeeded in identifying those most at need. 3 There are two substantivel changes in the proposed conceptualization of the ASD diagnosis. First, it is intended to capture severe early distress without regard to whether these symptoms predict ongoing or persistent traumatic stress, and second, diagnostic status is determined based on an overall ASD symptom picture rather than separate symptom categories. The current proposed diagnostic criteria require that eight of 14 symptoms (of any type: including intrusion symptoms, dissociative symptoms, avoidance symptoms, and arousal symptoms) be present, and that “the disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” 3 The ASD workgroup proposed that this criterion be tested across datasets. This manuscript follows their recommendation by examining the utility of the proposed criterion in a large combined international dataset of children and adolescents.

One way to distinguish transient acute stress reactions following a traumatic event from severe symptoms that warrant clinical attention is to ascertain the likelihood that a given symptom level is associated with significant impairment. Thus, in the case of children, an optimal ‘cut-off’ for the number of symptoms required for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder would have good sensitivity and specificity with regard to identifying those with concurrent impairment in social, academic, or interpersonal functioning. It is possible that optimal diagnostic criteria for traumatic stress disorders in school-age children and adolescents may differ from those for adults. 4 – 6 Indeed, current proposed symptom criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in DSM-5 include lower symptom thresholds for children. 7 Further, prior studies suggest that children and adolescents might differ from adults with regard to the prevalence of acute traumatic stress symptoms, 8 – 9 or the association of these symptoms with concurrent or persistent impairment. 10 – 11

To understand the full range of children’s potential responses to acute traumatic events and to be able to examine the boundaries between normative responses and diagnostic-level acute stress reactions, it is important to assess both symptoms and functional impairment prospectively (because later retrospective reports may be clouded by concurrent symptom status 12 ) in samples identified based on exposure to an event rather than referral for clinical attention. The purpose of the current analyses was to utilize a newly available data archive of child traumatic stress studies to (a) describe the prevalence of each ASD symptom and the number of ASD symptoms endorsed in school-age and adolescent children assessed prospectively within one month of exposure to acute trauma, and (b) examine the proposed DSM-5 symptom count criterion (and alternative symptom counts) in relation to concurrent functional impairment in these children,

This project made use of a new and unique data resource, the PTSD after Acute Child Trauma (PACT) Data Archive. This international archive contains investigator-provided, de-identified datasets from prospective studies of children exposed to an acute potentially traumatic event. Currently, the archive contains datasets from 19 studies and from four countries. Each dataset in the archive includes basic data on demographics, trauma characteristics, one or more potential predictors of ongoing traumatic stress assessed soon after a traumatic event, and at least one measurement of traumatic stress symptoms at a later time point. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Archive’s home institution determined that the PACT Data Archive is exempt from IRB review per 45 CFR 46.101(b) #4.

For the current analyses, we identified 15 datasets in the PACT Archive which included data from children and adolescents age 5 to 17 regarding acute traumatic stress symptoms and concurrent impairment two days to one month after an acute potentially traumatic event. These datasets represent studies conducted in four countries (US, UK, Australia, and Switzerland) with 1645 children. Table 1 shows sample characteristics and measures of acute traumatic stress and impairment in datasets included in the current analyses. In each study, children were recruited for participation based on their exposure to a potentially traumatic event (i.e. non-clinical samples)

Study characteristics: Datasets included in analyses

Note: ADIS = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; ASC-Kids = Acute Stress Checklist for Children; CAPS-CA = Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Scale for Children and Adolescents; CASQ = Child Acute Stress Questionnaire; CPSS = Child PTSD Symptom Scale; CRIES = Children’s Impact of Event Scale; CTSQ = Child Traumatic Stress Questionnaire; IBS-A-KJ = Interview zu Akute Belastungsstörungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen; ISRC = Immediate Stress Reaction Questionnaire; TSCC = Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children

Kassam-Adams, N. and Gold, J. Unpublished data, 2011.

Kassam-Adams, N. and Winston, F. Unpublished data, 2006.

Fein J. Unpublished data, 2003.

Measure used to assess impairment in this study

The original studies from which these data were drawn used a range of different measures to assess acute traumatic stress symptoms and impairment, including both questionnaire and interview measures (see Table 1 .) In order to combine data on specific acute traumatic stress symptoms (at the item level) across studies, we first identified candidate congruent items from each available measure within the dataset. For each DSM-5 ASD symptom, the core group of investigators in the PACT Project Group (N.K.A., P.P., J.K., D.D., R.L., R.N., R.M.S.) then reviewed available items and arrived at consensus regarding the combination of items for analysis. This expert group determined a) that each candidate item adequately represented the specific symptom construct (e.g. intrusive distressing memories), and b) that the candidate items from disparate measures were sufficiently congruent in wording to be combined for these analyses. Not all studies (datasets) were able to contribute to the assessment of every acute traumatic stress symptom (see Table 1 ). As one example, we identified that the proposed DSM-5 symptom of “spontaneous or cued recurrent, involuntary, intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event” had been assessed on checklist measures via items such as “I can’t stop thinking about it” (Acute Stress Checklist for Children [ASC-Kids] 1 ), “Having upsetting thoughts or images about the event that came into your head when you didn’t want them to” (Child PTSD Symptom Scale [CPSS] 26 ), “Do you think about it even when you don’t mean to?” (Children’s Impact of Event Scales [CRIES] 13 – 14 ), and on interview measures via prompts such as “Did you think about (event) even when you didn’t want to?” (Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents [CAPS-CA] 24 ), and “Do you have a lot of thoughts that you don’t want to have about (frightening event)?” (Anxiety Disorders Interview Scale [ADIS] 15 ). The expert panel found that these were sufficiently congruent to be combined (as dichotomized ratings) for analysis.

