Impression Management: Erving Goffman Theory

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

- Impression management refers to the goal-directed conscious or unconscious attempt to influence the perceptions of other people about a person, object, or event by regulating and controlling information in social interaction.

- Generally, people undertake impression management to achieve goals that require they have a desired public image. This activity is called self-presentation.

- In sociology and social psychology, self-presentation is the conscious or unconscious process through which people try to control the impressions other people form of them.

- The goal is for one to present themselves the way in which they would like to be thought of by the individual or group they are interacting with. This form of management generally applies to the first impression.

- Erving Goffman popularized the concept of perception management in his book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life , where he argues that impression management not only influences how one is treated by other people but is an essential part of social interaction.

Impression Management in Sociology

Impression management, also known as self-presentation, refers to the ways that people attempt to control how they are perceived by others (Goffman, 1959).

By conveying particular impressions about their abilities, attitudes, motives, status, emotional reactions, and other characteristics, people can influence others to respond to them in desirable ways.

Impression management is a common way for people to influence one another in order to obtain various goals.

While earlier theorists (e.g., Burke, 1950; Hart & Burk, 1972) offered perspectives on the person as a performer, Goffman (1959) was the first to develop a specific theory concerning self-presentation.

In his well-known work, Goffman created the foundation and the defining principles of what is commonly referred to as impression management.

In explicitly laying out a purpose for his work, Goffman (1959) proposes to “consider the ways in which the individual in ordinary work situations presents himself and his activity to others, the ways in which he guides and controls the impression they form of him, and the kind of things he may or may not do while sustaining his performance before them.” (p. xi)

Social Interaction

Goffman viewed impression management not only as a means of influencing how one is treated by other people but also as an essential part of social interaction.

He communicates this view through the conceit of theatre. Actors give different performances in front of different audiences, and the actors and the audience cooperate in negotiating and maintaining the definition of a situation.

To Goffman, the self was not a fixed thing that resides within individuals but a social process. For social interactions to go smoothly, every interactant needs to project a public identity that guides others’ behaviors (Goffman, 1959, 1963; Leary, 2001; Tseelon, 1992).

Goffman defines that when people enter the presence of others, they communicate information by verbal intentional methods and by non-verbal unintentional methods.

According to Goffman, individuals participate in social interactions through performing a “line” or “a pattern of verbal and nonverbal acts by which he expresses his view of the situation and through this his evaluation of the participants, especially himself” (1967, p. 5).

Such lines are created and maintained by both the performer and the audience. By enacting a line effectively, a person gains positive social value or “face.”

The verbal intentional methods allow us to establish who we are and what we wish to communicate directly. We must use these methods for the majority of the actual communication of data.

Goffman is mostly interested in the non-verbal clues given off which are less easily manipulated. When these clues are manipulated the receiver generally still has the upper hand in determining how realistic the clues that are given off are.

People use these clues to determine how to treat a person and if the intentional verbal responses given off are actually honest. It is also known that most people give off clues that help to represent them in a positive light, which tends to be compensated for by the receiver.

Impression Management Techniques

- Suppressing emotions : Maintaining self-control (which we will identify with such practices as speaking briefly and modestly).

- Conforming to Situational Norms : The performer follows agreed-upon rules for behavior in the organization.

- Flattering Others : The performer compliments the perceiver. This tactic works best when flattery is not extreme and when it involves a dimension important to the perceiver.

- Being Consistent : The performer’s beliefs and behaviors are consistent. There is agreement between the performer’s verbal and nonverbal behaviors.

Self-Presentation Examples

Self-presentation can affect the emotional experience . For example, people can become socially anxious when they are motivated to make a desired impression on others but doubt that they can do so successfully (Leary, 2001).

In one paper on self-presentation and emotional experience, Schlenker and Leary (1982) argue that, in contrast to the drive models of anxiety, the cognitive state of the individual mediates both arousal and behavior.

The researchers examine the traditional inverted-U anxiety-performance curve (popularly known as the Yerkes-Dodson law) in this light.

The researchers propose that people are interpersonally secure when they do not have the goal of creating a particular impression on others.

They are not immediately concerned about others’ evaluative reactions in a social setting where they are attempting to create a particular impression and believe that they will be successful in doing so.

Meanwhile, people are anxious when they are uncertain about how to go about creating a certain impression (such as when they do not know what sort of attributes the other person is likely to be impressed with), think that they will not be able to project the types of images that will produce preferred reactions from others.

Such people think that they will not be able to project the desired image strongly enough or believe that some event will happen that will repudiate their self-presentations, causing reputational damage (Schlenker and Leary, 1982).

Psychologists have also studied impression management in the context of mental and physical health .

In one such study, Braginsky et al. (1969) showed that those hospitalized with schizophrenia modify the severity of their “disordered” behavior depending on whether making a more or less “disordered” impression would be most beneficial to them (Leary, 2001).

Additional research on university students shows that people may exaggerate or even fabricate reports of psychological distress when doing so for their social goals.

Hypochondria appears to have self-presentational features where people convey impressions of illness and injury, when doing so helps to drive desired outcomes such as eliciting support or avoiding responsibilities (Leary, 2001).

People can also engage in dangerous behaviors for self-presentation reasons such as suntanning, unsafe sex, and fast driving. People may also refuse needed medical treatment if seeking this medical treatment compromises public image (Leary et al., 1994).

Key Components

There are several determinants of impression management, and people have many reasons to monitor and regulate how others perceive them.

For example, social relationships such as friendship, group membership, romantic relationships, desirable jobs, status, and influence rely partly on other people perceiving the individual as being a particular kind of person or having certain traits.

Because people’s goals depend on them making desired impressions over undesired impressions, people are concerned with the impressions other people form of them.

Although people appear to monitor how they come across ongoingly, the degree to which they are motivated to impression manage and the types of impressions they try to foster varies by situation and individuals (Leary, 2001).

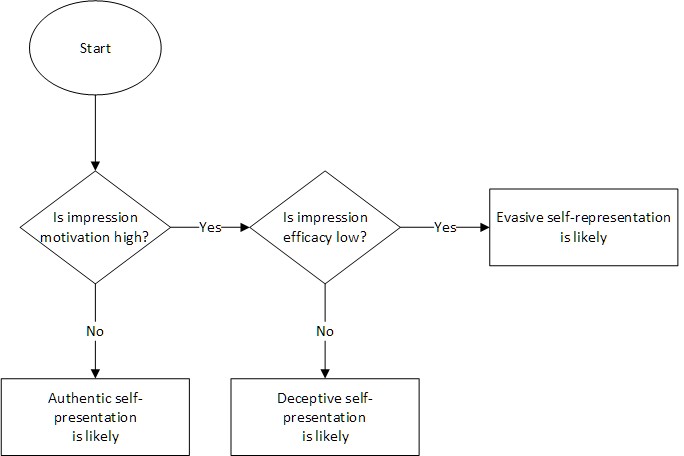

Leary and Kowalski (1990) say that there are two processes that constitute impression management, each of which operate according to different principles and are affected by different situations and dispositional aspects. The first of these processes is impression motivation, and the second is impression construction.

Impression Motivation

There are three main factors that affect how much people are motivated to impression-manage in a situation (Leary and Kowalski, 1990):

(1) How much people believe their public images are relevant to them attaining their desired goals.

When people believe that their public image is relevant to them achieving their goals, they are generally more motivated to control how others perceive them (Leary, 2001).

Conversely, when the impressions of other people have few implications on one’s outcomes, that person’s motivation to impression-manage will be lower.

This is why people are more likely to impression manage in their interactions with powerful, high-status people than those who are less powerful and have lower status (Leary, 2001).

(2) How valuable the goals are: people are also more likely to impress and manage the more valuable the goals for which their public impressions are relevant (Leary, 2001).

(3) how much of a discrepancy there is between how they want to be perceived and how they believe others perceive them..

People are more highly motivated to impression-manage when there is a difference between how they want to be perceived and how they believe others perceive them.

For example, public scandals and embarrassing events that convey undesirable impressions can cause people to make self-presentational efforts to repair what they see as their damaged reputations (Leary, 2001).

Impression Construction

Features of the social situations that people find themselves in, as well as their own personalities, determine the nature of the impressions that they try to convey.

In particular, Leary and Kowalski (1990) name five sets of factors that are especially important in impression construction (Leary, 2001).

Two of these factors include how people’s relationships with themselves (self-concept and desired identity), and three involve how people relate to others (role constraints, target value, and current or potential social image) (Leary and Kowalski, 1990).

Self-concept

The impressions that people try to create are influenced not only by social context but also by one’s own self-concept .

People usually want others to see them as “how they really are” (Leary, 2001), but this is in tension with the fact that people must deliberately manage their impressions in order to be viewed accurately by others (Goffman, 1959).

People’s self-concepts can also constrain the images they try to convey.

People often believe that it is unethical to present impressions of themselves different from how they really are and generally doubt that they would successfully be able to sustain a public image inconsistent with their actual characteristics (Leary, 2001).

This risk of failure in portraying a deceptive image and the accompanying social sanctions deter people from presenting impressions discrepant from how they see themselves (Gergen, 1968; Jones and Pittman, 1982; Schlenker, 1980).

People can differ in how congruent their self-presentations are with their self-perceptions.

People who are high in public self-consciousness have less congruency between their private and public selves than those lower in public self-consciousness (Tunnell, 1984; Leary and Kowalski, 1990).

Desired identity

People’s desired and undesired selves – how they wish to be and not be on an internal level – also influence the images that they try to project.

Schlenker (1985) defines a desirable identity image as what a person “would like to be and thinks he or she really can be, at least at his or her best.”

People have a tendency to manage their impressions so that their images coincide with their desired selves and stay away from images that coincide with their undesired selves (Ogilivie, 1987; Schlenker, 1985; Leary, 2001).

This happens when people publicly claim attributes consistent with their desired identity and openly reject identities that they do not want to be associated with.

For example, someone who abhors bigots may take every step possible to not appear bigoted, and Gergen and Taylor (1969) showed that high-status navel cadets did not conform to low-status navel cadets because they did not want to see themselves as conformists (Leary and Kowalski, 1990).

Target value

people tailor their self-presentations to the values of the individuals whose perceptions they are concerned with.

This may lead to people sometimes fabricating identities that they think others will value.

However, more commonly, people selectively present truthful aspects of themselves that they believe coincide with the values of the person they are targeting the impression to and withhold information that they think others will value negatively (Leary, 2001).

Role constraints

the content of people’s self-presentations is affected by the roles that they take on and the norms of their social context.

In general, people want to convey impressions consistent with their roles and norms .

Many roles even carry self-presentational requirements around the kinds of impressions that the people who hold the roles should and should not convey (Leary, 2001).

Current or potential social image

People’s public image choices are also influenced by how they think they are perceived by others. As in impression motivation, self-presentational behaviors can often be aimed at dispelling undesired impressions that others hold about an individual.

When people believe that others have or are likely to develop an undesirable impression of them, they will typically try to refute that negative impression by showing that they are different from how others believe them to be.

When they are not able to refute this negative impression, they may project desirable impressions in other aspects of their identity (Leary, 2001).

Implications

In the presence of others, few of the behaviors that people make are unaffected by their desire to maintain certain impressions. Even when not explicitly trying to create a particular impression of themselves, people are constrained by concerns about their public image.

Generally, this manifests with people trying not to create undesired impressions in virtually all areas of social life (Leary, 2001).

Tedeschi et al. (1971) argued that phenomena that psychologists previously attributed to peoples’ need to have cognitive consistency actually reflected efforts to maintain an impression of consistency in others’ eyes.

Studies have supported Tedeschi and their colleagues’ suggestion that phenomena previously attributed to cognitive dissonance were actually affected by self-presentational processes (Schlenker, 1980).

Psychologists have applied self-presentation to their study of phenomena as far-ranging as conformity, aggression, prosocial behavior, leadership, negotiation, social influence, gender, stigmatization, and close relationships (Baumeister, 1982; Leary, 1995; Schlenker, 1980; Tedeschi, 1981).

Each of these studies shows that people’s efforts to make impressions on others affect these phenomena, and, ultimately, that concerns self-presentation in private social life.

For example, research shows that people are more likely to be pro-socially helpful when their helpfulness is publicized and behave more prosocially when they desire to repair a damaged social image by being helpful (Leary, 2001).

In a similar vein, many instances of aggressive behavior can be explained as self-presentational efforts to show that someone is willing to hurt others in order to get their way.

This can go as far as gender roles, for which evidence shows that men and women behave differently due to the kind of impressions that are socially expected of men and women.

Baumeister, R. F. (1982). A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 3-26.

Braginsky, B. M., Braginsky, D. D., & Ring, K. (1969). Methods of madness: The mental hospital as a last resort. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Buss, A. H., & Briggs, S. (1984). Drama and the self in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1310-1324. Gergen, K. J. (1968). Personal consistency and the presentation of self. In C. Gordon & K. J. Gergen (Eds.), The self in social interaction (Vol. 1, pp. 299-308). New York: Wiley.

Gergen, K. J., & Taylor, M. G. (1969). Social expectancy and self-presentation in a status hierarchy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5, 79-92.

Goffman, E. (1959). The moral career of the mental patient. Psychiatry, 22(2), 123-142.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Embarrassment and social organization.

Goffman, E. (1978). The presentation of self in everyday life (Vol. 21). London: Harmondsworth.

Goffman, E. (2002). The presentation of self in everyday life. 1959. Garden City, NY, 259.

Martey, R. M., & Consalvo, M. (2011). Performing the looking-glass self: Avatar appearance and group identity in Second Life. Popular Communication, 9 (3), 165-180.

Jones E E (1964) Ingratiation. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York.

Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. Psychological perspectives on the self, 1(1), 231-262.

Leary M R (1995) Self-presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behaior. Westview Press, Boulder, CO.

Leary, M. R.. Impression Management, Psychology of, in Smelser, N. J., & Baltes, P. B. (Eds.). (2001). International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (Vol. 11). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological bulletin, 107(1), 34.