Item ratings were then dichotomized utilizing each measure’s standard scoring rules for symptom presence; if such a standard was not available, this expert group reached consensus on an appropriate cut-point in the item rating scale for presence versus absence of the symptom, comparable to those utilized for similar measures. We also created a dichotomous variable for the presence/absence of concurrent impairment, based on items available within many of the traumatic stress measures assessing impairment in social, academic, or other functioning; such as “Since this happened, getting along with friends or family is harder for me.” (ASC-Kids 1 ). These common dichotomous variables (14 symptom items and presence/absence of impairment) allowed analyses of pooled data from all 15 datasets regarding acute stress symptoms, and from nine of these datasets with regard to impairment. This approach to pooling data from existing studies is consistent with an “integrative data analysis” approach, with the potential advantages of increased sample heterogeneity and increased statistical power. 16

Data analysis

Based on the common dichotomized ASD symptom items, we created an ASD symptom count variable (number of symptoms present) with potential scores ranging from 0 to 14. To evaluate the relationship between ASD symptoms and concurrent impairment, we first examined bivariate associations between each symptom item and impairment by means of Chi square analyses. We then examined the performance of different cut-off scores (i.e. the number of ASD symptoms required) to best predict the presence of concurrent impairment. All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 20 (SPSS, Chicago IL).

Sample characteristics

Table 2 shows demographic characteristics, trauma type, and country of residence for the total combined sample across all 15 datasets. Children in this combined sample ranged in age from 5 to 17 years (mean = 11.6; SD = 3.0), about two thirds were male, and nearly half were of minority ethnicity. The most common index trauma was injury, although categories were not mutually exclusive, i.e. a child who was injured and was in a road traffic accident was counted in both categories. Mean time from the acute event to assessment of acute stress reactions was 13.1 days (SD = 8.3).

Characteristics of combined sample (n = 1645)

Prevalence of proposed DSM-5 ASD symptoms and functional impairment in children

See Table 3 for prevalence of each ASD symptom and of impairment. The most commonly reported symptoms were avoidance of thoughts, conversations, or feelings (51.4%), altered sense of reality (42.5%), and intrusive distressing memories (40.6%). Flashbacks or reliving (15.6%) and distressing dreams (13.6%) were least commonly endorsed. The number of symptoms reported by children ranged from 0 to 13 (median = 3 symptoms; mean = 3.6; SD = 3.0), with 202 (12.3%) reporting eight or more symptoms. Impairment ratings were available for a total of 1172 children, from nine of the 15 datasets. Less than half of the children reported impairment. One hundred twenty-three (10.5%) children met proposed DSM-5 ASD criteria of eight or more symptoms plus significant impairment.

Prevalence of DSM-5 acute stress disorder (ASD) symptoms and functional impairment in children in combined sample (overall n = 1645)

Association of ASD symptoms with concurrent reports of impairment in children

Individual ASD symptoms were associated with greater likelihood of concurrent impairment. For 13 of the proposed 14 DSM-5 symptoms, Chi square analyses revealed that a higher proportion of children who reported the specific symptom also reported impairment (see Table 4 ). This was true for all symptoms other than agitation (smaller sample size available for analysis may account for this non-significant finding.)

Association of each DSM-5 acute stress disorder (ASD) symptom with concurrent functional impairment (overall n = 1172)

p < .001

We examined the utility of the proposed 8-symptom requirement for ASD by assessing how well this symptom cutoff discriminated between children with and without significant acute functional impairment (see Table 5 ). Positive predictive value (PPV) was high; 75% of children with at least 8 symptoms reported impairment (compared to 36% of those with fewer than 8 symptoms). However, sensitivity was low (.25), such that only one quarter of those with acute impairment would have met criteria for an ASD diagnosis if 8 symptoms were required.

Performance of different acute stress symptom requirements in predicting concurrent ratings of impairment (n = 1172).

Note: The workgroup developing proposed DSM-5 criteria for acute stress disorder (ASD) has suggested 8 symptoms as a diagnostic criterion (in bold). NPV = Negative predictive value; PPV = Positive predictive value.