Leary M R, Tchvidjian L R, Kraxberger B E 1994 Self-presentation may be hazardous to your health. Health Psychology 13: 461–70.

Ogilvie, D. M. (1987). The undesired self: A neglected variable in personality research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 379-385.

- Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management (Vol. 222). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Schlenker, B. R. (1985). Identity and self-identification. In B. R. Schlenker (Ed.), The self and social life (pp. 65-99). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schlenker, B. R., & Leary, M. R. (1982). Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization model. Psychological bulletin, 92(3), 641.

Tedeschi, J. T, Smith, R. B., Ill, & Brown, R. C., Jr. (1974). A reinterpretation of research on aggression. Psychological Bulletin, 81, 540- 563.

Tseëlon, E. (1992). Is the presented self sincere? Goffman, impression management and the postmodern self. Theory, culture & society, 9(2), 115-128.

Tunnell, G. (1984). The discrepancy between private and public selves: Public self-consciousness and its correlates. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 549-555.

Further Information

- Solomon, J. F., Solomon, A., Joseph, N. L., & Norton, S. D. (2013). Impression management, myth creation and fabrication in private social and environmental reporting: Insights from Erving Goffman. Accounting, organizations and society, 38(3), 195-213.

- Gardner, W. L., & Martinko, M. J. (1988). Impression management in organizations. Journal of management, 14(2), 321-338.

- Scheff, T. J. (2005). Looking‐Glass self: Goffman as symbolic interactionist. Symbolic interaction, 28(2), 147-166.

Daring Leadership Institute: a groundbreaking partnership that amplifies Brené Brown's empirically based, courage-building curriculum with BetterUp’s human transformation platform.

What is Coaching?

Types of Coaching

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Find your coach

-1.png)

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

The self presentation theory and how to present your best self

Jump to section

What does self presentation mean?

What are self presentation goals, individual differences and self presentation.

How can you make the most of the self presentation theory at work?

We all want others to see us as confident, competent, and likeable — even if we don’t necessarily feel that way all the time. In fact, we make dozens of decisions every day — whether consciously or unconsciously — to get people to see us as we want to be seen. But is this kind of self presentation dishonest? Shouldn’t we just be ourselves?

Success requires interacting with other people. We can’t control the other side of those interactions. But we can think about how the other person might see us and make choices about what we want to convey.

Self presentation is any behavior or action made with the intention to influence or change how other people see you. Anytime we're trying to get people to think of us a certain way, it's an act of self presentation. Generally speaking, we work to present ourselves as favorably as possible. What that means can vary depending on the situation and the other person.

Although at first glance this may seem disingenuous, we all engage in self-presentation. We want to make sure that we show up in a way that not only makes us look good, but makes us feel good about ourselves.

Early research on self presentation focused on narcissism and sociopathy, and how people might use the impression others have of them to manipulate others for their benefit. However, self presentation and manipulation are distinct. After all, managing the way others see us works for their benefit as well as ours.

Imagine, for example, a friend was complaining to you about a tough time they were having at work . You may want to show up as a compassionate person. However, it also benefits your friend — they feel heard and able to express what is bothering them when you appear to be present, attentive, and considerate of their feelings. In this case, you’d be conscious of projecting a caring image, even if your mind was elsewhere, because you value the relationship and your friend’s experience.

To some extent, every aspect of our lives depends on successful self-presentation. We want our families to feel that we are worthy of attention and love. We present ourselves as studious and responsible to our teachers. We want to seem fun and interesting at a party, and confident at networking events. Even landing a job depends on you convincing the interviewer that you are the best person for the role.

There are three main reasons why people engage in self presentation:

Tangible or social benefits:

In order to achieve the results we want, it often requires that we behave a certain way. In other words, certain behaviors are desirable in certain situations. Matching our behavior to the circumstances can help us connect to others, develop a sense of belonging , and attune to the needs and feelings of others.

Example: Michelle is a new manager . At her first leadership meeting, someone makes a joke that she doesn’t quite get. When everyone else laughs, she smiles, even though she’s not sure why.

By laughing along with the joke, Michelle is trying to fit in and appear “in the know.” Perhaps more importantly, she avoids feeling (or at least appearing) left out, humorless, or revealing that she didn’t get it — which may hurt her confidence and how she interacts with the group in the future.

To facilitate social interaction:

As mentioned, certain circumstances and roles call for certain behaviors. Imagine a defense attorney. Do you think of them a certain way? Do you have expectations for what they do — or don’t — do? If you saw them frantically searching for their car keys, would you feel confident with them defending your case?

If the answer is no, then you have a good idea of why self presentation is critical to social functioning. We’re surprised when people don’t present themselves in a way that we feel is consistent with the demands of their role. Having an understanding of what is expected of you — whether at home, work, or in relationships — may help you succeed by inspiring confidence in others.

Example: Christopher has always been called a “know-it-all.” He reads frequently and across a variety of topics, but gets nervous and tends to talk over people. When attending a networking event, he is uncharacteristically quiet. Even though he would love to speak up, he’s afraid of being seen as someone who “dominates” the conversation.

Identity Construction:

It’s not enough for us to declare who we are or what we want to be — we have to take actions consistent with that identity. In many cases, we also have to get others to buy into this image of ourselves as well. Whether it’s a personality trait or a promotion, it can be said that we’re not who we think we are, but who others see.

Example: Jordan is interested in moving to a client-facing role. However, in their last performance review, their manager commented that Jordan seemed “more comfortable working independently.”

Declaring themselves a “people person” won’t make Jordan’s manager see them any differently. In order to gain their manager’s confidence, Jordan will have to show up as someone who can comfortably engage with clients and thrive in their new role.

We may also use self presentation to reinforce a desired identity for ourselves. If we want to accomplish something, make a change, or learn a new skill , making it public is a powerful strategy. There's a reason why people who share their goals are more likely to be successful. The positive pressure can help us stay accountable to our commitments in a way that would be hard to accomplish alone.

Example: Fatima wants to run a 5K. She’s signed up for a couple before, but her perfectionist tendencies lead her to skip race day because she feels she hasn’t trained enough. However, when her friend asks her to run a 5K with her, she shows up without a second thought.

In Fatima’s case, the positive pressure — along with the desire to serve a more important value (friendship) — makes showing up easy.

Because we spend so much time with other people (and our success largely depends on what they think of us), we all curate our appearance in one way or another. However, we don’t all desire to have people see us in the same way or to achieve the same goals. Our experiences and outcomes may vary based on a variety of factors.

One important factor is our level of self-monitoring when we interact with others. Some people are particularly concerned about creating a good impression, while others are uninterested. This can vary not only in individuals, but by circumstances. A person may feel very confident at work , but nervous about making a good impression on a first date.

Another factor is self-consciousness — that is, how aware people are of themselves in a given circumstance. People that score high on scales of public self-consciousness are aware of how they come across socially. This tends to make it easier for them to align their behavior with the perception that they want others to have of them.

Finally, it's not enough to simply want other people to see you differently. In order to successfully change how other people perceive you, need to have three main skills:

1. Perception and empathy

Successful self-presentation depends on being able to correctly perceive how people are feeling , what's important to them, and which traits you need to project in order to achieve your intended outcomes.