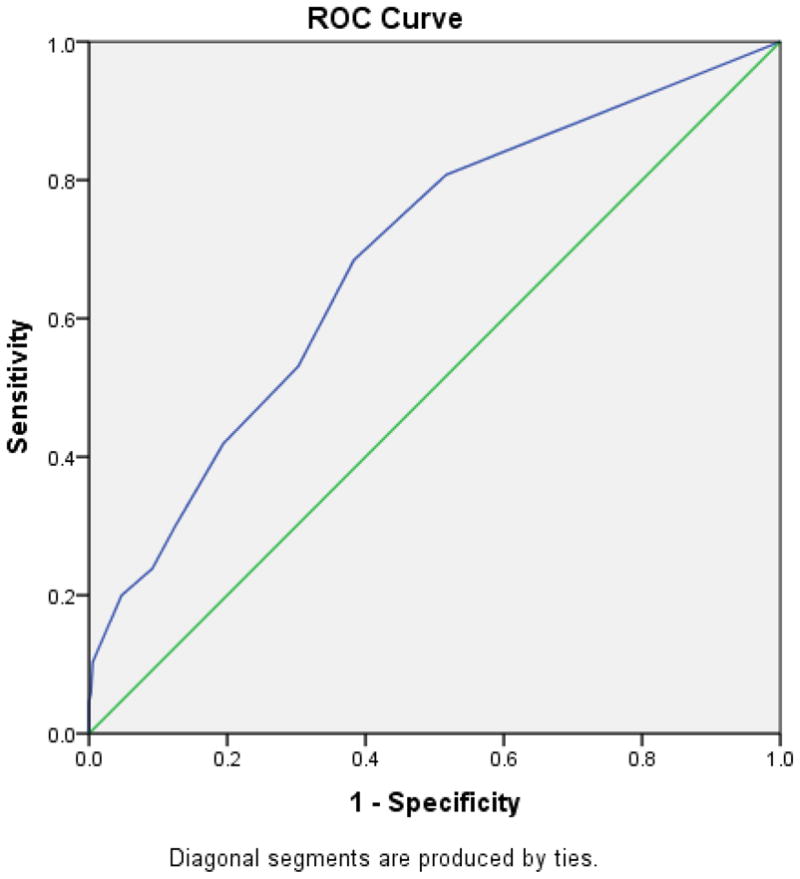

Table 5 presents sensitivity, specificity, PPV, negative predictive value (NPV), and percent correctly classified for the 8-symptom requirement and alternative symptom counts. In receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analyses of ASD symptom count as a ‘predictor’ of concurrent impairment, the area under the curve (AUC) was .70 (95% CI: .67–.73). Examining the coordinates of the ROC curve ( Figure 1 and Table 5 ) suggests that an optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity is achieved at a cutpoint of 3 or 4 symptoms. For example, a 3-symptom rule resulted in greater sensitivity than the 8-symptom rule (detecting three quarters of those with impairment), moderate specificity, and a similar proportion of children correctly classified. Compared to the 10.5% of children who had at least eight ASD symptoms and impairment, 356 (30.4%) had at least three ASD symptoms and impairment.

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve for acute stress disorder (ASD) symptom count as a predictor of the presence of concurrent functional impairment.

In exploratory analyses, we examined the performance of the 8-symptom requirement for school-age children (ages 5 to 11 years; n = 552) and for adolescents (age 12 to 17 years; n = 620) separately. For the younger group, sensitivity = .32, specificity = .92; for the older group, sensitivity = .20, specificity = .95. A 3-symptom rule resulted in improved sensitivity in both younger and older children (.79 and .69, respectively) and retained moderate sensitivity in each age group (.51 and .62, respectively)

Clear conceptualization and empirically-validated diagnostic criteria can advance efforts to identify children and youth with significant distress who need increased psychosocial supports or formal clinical attention. Data from 15 studies including 1645 children assessed soon after an acute trauma were combined to examine the utility of proposed DSM-5 ASD symptom criteria. Each symptom was endorsed by 14% to 51% of children. Thirteen of the 14 symptoms were individually associated with impairment, suggesting that this list of symptoms does capture key aspects of traumatic stress responses that can create distress and interfere with children’s ability to function in the acute post-trauma phase. These analyses provide an initial benchmark for comparison with adult samples. For example, the ASD workgroup reported that 20% of adults in three “large scale datasets” from Israel, the UK, and Australia met the 8-symptom criterion 3 . In the current large combined dataset of children and adolescents, a smaller proportion (12%) met this proposed symptom criterion.

In constructing diagnostic criteria for mental disorders, the DSM-5 development process has attempted to clarify the distinction between psychiatric symptoms and the potentially disabling consequences of those symptoms. 17 However, in the case of early emotional responses to extremely difficult events and experiences, it seems particularly relevant to consider the connection between symptoms and functional impairment in determining what constitutes a ‘disorder.’ The revised ASD diagnostic criteria aim to “facilitate treatment for those suffering significant distress and whose response suggests that this distress may be interfering sufficiently or distressing the person excessively such that treatment may facilitate recovery.” 3 Examining the current results from this perspective, the proposed 8-symptom requirement falls short for children and adolescents. Its low sensitivity means that 75% of children who reported impairment had fewer than 8 symptoms and would not have received a diagnosis of ASD. For children and adolescents, requiring fewer symptoms would better achieve the objective of identifying those with clinically relevant distress or interference with functioning. These results suggest that a lower symptom count criterion (three or four symptoms) could achieve higher sensitivity while maintaining a reasonable degree of specificity. This trade-off between specificity and sensitivity is warranted in most clinical settings, where the disadvantages of missing a positive case (i.e., a child in need of clinical attention in the acute aftermath of trauma exposure) are likely to be greater than the disadvantages of offering services to a child who does not need them. Appropriate clinical responses to acute stress disorder include brief interventions that incorporate trauma-focused cognitive behavioral approaches 18 and that shore up a child’s existing support systems by helping parents respond appropriately. 19

A limitation of this investigation is the need to use solely dichotomous values in order to combine items across different measures in the combined dataset. Another potential limitation is that when both symptoms and impairment are measured by self-report, their association may be in part an artifact of generalized subjective distress. The set of 15 studies included here reflect both the strengths and limitations of existing research studies on acute traumatic stress reactions in children. For example, the datasets included here do not include children from the developing world and thus replication with other populations is needed. We believe that these datasets represent a fairly large proportion of the existing child studies that have assessed ASD symptoms within one month of a potentially traumatic event (the authors welcome contact from investigators who have relevant datasets and would like to learn about adding these to the PACT Archive). Many of the available studies have assessed acute stress reactions after unintentional injuries or road traffic accidents. These represent highly prevalent types of acute child trauma which convey risk for both acute and persistent traumatic stress disorders 11 , 20 – 22 , and thus have substantial public health impact. Nevertheless, the field would benefit from more prospective studies that carefully assess child acute stress reactions within the first month after other types of traumatic events (e.g., disasters, interpersonal violence). It is possible that symptom criteria might vary for acute events of different types or intensities. Future research efforts should include all fourteen proposed DSM-5 ASD symptoms (and other candidate items which may be relevant for children) in order to test the utility of alternative acute stress symptom requirements as predictors of significant concurrent (and persistent) distress and impairment in children and adolescents exposed to a range of acute traumas. Although it is not the intention of the DSM-5 ASD criteria, the longitudinal association of acute traumatic stress symptoms with ongoing or persistent distress and impairment is certainly of great clinical interest and should continue to be examined in prospective studies.

These analyses represent the fruit of a new and unique data resource for child traumatic stress studies, the PACT Data Archive, which allowed us to combine individual-level data from 15 studies to examine children’s acute traumatic stress reactions. Increasingly, national research funding agencies are encouraging or requiring that data generated from publicly funded research be archived or made available to other investigators beyond the life of the original investigation. 23 – 25 The current analyses demonstrate the potential value of such data-sharing initiatives for integrative data analysis.

Clinical Guidance

Clinicians should inquire about acute traumatic stress reactions in children with a known, recent trauma exposure. Acute traumatic stress reactions in the first month appear to be fairly common: in this large international dataset, half of the children reported avoidance of thoughts, conversations, or feelings about the trauma, and nearly as many experienced dissociation (altered sense of reality), or intrusive distressing memories.

A significant proportion of children (about 4 in 10) had some degree of impairment in functioning within this first month. Having multiple acute stress reaction was associated with a greater likelihood of impairment.

Regardless of whether formal diagnostic criteria for ASD are met, when a child has three or four acute stress reactions in the early aftermath of trauma exposure, clinicians should consider providing services or additional follow-up to monitor the course of emotional recovery.

These results point the way to future studies that could help to elucidate the nuances of relationships among child ASD symptoms and impairment in an expanded set of acute trauma populations (e.g., in non-industrialized countries, and with a greater range of types of acute trauma). However, given the time needed to collect prospective data to test new diagnostic criteria (and alternatives) in new research studies, we suggest that the 15 studies included in this large combined dataset represent the best currently available data which can inform the DSM-5 ASD symptom count criteria for children. These results strongly suggest that for trauma-exposed children the proposed 8-symptom rule may be too restrictive, and that serious consideration should be given to implementing alternate criteria for children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R21MH086304 from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Disclosure: Drs. Kassam-Adams, Palmieri, Rork, Delahanty, Kenardy, Landolt, Le Broque, Marsac, Meiser-Stedman, Nixon, and Bui, and Ms. Kohser and McGrath report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Nancy Kassam-Adams, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Patrick A. Palmieri, Summa Health System.

Dr. Kristine Rork, University Hospitals, Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospitals, Case Western Reserve University.

Dr. Douglas L. Delahanty, Kent State University.

Dr. Justin Kenardy, University of Queensland, Australia.

Ms. Kristen L. Kohser, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Markus A. Landolt, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Switzerland.

Dr. Robyne Le Brocque, University of Queensland, Australia.

Dr. Meghan L. Marsac, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Richard Meiser-Stedman, Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Dr. Reginald D. V. Nixon, Flinders University, Australia.

Dr. Eric Bui, Universite de Toulouse and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Toulouse, France, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School.

Ms. Caitlin McGrath, University of Queensland, Australia.

- 1. Kassam-Adams N. The acute stress checklist for children (ASC-Kids): Development of a child self-report measure. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(1):129–139. doi: 10.1002/jts.20090. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Miller A, et al. A diagnostic interview for acute stress disorder for children and adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:549–556. doi: 10.1002/jts.20471. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Bryant R, et al. A review of acute stress disorder in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:802–817. doi: 10.1002/da.20737. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Carrion V, et al. Toward an empirical definition of pediatric PTSD: The phenomenology of PTSD symptoms in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):166–73. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Meiser-Stedman R, et al. The posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis in preschool- and elementary school-age children exposed to motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1326–1337. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081282. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Scheeringa M, Zeanah C, Cohen J. PTSD in children and adolesccents: Toward an empirically based algorithm. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:770–782. doi: 10.1002/da.20736. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Friedman M, et al. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:750–769. doi: 10.1002/da.20767. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Bryant B, et al. Psychological consequences of road traffic accidents for children and their mothers. Psychol Med. 2004;34:335–346. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001053. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Bryant R, Salmon K, Sinclair E. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in injured children. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1075–1079. doi: 10.1002/jts.20282. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Harvey A, Bryant R. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective evaluation of motor vehicle accident survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;67(3):507–512. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.507. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Kassam-Adams N, Winston FK. Predicting child PTSD: The relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD in injured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):403–411. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Harvey A, Bryant R. Two-year prospective evaluation of the relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):626–628. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.626. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Dyregrov A, Kuterovac G, Barath A. Factor analysis of the impact of Event Scale with children in war. Scand J Psychol. 1996;37(4):339–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1996.tb00667.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Perrin S, Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P. The Childrens Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): Validity as a Screening Instrument for PTSD. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2005;33:487–498. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Silverman W, Albano A. Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM–IV: Child and Parent Interview Schedule. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Curran P, Hussong A. Integrative Data Analysis: The simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(2):81–100. doi: 10.1037/a0015914. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. DSM-5 Impairment and Disability Assessment Study Group. [accessed February 14, 2012];Mental Disorders: Separating Symptoms and Disabilities in the DSM-5 [White Paper] 2010 http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/Documents/ProposedDefin-MentalDisorder_IDASG.pdf .

- 18. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guideline. London: 2005. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Berkowitz SJ, Stover CS, Marans SR. The Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention: secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(6):676–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02321.x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Le Brocque RM, Hendrikz J, Kenardy JA. The course of posttraumatic stress in children: Examination of recovery trajectories following traumatic injury. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:637–645. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp050. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Meiser-Stedman R, et al. Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents involved in assaults and motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1381–1383. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1381. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Nixon R, et al. Screening and predicting posttraumatic stress and depression in children following single-incident trauma. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39(4):588–596. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486322. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Research Councils UK. [accessed February 14, 2012];RCUK Common Principles on Data Policy. http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/research/Pages/DataPolicy.aspx .