2. Motivation

If we don’t have a compelling reason to change the perception that others have of us, we are not likely to try to change our behavior. Your desire for a particular outcome, whether it's social or material, creates a sense of urgency.

3. A matching skill set

You’ve got to be able to walk the talk. Your actions will convince others more than anything you say. In other words, you have to provide evidence that you are the person you say you are. You may run into challenges if you're trying to portray yourself as skilled in an area where you actually lack experience.

How can you make the most of the self presentation theory at work?

At its heart, self presentation requires a high-level of self awareness and empathy. In order to make sure that we're showing up as our best in every circumstance — and with each person — we have to be aware of our own motivation as well as what would make the biggest difference to the person in front of us.

Here are 6 strategies to learn to make the most of the self-presentation theory in your career:

1. Get feedback from people around you

Ask a trusted friend or mentor to share what you can improve. Asking for feedback about specific experiences, like a recent project or presentation, will make their suggestions more relevant and easier to implement.

2. Study people who have been successful in your role

Look at how they interact with other people. How do you perceive them? Have they had to cultivate particular skills or ways of interacting with others that may not have come easily to them?

3. Be yourself

Look for areas where you naturally excel and stand out. If you feel comfortable, confident, and happy, you’ll have an easier time projecting that to others. It’s much harder to present yourself as confident when you’re uncomfortable.

4. Be aware that you may mess up

As you work to master new skills and ways of interacting with others, keep asking for feedback . Talk to your manager, team, or a trusted friend about how you came across. If you sense that you’ve missed the mark, address it candidly. People will understand, and you’ll learn more quickly.

Try saying, “I hope that didn’t come across as _______. I want you to know that…”

5. Work with a coach

Coaches are skilled in interpersonal communication and committed to your success. Roleplay conversations to see how they land, and practice what you’ll say and do in upcoming encounters. Over time, a coach will also begin to know you well enough to notice patterns and suggest areas for improvement.

6. The identity is in the details

Don’t forget about the other aspects of your presentation. Take a moment to visualize yourself being the way that you want to be seen. Are there certain details that would make you feel more like that person? Getting organized, refreshing your wardrobe, rewriting your resume, and even cleaning your home office can all serve as powerful affirmations of your next-level self.

Self presentation is defined as the way we try to control how others see us, but it’s just as much about how we see ourselves. It is a skill to achieve a level of comfort with who we are and feel confident to choose how we self-present. Consciously working to make sure others get to see the very best of you is a wonderful way to develop into the person you want to be.

Unlock personal growth with AI coaching

BetterUp Digital’s AI Coaching delivers personalized strategies to help you improve, grow, and reach your full potential—backed by proven science.

Allaya Cooks-Campbell

With over 15 years of content experience, Allaya Cooks Campbell has written for outlets such as ScaryMommy, HRzone, and HuffPost. She holds a B.A. in Psychology and is a certified yoga instructor as well as a certified Integrative Wellness & Life Coach. Allaya is passionate about whole-person wellness, yoga, and mental health.

Impression management: Developing your self-presentation skills

How self-knowledge builds success: self-awareness in the workplace, 6 presentation skills and how to improve them, how to give a good presentation that captivates any audience, 30 presentation feedback examples, self-awareness in leadership: how it will make you a better boss, developing psychological flexibility, how to make a presentation interactive and exciting, discover how the johari window model sparks self-discovery, how self-compassion strengthens resilience, what is self-efficacy and 10 ways to build it, what is self-awareness and how to develop it, how to not be nervous for a presentation — 13 tips that work (really), what i didn't know before working with a coach: the power of reflection, self-advocacy: improve your life by speaking up, building resilience part 6: what is self-efficacy, why learning from failure is your key to success, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- BetterUp AI Coaching

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case studies

- ROI of BetterUp

- What is coaching?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Personal Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- Content library

- BetterUp Briefing

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Self-Presentation Theory

Self-Presentation Theory: Understanding the Art of Impression Management

In the grand theater of life, where every social interaction is a stage and we are both the actors and the audience, self-presentation theory takes center stage. It whispers the secrets of our performances, the subtle art of crafting personas, and the intricate dance between authenticity and impression. As we pull back the curtain on this psychological narrative, we delve into the depths of human behavior, exploring how the masks we wear and the roles we play are not merely acts of deception but profound expressions of our deepest desires to connect, belong, and be understood in the ever-unfolding drama of existence.

Self-presentation theory, originating from the field of social psychology, delves into the intricate ways individuals strategically convey and portray their desired image to others. This theory explores the underlying motivations and cognitive processes governing how people present themselves in social situations, aiming to understand the dynamics of impression management.

Key Definition:

Self-presentation theory refers to the behavior and strategies individuals use to shape the perceptions that others form about them. This theory suggests that individuals strive to convey a favorable impression to others by managing their public image. It encompasses various aspects such as impression management, identity, and social interaction, and is often associated with social psychology and communication studies. According to this theory, individuals may engage in behaviors such as self-disclosure, performance, and conformity to influence how others perceive them.

Origins and Development

The concept of self-presentation theory was initially formulated by sociologist Erving Goffman, in his seminal work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life , originally published in 1956. Goffman’s was first to create a specific theory concerning self-presentation, laying the foundation for what is now commonly referred to as impression management. His book became widely known after its publication in the United States in 1959.

Goffman’s theory draws from the imagery of theater to portray the importance of human social interaction. He proposed that in social interactions, individuals perform much like actors on a stage, managing the impressions others form of them by controlling information in various ways. This process involves a “front” where the individual presents themselves in a certain manner, and a “back” where they can step out of their role.

His work has been influential in sociology, social psychology, and anthropology, as it was the first to treat face-to-face interaction as a subject of sociological study. Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis observes a connection between the kinds of acts people put on in their daily life and theatrical performances. The theory has had a lasting impact on our understanding of social behavior and continues to be a significant reference point in studies of social interaction.

Impression Management Strategies

Much of Goffman’s early work suggests that “avoidance of shame is an important, indeed a crucial, motive in virtually all social behavior.” Goffman posits that impression management is typically a greater motivation than rational and instrumental goals. Thomas J. Scheff explains that “one tries to control the impression one makes on others, even others who are not significant to one’s life” ( Scheff, 1997. Kindle location: 4,106 ).

Self-presentation theory encompasses a spectrum of strategies employed by individuals to shape others’ perceptions of them. Impression management strategies in social interaction theory are the various techniques individuals use to influence how others perceive them. Individuals employ these strategies to present themselves in a favorable light. The motivation is to achieve specific goals or maintain certain relationships. Here are some key impression management strategies:

- Self-Promotion : Highlighting one’s own positive qualities, achievements, and skills to be seen as competent and capable.

- Ingratiation : Using flattery or praise to make oneself likable to others, often to gain their favor or approval.

- Exemplification : Demonstrating one’s own moral integrity or dedication to elicit respect and admiration from others.

- Intimidation : Projecting a sense of power or threat to influence others to comply with one’s wishes.

- Supplication : Presenting oneself as weak or needy to elicit sympathy or assistance from others.