- 24. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding. Paris, France: OECD Publications; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. National Institutes of Health. [accessed February 14, 2012];Final NIH Statement on Sharing Research Data (NOT-OD-03-032) 2003 Feb 26; http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-03-032.html .

- 26. Feinberg M. Demographic and psychological concomitants of ASD and PTSD: An analysis of children after traffic injury. Graduate School of Education, Univ. of Pennsylvania; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Fein J, et al. Persistence of posttraumatic stress in violently injured youth seen in the emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(8):836–840. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.836. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Kassam-Adams N, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial assessing secondary prevention of traumatic stress integrated into pediatric trauma care. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(3):252–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.20640. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Kenardy J, et al. Information provision intervention for children and their parents following pediatric accidental injury. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(5):316–325. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0673-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Cox C, Kenardy J. A randomised controlled trial of a web-based early intervention for children and their parents following accidental injury. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:581–592. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp095. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Briere J. Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Zehnder D, Meuli M, Landolt M. Effectiveness of a single-session early psychological intervention for children after road traffic accidents: A randomised controlled trial. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2010;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Steil R, Füchsel G. Interviews zu Belastungsstörungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (IBS-KJ) Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (385.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Acute Stress Disorder: A Case Study

I agree the similarity of Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can lead to misdiagnose, but another issue is clinicians who have limited experience with patients who are having issues. Also, as you stated Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) is a condition that only last for about a month and if the condition goes pass a month, the condition will be reevaluate and diagnosed as Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For clinicians to determine the differences in condition and the length of time the condition will last is essential in knowing how to diagnose the condition. The impact of PTSD has grown, especially within the military and being able to identify the difference is vital throughout treatment.

Kelly Asd Case Study

Since Kelly’s symptoms have appeared in the last month therefore her diagnosis is ASD. If it were Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), her symptoms would not have been apparent yet. If Kelly would have not been referred to counseling before now or the traumatic event

Traumatic Events That May Trigger Ptsd

PTSD is considered one of the newest diagnoses, but the notion has been around for years. The APA defines this disorder “as an anxiety (emotional) disorder which stems from a particular incident evoking significant stress (Chu, 2011).According to the National Institute of Mental Health, “traumatic events that may trigger PTSD include violent personal assaults, natural or human-caused disasters, accidents, or military combat (Wilson & Keane, 2004). The history of this disorder is usually centered on wars that have occurred over the years which had left many combat veterans tormented by the events that happened. Although PTSD was first publicly revealed in its connection with military war veterans, it also was recognized in victims that suffered from rape, robbery, torture, captives, wrecks/crashes (plane, car, boat, or any other type of vehicle involved), and natural disasters (floods, hurricanes, and tornadoes). These events are not the normal experiences that are exposed to the human race (serious illness, divorce, and other downfalls of life) which most people were capable with coping with the stressors that came about from such ordinary events (Chu, 2011). Every one that is exposed to some type of traumatic event or events doesn’t develop PTSD which is one of the reasons it was confronted with doubt and dismissal from the general community. Before PTSD was accredited, many people were under the impression that those who were affected (showing the symptoms of PTSD)

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder ( Ptsd )

Then there is the Acute Stress Disorder. This type of PTSD is eminent by panic reactions, mental confusion, suspiciousness, and being unable to manage basic self care and relationship activities. Individuals (victims) of this form of PTSD have gone through more than one traumatic event in order to have these symptoms, events that are a disaster, such as being revealed to a death, or the loss of a home or community.

According to PTSD United, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder used to be considered a psychological condition of combat veterans who were “shocked” by and unable to face their experiences from battle. Soldiers with symptoms of PTSD often faced rejection by their military peers and were feared by society in general. Those who showed signs of PTSD were often removed from combat zones and even discharged from military services, being left labeled as weak (“Post Traumatic Stress”). These implications have been debunked by modern day medical professionals who have given a new definition to the illness to help diagnose those who have it. “PTSD is recognized as a psychological mental disorder that can affect survivors not only of combat experience,

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

so closely related to acute stress disorder, those who may thing they suffer from PTSD need to

“Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” 2014 states symptoms usually begin early, within 3 months of the traumatic incident, but sometimes they begin years afterward. For symptoms to be considered under the category of PTSD, they must last for over a month and must be reoccurring. Every person is different. Sometimes people can be cured of PTSD within six months and it would have been acute or even temporary PTSD, but others could take years to be cured which at that point it would be considered as chronic or long-term PTSD. A doctor who has experience helping people with mental illness, such as a psychiatrist, or a psychologist, can diagnose PTSD. As mentioned before, to be diagnosed with PTSD it must be a reoccurring symptom, but anyone can just claim a reoccurring symptom and call it PTSD. “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” 2016 stated that the specifics are at least one re-experiencing symptom, at least one avoidance symptom, at least two arousal and reactivity symptoms and at least two cognition and mood symptoms.

PTSD has not always had an official diagnosis. Prior to the official diagnosis, there was a large gap in psychiatry. Physicians and other members of society mistreated and regularly disregarded those who

Firstly, Post Tramatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), is a relatively new diagnosis amongst the psychiatric association. This diagnosis is for the individuals who have been involved or witnessed a tramatic event and experience anxiety, re-experienceing event symptoms, whom avoid situations, display a negative change in feelings or beliefs, or experiencing hyperarousal. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was officially awcknowledged as a diagnosis in 1980 by The American Psychiatric Association (APA). The PTSD diagnosis was put into place to describe an individual who had been subjected to an event/s that were dangerous and terrifying leaving the individual feeling frightened and stressed even after there is no imminent danger or reason to feel endangered. An individual is diagnosed with Post Tramatic Stress Disorder if the symptoms keep reoccurring usually if the symptoms last more than six months to a year.