These strategies can be assertive, involving active attempts to shape one’s image, or defensive, aimed at protecting one’s image. The choice of strategy depends on the individual’s goals, the context of the interaction, and the nature of the relationship.

The Game of Presentation

In many ways, self-presentation opposes other psychology concepts such as authenticity. We adapt to ur environments, and present ourselves accordingly. We act much different at grandma’s house than we do when out drinking with our friends. Perhaps, authenticity is context dependent. However, we can present ourselves differently in different situations without violating core self-values. The presentations may differ but the self remains unchanged.

Carl Jung mused in reflection of his childhood interactions with his friends that, “I found that they alienated me from myself. When I was with them I became different from the way I was at home.” He continues, “it seemed to me that the change in myself was due to the influence of my schoolfellows, who somehow misled me or compelled me to be different from what I thought I was” ( Jung, 2011 ).

Jonathan Haidt suggests that it is merely game. He wrote, “to win at this game you must present your best possible self to others. You must appear virtuous, whether or not you are, and you must gain the benefits of cooperation whether or not you deserve them.” He continues to warn “but everyone else is playing the same game, so you must also play defense—you must be wary of others’ self-presentations, and of their efforts to claim more for themselves than they deserve” ( Haidt, 2003. Kindle location: 1,361 ).

Healthy and Unhealthy Modes of Self-Presentation

We all self-present, creating images that fit the context. While seeking a partner, we self-present a person who is worthy of investing time in. Only in time, do some of these masks begin to fade. Impression management is essential to build new relationships, get the job, and prevent social rejection. Mahzarin R, Banaji and Anthony G. Greenwald wrote, “honesty may be an overrated virtue. If you decided to report all of your flaws to friends and to apply a similar standard of total honesty when talking to others about their shortcomings, you might soon find that you no longer have friends.” they continue, “our daily social lives demand, and generally receive, repeated lubrication with a certain amount of untruthfulness, which keeps the gears of social interaction meshing smoothly” ( Banaji & Greenwald, 2016, pp. 28-29 ).

However, this healthy practice morphs into something sinister when the presented self has nothing to do with the real self. Daniel Goleman refers to individuals that engage in unhealthy deceitful presentations as social chameleons. He wrote, “the social chameleon will seem to be whatever those he is with seem to want. The sign that someone falls into this pattern…is that they make an excellent impression, yet have few stable or satisfying intimate relationships” ( Golman, 2011, Kindle location: 2,519 ).

Goleman explains that “a more healthy pattern, of course, is to balance being true to oneself with social skills, using them with integrity.” He adds, “social chameleons, though, don’t mind in the least saying one thing and doing another, if that will win them social approval” ( Goleman, 2011, Kindle location: 2,523 ).

Situational Influences

The application of self-presentation strategies is contingent upon the social context and the specific goals an individual pursues. In professional settings, individuals may engage in self-promotion to advance their careers, while in personal relationships, they might prioritize authenticity and sincerity. The ubiquity of social media further complicates self-presentation, as individuals navigate the curation of online personas and the management of digital identities.

In the professional realm, the strategic presentation of oneself can play a crucial role in career development and success. This may involve showcasing one’s achievements, skills, and expertise to stand out in a competitive environment. However, it’s important to strike a balance between self-promotion and humility to maintain credibility and foster positive professional relationships.

On the other hand, personal relationships often thrive on genuine connections and authenticity. In these contexts, individuals may choose to present themselves in a sincere manner, emphasizing vulnerability and openness to establish meaningful connections with others. While occasional self-promotion may still occur, the emphasis is more on building trust and rapport.

Social Media and Self-Presentation

The rise of social media has introduced a new layer of complexity to self-presentation. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn offer opportunities for individuals to craft their virtual identities. This process involves selective sharing of information, curation of posts and images, and the management of online interactions. The challenge lies in maintaining a balance between projecting an aspirational image and staying true to one’s authentic self in the digital sphere.

In Goffman’s lengthy comparison between actors and audience suggests that anyone could perform, presenting a certain image. However, he points out that if the actor is a known criminal the audience would not be able to accept their performance, knowing it is a fraud. The actor may enjoy success by going on the road, performing to audiences that are not aware of the actor’s criminal past ( Goffman, 1956, p. 223 ). The internet allows the individual with a shady past to bring their show on the road to an unsuspecting audience who can buy their deceitful performance.

Navigating these diverse self-presentation strategies requires individuals to be mindful of the specific social contexts and their underlying goals. Whether it’s in the professional arena or personal relationships, the nuanced art of self-presentation continues to evolve in the digital age, shaping how individuals perceive and position themselves in the world.

Self-Presentation and Emotional Labor

The intersection of self-presentation theory with emotional labor is a topic of significant interest. Emotional labor pertains to the management of one’s emotions to meet the demands of a particular role or job. Individuals often engage in self-presentation to display appropriate emotions in various settings, leading to a convergence between impression management and emotional regulation. One of the key aspects of this intersection is the impact it has on employee well-being.

Research has shown that the need to regulate emotions in the workplace can lead to emotional exhaustion and burnout. Additionally, there are important implications for organizations, as they have a vested interest in understanding and managing the emotional labor of their employees. Effective programs may enhance employee well-being and improve the quality of service provided to customers. Moreover, the intersection of self-presentation and emotional labor can also be examined through the lens of gender and cultural differences. These examination may highlight the complexities and nuances of this phenomenon in diverse contexts. Understanding this intersection is crucial for creating supportive work environments and fostering healthy, sustainable emotional practices.

See Emotional Labor for more on this topic

Implications and Future Directions

Understanding self-presentation theory has widespread implications, spanning from interpersonal relationships to organizational dynamics. By acknowledging the nuanced strategies individuals employ to shape perceptions, psychologists and practitioners can better grasp human behavior in diverse contexts. Future research may delve into the interplay between self-presentation and cultural factors. In addition, further research may cast light on the psychological effects of sustained impression management on individuals’ well-being.

As individuals, we can understand that we, as well as others, use impression management. Before investing significant resources, we would be wise to try to unmask the presenter and make a decision based on reality rather than expertely presented deceptions.

A List of Practical Implications

Understanding the concepts related to self-presentation theory, such as impression management, self-concept, and social identity, has several practical implications in everyday life:

- Enhanced Social Interactions : By being aware of how we present ourselves, we can navigate social situations more effectively, tailoring our behavior to suit different contexts and relationships.

- Improved Professional Relationships : In the workplace, understanding self-presentation can help in managing professional personas, leading to better workplace dynamics and career advancement.

- Personal Development : Recognizing the strategies we use for impression management can lead to greater self-awareness and personal growth, as we align our external presentation with our internal values.

- Conflict Resolution : Awareness of self-presentation strategies can aid in resolving conflicts by understanding the motivations behind others’ behaviors and addressing the underlying issues.

- Mental Health : Understanding the effort involved in emotional labor and impression management can help in identifying when these efforts are leading to stress or burnout, prompting us to seek support or make changes.

- Authentic Relationships : By balancing self-presentation with authenticity, we can foster deeper and more genuine connections with others.

- Cultural Competence : Recognizing the role of social identity in self-presentation can enhance our sensitivity to cultural differences and improve cross-cultural communication.

Overall, these concepts can empower us to be more intentional in our interactions, leading to more fulfilling and effective communication in our personal and professional lives.

Associated Concepts

Self-presentation theory is intricately connected to a variety of psychological concepts that help explain the behaviors and motivations behind how individuals present themselves to others. Here are some related concepts:

- Self-Concept : This refers to how people perceive themselves and their awareness of who they are. Self-presentation is often a reflection of one’s self-concept, as individuals attempt to project an image that aligns with their self-perception.

- Impression Management : This is the process by which individuals attempt to control the impressions others form of them. It involves a variety of strategies to influence others’ perceptions in a way that is favorable to the individual.

- Social Identity : The part of an individual’s self-concept derived from their membership in social groups. Self-presentation can be used to highlight certain aspects of one’s social identity.

- Cognitive Dissonance : This occurs when there is a discrepancy between one’s beliefs and behaviors. Self-presentation strategies may be employed to reduce cognitive dissonance by aligning one’s outward behavior with internal beliefs.

- Role Theory : Suggests that individuals behave in ways that align with the expectations of the social roles they occupy. Self-presentation can be seen as performing the appropriate role in a given context.

- Self-Esteem : The value one places on oneself. Self-presentation can be a means to enhance or protect one’s self-esteem by controlling how others view them.

- Self-Efficacy : One’s belief in their ability to succeed. Through self-presentation, individuals may seek to project confidence and competence to others, thereby reinforcing their own sense of self-efficacy.

These concepts are interrelated and contribute to the understanding of self-presentation theory as a whole, providing insight into the complex nature of social interactions and the motivations behind individuals’ efforts to influence how they are perceived by others.

A Few Words by Psychology Fanatic

In essence, self-presentation theory captures the multifaceted nature of human interaction, shedding light on the conscious and subconscious processes governing how individuals present themselves in the social arena. By unraveling the intricacies of impression management, researchers continue to unveil the complexities of human behavior and the underlying motivations that propel our interactions with others.

Last Update: April 29, 2024

Type your email…

References:

Goffman, Erving (1956/ 2021 ). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor

Goleman, Daniel ( 2005 ). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books . Read on Kindle Books.

Haidt, Jonathan ( 2003 ). The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. Basic Books ; 1st edition.

Jung, Carl Gustav (1961/ 2011 ). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Vintage ; Reissue edition.

Banaji, Mahzarin R.; Greenwald, Anthony G. ( 2016 ). Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. Bantam ; Reprint edition.

Scheff, Thomas J. ( 1997 ). Shame in Social Theory. Editors Lansky, M. R. and Morrison, A. P. In The Widening Scope of Shame. Routledge ; 1st edition.

Resources and Articles

Please visit Psychology Fanatic’s vast selection of articles , definitions and database of referenced books .

* Many of the quotes from books come books I have read cover to cover. I created an extensive library of notes from these books. I make reference to these books when using them to support or add to an article topic. Most of these books I read on a kindle reader. The Kindle location references seen through Psychology Fanatic is how kindle notes saves my highlights.

Please note that some of the links in this article are affiliate links. If you purchase a product through one of these links, I may receive a small commission at no additional cost to you. This helps support the creation of high-quality content and allows me to continue providing valuable information.

The peer reviewed article references mostly come from Deepdyve . This is the periodical database that I have subscribe to for nearly a decade. Over the last couple of years, I have added a DOI reference to cited articles for the reader’s convenience and reference.

Thank-you for visiting Psychology Fanatic. Psychology Fanatic represents nearly two decades of work, research, and passion.

Topic Specific Databases:

PSYCHOLOGY – EMOTIONS – RELATIONSHIPS – WELLNESS – PSYCHOLOGY TOPICS

Share this:

About the author.

T. Franklin Murphy

Related posts.

Social-Cognitive Theory

Social-Cognitive Theory, formulated by Albert Bandura, emphasizes learning through observation, imitation, and modeling within social contexts. Key concepts include observational learning, self-efficacy, and reciprocal determinism.…

Read More »

Emodiversity

The concept of emodiversity emphasizes the importance of experiencing a wide range of emotions for psychological well-being. Emodiversity involves emotional differentiation, conceptual combination, and has…

Self-Importance

The desire for self-importance is intrinsic to human nature but can lead to unhealthy dynamics in relationships, particularly when one partner's importance threatens the other's.…

Thinking Errors (Cognitive Biases)

We engage in a variety of thinking errors in our pursuit of happiness. If we catch these errors, we can make significant life improvements

Birth Order

The birth order theory, pioneered by Alfred Adler, suggests that a child's position in the family impacts their personality and behavior. Firstborns are often responsible…

Emotional Style

Emotional Style encompasses our individual ways of experiencing and expressing emotions, influencing our emotional traits, states, and moods. Richard Davidson defines six dimensions of Emotional…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from psychology fanatic.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Self-presentation, quick reference.

The conscious or unconscious control of the impression that one creates in social interactions or situations. It is one of the important forms of impression management, namely management of one's own impression on others through role playing. The phenomenon is encapsulated in Shakespeare's famous observation in As You Like It: ‘All the world's a stage, / And all the men and women merely players: / They have their exits and their entrances; / And one man in his time plays many parts’ (II.vii.139–42). It was popularized by the Canadian-born US sociologist Erving Goffman (1922–82) in his influential book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959). See also ingratiation, self-monitoring, social constructionist psychology.

From: self-presentation in A Dictionary of Psychology »

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'self-presentation' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 25 December 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Character limit 500 /500

Self-Presentation Theory (SPT)

Self-presentation theory: a review, introduction.

Self-presentation theory explains how individuals use verbal and non-verbal cues to project a particular image in society (Goffman, 1959). The theory draws on dramaturgy metaphors, such as backstage and frontstage, as a lens to explore human behaviour in everyday life (Goffman, 1959). Using dramaturgy as an analytical tool dates back to Nicholas Evreinov’s (1927) research on theatrical instincts, as well as Kenneth Burke’s (1969) work evaluating and scrutinising dramatic action (Shulman, 2016). Continuing this discourse, Erving Goffman (1959) offered a rich vein of theoretical concepts in sociology by drawing on theatre metaphors. While sociology research at that time focused on broader societal forces and structures, self-presentation theory emphasised individual behaviours and offered a lens to evaluate how performers interact with others to achieve personal goals (Goffman, 1959). Key to self-presentation theory is the notion of impression management and the routines that individuals play to manage an audience’s perception. As a result, self-presentation is crucial in developing one’s social identity. Thus, the theory paved the way for a better understanding of identity development through the performance acts of individuals in society.

Drawing on Goffman’s (1959) theorisation, self-presentation is defined as individuals’ actions to control, shape, and modify the impressions other people have of them in a particular setting. In other words, individuals’ " performance is socialised, moulded, and modified to fit into the understanding and expectations of the society in which it is presented " (Goffman, 1959:p44). Hence, self-presentation holds a strategic value to individuals as impressions influence how others assess, treat, and reward them (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). For instance, in a workplace setting, impressions may shape personal success and career progression (Gardner & Martinko, 1988).