Similarities Between Combat Stress And PTSD

According to the article, Combat stress and PTSD are very different. Yet, sometimes they look quite similar which makes them somewhat complicated. PTSD refers to a psychiatric disorder which impairs functioning. It is considered very serious whereas combat stress is considered standard. Combat stress is an expected and predictable reaction to combat experiences. There are some overlap between combat stress responses and PTSD symptoms, but they are addressed in the same way. combat stress isn’t considered a medical problem or something that needs treatment. However, if service members don’t do certain things, combat stress can persist or morph into something else (like PTSD, depression, an alcohol problem, etc.).

The Life of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Essay examples

- 9 Works Cited

There are people who believe that Post-traumatic Stress disorder is not a real disease, and the victims are feigning their symptoms. These ignorant people have never talked to someone plagued by the disorder. Jonathan Norrell was a medic who was sent to Iraq. Throughout his tour there he witnessed many people die. In an interview with PBS new affiliate Maria Hinojosa, Norrell was asked if “[He] could still do a good job, if [he] could still be a good solider?”(Pertaining to his first brush with death) Norrell’s immediate response was “Yes.” Although he had witnessed a lot of suffering as a medic, the trauma had yet to affect him. However it did. In that same interview Norrell said “It wasn’t till later on that it really started to get to me.” The trauma had taken a life of its own. On the way back to his grandmother’s house in Texas, he had a breakdown where he was crying, couldn’t see, and had no idea where he was . In one conversation with Norrell it would be easy to see how real PTSD really is. Norrell has experience great traumas, and had an intense reaction to them; the recipe for Post-traumatic Stress disorder.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder ( Ptsd ) Essay

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is a disorder that is the result of a traumatic event. According to the national PTSD center in the U.S Department of Veterans Affairs, about 50% of women experience at least one trauma in their lives, traumas like Rape or child abuse are more common in women than in men. About 60% of men experience a trauma in their lives, traumas more related to physical assault, combat, disaster or witnessing a death. Post-Traumatic stress disorder can happen to anyone. In the United States about 8% of the population will have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder at some point in their lives. A disorder similar to Post-Traumatic Stress disorder is Acute Stress Disorder the only difference is that a diagnosis for Acute Stress Disorder has to be given in the month following the traumatic event, for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder to be diagnosed the symptoms have to be recurrent for at least a month after the traumatic event. Good examples are some cases of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder like Maria and Joe a rape victim and a veteran both diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress disorder their symptoms and treatment. Also a case study for suicides involving veterans from the Vietnam war and Somalia peace keeping conflict, 4 veterans diagnosed with PTSD that committed suicide analyzing their major life events and the psychological factors that could have contributed to the suicide.

Ptsd Or Traumatic Stress Disorder Essay

PTSD or (post traumatic stress disorder) is a relatively new diagnosis but the concept of it has somewhat been of a long history. It was often linked to people who have been exposed to combat or have involved in maternal disasters, mass catastrophes, and or serious accidents, Although little has been learned about the disorder in 1952 the first diagnosis appeared in the official nomenclature when diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. But later changed In the midst of the Vietnam war when more cases started popping up, so much in fact provoked a more thorough examination of the disorder. Before the name was created it was defined specifically as a stress disorder that is a common pathway occurring as a consequence from many types of stress. Throughout the years the definition of PTSD has filled an Important void in clinical psychiatry and while the disorder is common the symptoms are fairly easy to spot, people who show signs of PTSD are more likely to experience negative change in beliefs and behavior, they tend to experience moments when they have brief but vivid flashbacks of very traumatic moments also they have inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event. Other symptoms include trying to avoid thinking or talking about the traumatic event,Avoiding places, activities or people that remind you of the traumatic event, PTSD symptoms can intensity over time. You may have more PTSD symptoms when you 're stressed in general, or

Post-traumatic stress disorders also none as PTSD. In 1980 the American psychiatric association added PTSD to the third edition of its diagnostic and statistical manual of mental diagnostic nosologic classification scheme although controversial when first introduced the PTSD diagnosis has filled an important gap in psychiatric theory and practice from an historical perspective the significant change ushered in by the PTSD concept was the stipulation that that the etiological agent was outside the individual traumatic event rather than an inherent individual weakness traumatic neurosis they key to understanding the scientific basis and clinical expression of PTSD is the concept of trauma. The formulation a traumatic event was conceptualized as catastrophic stressor that was outside the range of usual human experiences. The framers of the original PTSD diagnosis had in mind events such as war, torture, rape, natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and volcano eruptions and human made disaster such as airplanes crashes, and automobile accidents they considered traumatic events to be clearly different from the very painful stressors that constitute the normal vicissitudes of life such as divorce, failure, rejection, serious illness, financial reverses, and the like by the logic adverse psychological responses to such ordinary stressors would be characterized as adjustment disorders rather than PTSD this dichotomization between

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (ASD)

Anyone can experience a traumatic event, for example, a car accident or a physical assault during a robbery. In most situations people will develop resilience, which is the person’s ability to adapt when they are faced with trauma, adversity, or high amounts of stress (American Psychological Association, 2016). In other words they are able to cope with the traumatic event, a constructive manner. However there are those who are unable to reach this phase and thus develop a Trauma – and – Stressor Related Disorder. The most common heard of disorder in this category is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), yet there is another disorder that is very similar, Acute Stress Disorder (ASD).