Self-presentation theory draws on the traditions of symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1986). Goffman suggests six key principles of the theory (Goffman, 1959; Shulman, 2016). First, individuals are performers who express their self to society. In practice, individuals highlight a persona and project a particular image to others. Such a projection is a means to show their identity and who they are to the society. Second, individuals want to put forward a credible image. They do so by being truthful and authentic in the way they present themselves. They showcase their expertise in a particular domain. Third, individuals take special care to avoid presenting themselves " out of character ". They strive to ensure that their performance or communication aligns with their role and identity in society. Fourth, if a performance is inadequate and not up to the mark, individuals address or repair it by engaging in restorative actions. Such actions ensure that their desired image is not tarnished. Fifth, self-presentation occurs in social places, known as regions of performance. Such regions in everyday life include the workplace, social gatherings, and social media. As such, they are "platforms" for self-presentation. Sixth, individuals work in teams and manage the impression of the collective to achieve common goals. In other words, a performance may not always occur alone, but can take place in concert with other individuals.

Individuals enact self-presentation because they are motivated to maximise rewards and minimise punishment (Leary & Kowalski, 1990;Schlenker, 1980). More specifically, motivations include the desire to (i) enhance self-esteem, (ii) develop a self-identity, and (iii) generate social and material benefits (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). In practice, people may strive to project an image that will result in praise and compliments, positively shaping one’s self-esteem (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). In contrast, individuals may avoid presenting an image that draws criticism and a lack of self-worth (Cohen, 1959). More specifically, a central motivation for self-presentation is to build an identity in society to foster a unique perception in the minds of others (Schlenker, 1980). Further, self-presentation is an adequate mechanism to foster rewards that can be social, including, trust, affection, and friendship. It can generate material benefits, such as financial gain (Leary & Kowalski, 1990).

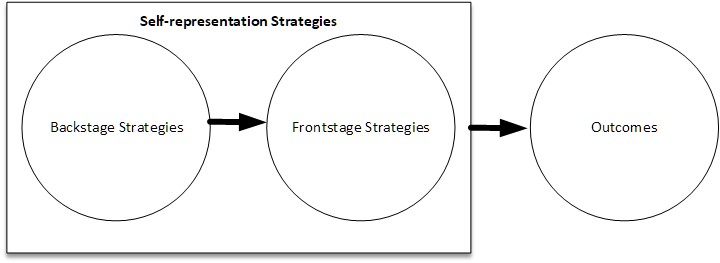

Goffman (1959) uses the dramaturgical metaphor to explain the self-presentation theory and states that " the theatre metaphor is the ‘structure of the social encounter’ that occurs in all social life " (Adams & Sydie, 2002:p170). Drawing on dramaturgical metaphors, self-presentation comprises backstage and frontstage strategies akin to a theatre performance (Cho et al., 2018). These strategies are summarised in Table 1. Backstage relates to reflecting, practising, and taking adequate measures to prepare oneself (Goffman, 1959). Such practices occur in private and offer individuals a more comfortable atmosphere in which to prepare without the pressure from society, such as norms and expectations to behave in a certain way (Jeacle, 2014). The theory suggests the significance of rehearsal, which focuses on preparation work for the frontstage (Siegel, Tussyadiah & Scarles, 2023). For instance, individuals can practise and adjust their presentation at home before a formal client meeting.

Table 1: Self-presentation strategies

In contrast, frontstage comprises the " setting ", which includes the layout and objects in a particular room that set the scene for expression and action (Goffman, 1959). The setting is a place that is usually stable and unmovable, but at times can be relocated such as a circus (Goffman, 1959). Another key aspect of the frontstage is the " personal front ", which relates to personal characteristics such as sex, age, and facial expressions (Goffman, 1959). These characteristics are signals that are either fixed or vary over time (Goffman, 1959). Fixed characteristics are, for instance, one’s ethnic background, whereas characteristics that change include gestures based on one’s mood. The theory suggests that the personal front can be better understood through the lens of appearance and manner. The former relates to one’s temporal state such as work or leisure. The latter expresses the interaction role that one is likely to pursue in a given situation, like being professional and sincere (Goffman, 1959). Usually, there exists a coherence between the appearance and manner, although, at times, they may be misaligned (Goffman, 1959). For instance, a person of high status may behave in a way considered down to earth (Goffman, 1959).

Individuals can enact certain routines as part of their self-expression on the frontstage. At times, these routines can become institutionalised when an individual takes on specific roles in society (Goffman, 1959). The theory highlights the following routines: idealisation, mystification, self-promotion, exemplification, supplication, ingratiation, identification, basking in reflected glory, downward comparison, upward comparison, remaining silent, apology, and corrective action (Schütz, 1998).

Idealisation relates to individuals performing an ideal accredited impression in society (Goffman, 1959). Idealisation is common in social stratification research: individuals strive to go higher up the ladder in the social strata and adjust their self-presentations to reflect that ideal state and value system. In practice, individuals gain insight into the sign equipment required to showcase idealisation, and subsequently use it to project the accredited social class. Mystification is pursued by reducing contact and increasing social distance with the audience to create a sense of awe (Goffman, 1959). It is a means of limiting familiarity with others. For instance, mystification was used by Kings and Queens to foster an impression of power. The audience responded in a way that respected their mystic and sacred identity.

Self-promotion is pursued to create a credible image of oneself in the minds of others (Giacalone & Rosenfeld, 1986; Schau & Gilly, 2003). Such a form of persuasion is relevant in various circumstances, such as job interviews, influencer marketing, and presidential speeches. For instance, a candidate applying for a digital marketing role may share reflections on their expertise in search engine optimisation. An influencer focusing on health and fitness may share online videos of their exercise regimes. A presidential candidate may talk about their vast political experience to project their leadership qualities. Therefore, self-promotion focuses on projecting oneself as an expert and capable person in a particular domain (Bande et al., 2019). However, the theory suggests the issue of misrepresentation: behaviours that represent a false front (Goffman, 1959). Individuals may use credible vehicle signs for the wrong reasons, such as deception and fraud (Goffman, 1959).

Exemplification strategy focuses on creating an impression of oneself as virtuous and honourable (Bonner, Greenbaum & Quade, 2017; Gardner, 2003; Schütz, 1997). In other words, exemplification relates to creating an identity that rests on the notion of morality and ethics. For instance, Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) may publish posts on social media supporting charities, which projects a righteous image. Further, individuals regularly take a stand against harmful organisational behaviours, such as those engaging in child labour. While sharing their views on social media, those individuals exemplify a high moral ground and justify why organisations engaging in transgressions need to be held accountable. However, an exemplification strategy has its potential dangers. The society may question the motive behind such actions and consider it a means to cover up previous unethical deeds (Stone et al., 1997).

Supplication is based on showing oneself as vulnerable and frail to draw adequate support and help from others (Christopher et al., 2005; Korzynski, Haenlein & Rautiainen, 2021) . The ingratiation strategy relates to creating a likable and attractive impression in a particular place offline, such as one’s workplace, and online on social media (Bolino, Long & Turnley, 2016; Gross et al., 2021). For instance, an individual can project themselves to be professional and collegial in the workplace to foster goodwill and social approval.