Stress Intervention Services: A Case Study

The research explored the factors which influence officer willingness to use stress intervention services after it had been noted that police officers were often reluctant to use stress intervention services. The study used a quantitative approach and employed a survey method to gather data from 673 police officers focusing on key independent variables of confidentiality and stigma, perceived organisational support and confidence in service providers. Stratified random sampling was employed to ensure that all police departments were represented in the study. Data was analysed using multiple regression.

Related Topics

- Schizophrenia

- Major depressive disorder

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- Free Essays

- Citation Generator

Acute Stress Disorder Case Study

You May Also Find These Documents Helpful

Dsm-5 diagnostic criteria.

Therefore he met two of the five symptoms in Criteria B. Repeatedly upsetting dreams in which the substance effect of the dream are identified with the traumatic event(s). He encounters intense nervousness, sweating, and nausea when in an motor vehicle. Upsetting distressing memories of the awful accident. Mr. smith additionally demonstrated symptoms set apart by physiological responses to interior or outside prompts that symbolize or look like the horrendous…

Montana Diagnostic Report

The patient notices them and goes to get evaluated by a health practitioner. Medical symptoms are important when assessing ones psychological behavior. A head injury may be a primary cause in why the patient acts the way they do. Sadie has suffered with mild to chronic injuries based on her attack. She is walking with a cane and is also limping. She has medical braces on her arm and several scars on her face. She mentioned having a cut on her throat and several broken bones. She’s getting little to no sleep and has repeated nightmares, which causes her cold sweat, heart pounds, and shortness of breath. She’s also prescribed Oxies and is slightly hooked on them. These symptoms are in fact psychological and physical wounds. Symptoms, such as disturbing recurring flashbacks, repeated nightmares, and hyper arousal, continue for more than a month after the occurrence of a traumatic event are a diagnosis of Posttraumatic stress disorder. PTSD may develop after a person is exposed to one or more traumatic events, such as sexual assault, warfare, serious injury, or threats of imminent…

Josh's Anchoring Diagnosis: A Case Study

In order to qualify for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), there is long list of symptoms that are to be experienced by the individual. The primary symptoms of PTSD are intrusive thoughts and memories of the traumatic event (Leahy & Holland, 2000, p. 265). According to Leahy and Holland (2000), these memories can occur through nightmares and flashbacks happening at any time in which the person relives the situation (p. 265). Ultimately, these “attacks” are considered a type…

abnormal psychology study guide

Symptoms: Exposure to a traumatic event, Recurrent involuntary distressing memories, flashbacks, &/or dreams, Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with event, Negative changes in cognitions and moods, Marked changes in arousal and reactivity, Significant distress lasting longer than a month…

Psy 628 Stress Management Research Paper

Maladaptive thoughts, which might have led to increased stress for this student include the extent of problems. Looking at a health perspective, this student could be having anxiety, which will bring on shortness of breath rapid heart rates. This student is increasing stress while talking him or her into a heart attack. Looking at the diet, he or she may put more stress on themselves by not going to the gym and giving into the fast food. Thoughts could be “why change, it will be the same”. Maladaptive thoughts can harm a person. Reading into the negatives will lead to acting in negative ways.…

Cris 304 Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Research Paper

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a widespread disorder that effects a parsons psychologically, behaviorally and emotionally following an experiencing of an traumatic event such as war, rape or abuse. (Schiraldi 2009 p.3) Due the recent wars of Iraq and Afghanistan this disorder has made it’s way to the front of our society. However It is nothing new through out history PTSD has been called by different names such as “ Soldier’s heart” during the Civil war “shell shock “ in World war 1, “combat fatigue" in World war 2, and during the Vietnam war “Vietnam veteran syndrome.”( Adsit 2008 p.23) It is estimated that there over over 400.000 Vietnam war veterans who suffer form PTSD, 38 percent of Operation enduring freedom and Operation Iraq freedom who sought care received a diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder( Adsit p.23)This paper will address factors necessary to copying successfully with the disorder, current professional treatments approaches as well as spiritual applications.…

The Acute Stress Response

The purpose of this paper is to define and explain the acute stress response and acute stress disorder. Clarify the differences between the two conditions and offer review of treatments and symptoms associated with both. Therapies and interventions are reviewed and explored for effectiveness in resolving symptoms and preventing post-traumatic stress disorder. The acute stress response (ASR) refers to psychological and physiological responses to stressful events. These responses are displayed by emotional, cognitive, and behavioral changes. Somatic symptoms and symptoms of mental illness can also be seen in ASR especially when the reaction is severe. ASR manifests itself after the occurrence of a traumatic event and its symptoms can be unstable and complicated. The severity of ASR symptoms can lessen as time passes, but not for everyone. How a person recovers from the initial stress response depends on many factors. The emotional and physical health of the individual, past traumatic experiences, level of perceived threat, and the severity of the event. Age plays a role as well, with children responding and presenting differently from adults due to developmental processes. Adults are better able to verbalize their experiences and feeling where as children are unable to do so putting them at higher risk for a long term stress disorder. It is crucial to provide early intervention to help people cope with the emotional, physical, cognitive, and psychological effects of the acute stress response.…

Trauma And Stressor-Related Disorder Research Paper

Trauma- and stressor-related disorders are psychological illnesses that are triggered by traumatic events experienced by an individual. These debilitating disorders include reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder, acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and adjustment disorders. Traumas that can trigger one of these disorders include sexual victimization, involvement in battle or war, or any other traumatic event especially those which are interpersonal. Assessing those who may suffer with a trauma- or stressor-related disorder can prove to be difficult. A practitioner must be culturally sensitive. One…

Archetype Trauma

When discussing these symptoms, it is useful to turn to one type of trauma, PTSD, as it provides clarity about the effects of trauma. Some indications of PTSD and typical internal trauma include short term memory loss and various psychological repercussions, specifically extreme irritability, irrepressible anger, and hypervigilance. Besides these short term affects, there are also a variety of long term affects associated with trauma. These individuals frequently struggle with trusting others, cognitive processing, and their bodies become hypersensitive to potential threats. After time, these symptoms lessen in severity, however - according to the majority of medical practitioners – they will rarely disappear. Moreover, according to a 2010 study conducted by the National Society of PTSD, ten percent of women and five percent of men in the United States will undergo psychological symptoms of PTSD for…

Trauma-Related Disorder Research Paper

Trauma- and stressor-related disorders look into the psychological distress that comes after an event that is a very stressful or traumatic event. There are many different disorders within this spectrum that include: reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorder. This study focuses on the disorders falling in the category of trauma- and stressor-related and the treatment that is best for each individual disorder.…

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Analysis

Imagine, the face of your attacker haunting your dreams every night or the excruciating reliving of the death of your comrade at the hands of the enemy. You are constantly overcome by a feeling of unexplainable immense dread and grief. This is the pain that people with post-traumatic stress disorder face on a daily basis.…

Stress Disorders

There are several events that can trigger a stress disorder. Combat is a major even that may cause acute stress disorder or PTSD. Natural disasters are also responsible for triggering stress disorders. Victimization and terrorism may also cause stress disorders.…

Acute Stress Disorder

Acute stress disorder develops within one month after an individual experiences or sees an event involving a threat or actual death, serious injury, or physical violation to the individual or others, and responds to this event with strong feelings of fear, helplessness or horror. The disorder is not inherited.…

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a term that many people are familiar with. We hear this on the news or read about it in the newspaper from time to time. Post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD for short is often included in conversations discussing people who have survived some sort of life threatening danger or trauma. Post-traumatic stress disorder causes its victims to feel frightened, worried and stressed in normal situations in which an unaffected person would feel comfortable. Symptoms of PTSD fall into three main categories which are reliving, avoidance and arousal. An example of reliving would be described as having it disturb your day to day activity. Avoidance would be described as being emotionally numb or feeling as though you don’t care about anything and feeling detached or showing less of your moods. Arousal would be described as difficulty concentrating or being startled easily. Being hyper vigilant, feeling irritable or having an outburst of anger. There are many victims of this disorder but the focus in the past few years has seem be on war veterans and has been the cause of much study.…

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Analysis

A person can be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) upon the experience of a traumatic event. PTSD also involves the constant reliving of the trauma and have symptoms of irritability, insomnia, or emotional outburst. In recent studies, patients with PTSD were found to be linked with having high levels of lower back or neck pain. This pain is believed to be a psychological outcome of PTSD rather than physical effect of it. Dunn, Passmore, Burke, and Chiconie (2009) were interested in seeing the effect of chiropractic care on the lower back or neck pain in veterans. 354 veterans were the participants for the study, and roughly 56 (16%) of the participants had a diagnosis of PTSD. During 2006 the participants underwent chiropractic…

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Jun 13, 2020 · Acute Stress Disorder Case Study. Dylan is a male, 15-year-old high school student, who has recently been involved in a severe car accident with two of his classmates. On the day of the accident, he was sat in the front passenger seat, pulling out of a driveway.

This case revolves around a 24 year old young girl who was brought to the psy-chiatry ward on account of hysterical behavior, such as crying, laughing, self-talk and disorientation. Her symptoms fulfilled the DSM-IV-TR criteria of Acute Stress Disorder and Sibling Relational Problem (DSM-IV-TR, 2000).

Oct 16, 2017 · This case report presents a 10-year old girl child that presented with an acute stress disorder after being rescued from a state of burial for three and half hours inside a demolished house ...

Nov 23, 2023 · This case study delves into the experiences of Alex. he is a 32-year-old individual who developed Acute Stress Disorder following a traumatic incident. The aim is to explore the symptoms, causes, and the therapeutic journey toward recovery. Understanding Acute Stress Disorder: Signs, Causes, and Treatment. Background:

3 days ago · Any serious emotional incident--a quarrel with her boyfriend or her boss--sent her over the edge. Her body's response was hyperventilation, palpitations, chest pain, dizziness, anxiety, and a dreadful sense of doom. Stress, in short, was destroying her life. Adapted from The Stress Solution by Lyle H. Miller, Ph.D., and Alma Dell Smith, Ph.D.

Acute Stress Disorder Case Study: Acute stress disorder is the state of the strong anxiety and other symptoms which occur after a shocking accident which has affected the victim’s psychics negatively. the brightest examples of acute stress disorder occur after the tragic experience faced by an individual who has witnessed a car accident, air crash, the fire, the death of a great number of ...

The stated goal of the workgroup developing proposed DSM-5 criteria for acute stress disorder (ASD) is to set criteria that will capture a severity of acute stress reactions within the first month that warrants clinical attention. 3 The workgroup also aims to set diagnostic criteria that will identify a minority of trauma-exposed persons ...

PTSD is considered one of the newest diagnoses, but the notion has been around for years. The APA defines this disorder “as an anxiety (emotional) disorder which stems from a particular incident evoking significant stress (Chu, 2011).According to the National Institute of Mental Health, “traumatic events that may trigger PTSD include violent personal assaults, natural or human-caused ...

Feb 21, 2023 · How common is acute stress disorder? It’s difficult for researchers to assess how common acute stress disorder is. This is partly because people may not seek professional help until their symptoms meet the criteria for PTSD. According to various studies, the prevalence of acute stress disorder following a traumatic event may range from 6% to 33%.

Post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD for short is often included in conversations discussing people who have survived some sort of life threatening danger or trauma. Post-traumatic stress disorder causes its victims to feel frightened, worried and stressed in normal situations in which an unaffected person would feel comfortable.