The identification strategy puts emphasis on associating oneself with a particular community to create a specific image in society (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). For instance, some consumers may link themselves to the Harley-Davidson community to create a rebellious and adventurous image (Schembri, 2009). Tattoos, leather jackets, and riding on Harley motorcycles in packs reinforce their identification (Schembri, 2009). A strategy that slightly overlaps with identification work is " basking in reflected glor y" (Cialdini et al., 1976). In this case, an individual associates themselves with another person who has a positive impression in society and thus leverages those associations (Schütz, 1998).

Downward comparison focuses on projecting oneself as superior and in a positive light to the detriment of others (Wills, 1981). One may witness downward comparison in politics as one presidential candidate expresses how their vision and proposed policies are superior compared to another candidate. Upward comparison, however, is the practice of comparing oneself with someone better to improve one’s self-evaluations and perceptions (Collins, 1996).

Remaining silent may be a particular practice for individuals to be neutral and not face any criticism or backlash (Premeaux & Bedeian, 2003). Finally, particularly when one is responsible for an adverse event or has engaged in a wrong action, they may share an apology, defined as " repenting and promising moral behaviour in the future " (Hart, Tortoriello & Richardson, 2020:p2). They may suggest putting corrective measures in place so that it does not happen again in the future (Schütz, 1998).

Figure 1 offers a generic framework of self-presentation theory, comprising frontstage and backstage strategies that help attain specific outcomes (Goffman, 1959; Leary & Kowalski, 1990). The backstage and frontstage are inter-related. Backstage strategies often involve preparation, desk research, and due diligence to gain insight into a particular performance (Jacobs, 1992). As such, backstage is an unofficial channel for individuals to gain the necessary skills, attributes, and contextual understanding to perform certain routines (Tiilikainen et al., 2024). Subsequently, individuals enact frontstage strategies involving those practised routines and impressions in a social context (Schütz, 1997).

To ensure adequate self-presentation, the theory suggests various means by which impression management can be pursued in the right way and includes defensive and protective practices (Goffman, 1959) as well as maintaining the definition of the situation (Tiilikainen et al., 2024). Defensive practices pursued by performers are a means for individuals and teams to safeguard their own performance. It requires discipline, whereby individuals have " presence of mind ". Disciplined individuals are resilient to unexpected circumstances and are sufficiently agile to ensure the performance attains its goal. In addition, individuals can enact circumspection by adequately preparing to offer a high-quality performance (Goffman, 1959). This involves taking time to design the performance and enacting foresight and prudence. Individuals may even show loyalty and devotion to other team members to ensure the overall impression does not fail (Goffman, 1959). When individuals reveal secrets or problems to outsiders, it damages the image of the team.

Protective practices, however, are pursued by audience members to help the performers manage their impressions (Goffman, 1959). They do so by not intruding on the back or frontstage. In practice, etiquette is maintained by not involving oneself in others' personal matters. Permission and consent are exercised to gain access. For instance, salespersons usually introduce themselves first and ask permission to discuss a product or service. However, the audience can exercise extra understanding and empathy when performance is not up to the mark for a person learning their trade (Goffman, 1959).

Finally, by maintaining a definition of the situation, individuals can develop an " agreed upon, subjective understanding of what will happen in a given situation or setting, and who will play which roles in the action " (Crossman, 2019). As a result, the concept defines the social order and gives symbolic meaning to human interactions that occur in everyday life (Tiilikainen et al., 2024). When the definition of the situation is not maintained or broken, the performance becomes ineffective and may even collapse (Tiilikainen et al., 2024).

Institutions shape how performers present themselves in everyday life. Goffman (1983:p1) used the terminology - interaction order – to explain the " loose coupling between interaction practices and social structure " and how " the workings of the interaction order can easily be viewed as the consequence of systems of enabling conventions, in the sense of ground rules for a game, the provisions of a traffic code or the rules of syntax of a language ". As such, the interaction order offers rules and norms that shape one’s behaviour in society. At an extreme level, institutions can have high levels of dominance and control, which Goffman (1961) defines as total institutions, which are often applied in prisons, military organisations, and even hospitals. Total institutions exert control over individuals’ daily routines, movements, and even identities (Goffman, 1961). The theoretical properties of total institutions include role dispossession i.e., " the process through which new recruits are prevented from being who they were in the world they inhabited prior to entry" (Shulman, 2016:p103). This involves trimming or programming, which relates to individuals being " shaped and coded into an object that can be fed into the administrative machinery of the establishment, to be worked on smoothly by routine operations " (Goffman, 1986:p16). Individuals in a total institution are forced to give up their identity kit i.e., personal belongings that give meaning to who they are in society (Shulman, 2016).

Theoretical developments

Since Goffman’s original work, scholars have advanced the theoretical properties of self-presentation. Specifically, in sharp contrast to total institutions, Scott (2011:p3) suggested the notion of reinventive institutions, defined as "a material, discursive or symbolic structure in which voluntary members actively seek to cultivate a new social identity, role or status. This is interpreted positively as a process of reinvention, self-improvement or transformation. It is achieved not only through formal instruction in an institutional rhetoric, but also through the mechanisms of performative regulation in the interaction context of an inmate culture" . Reinventive institutions are much more relevant in modern life, whereby individuals want to go through a transformation of their self and create a new identity (Scott, 2011). In other words, they want to let go of their previous self in pursuit of a reinvigorated new persona. Illustrative cases of reinventive institutions include spiritual communities and lifestyle groups (Shulman, 2016). Individuals are not forced to enter these communities; rather, they do so entirely voluntarily (Scott, 2010). These institutions are self-organising, i.e., the community members keep a check on each other to maintain the collective norms (Huber et al., 2020).

In contrast to Goffman’s original theorisation of self-presentation in face-to-face, offline interactions, research work has extended the theory to evaluate online impression management (Bareket-Bojmel, Moran & Shahar, 2016; Ranzini & Hoek, 2017; Rui & Stefanone, 2013). In practice, individuals use technology features such as text, images or videos to signal and manage their online image. This contrasts with non-verbal signals, such as body language, which are often common in offline interactions. Online impression management can be managed more conveniently as individuals can develop, change, or edit informational cues in a way that suits their purpose (Sun, Fang & Zhang, 2021). However, individuals’ digital footprint may remain over time online, and it can be viewed and accessed by others anytime (Hogan, 2010). This relates to the problem of " stage breach ", where data about individuals’ private lives are retrievable on search engines and social media platforms (Shulman, 2016). As such, the internet has caused the blurring of boundaries between back and frontstage, a phenomenon dubbed as " collapsed contexts " (Davis & Jurgenson, 2014), defined as " a flattening of the spatial, temporal, and social boundaries that otherwise separate audiences on social networking sites " (Duguay, 2016:p892). In response, individuals may use privacy filters or even delete content posted in the past that may negatively influence their image in society (DeAndrea, Tong & Lim, 2018).

Due to the advent of social media, Hogan (2010) extended Goffman’s theorisation by differentiating between "performances" and "exhibitions" that occur online. Performances, similar to Goffman’s dramaturgy metaphor, occur in real-time, such as in chat rooms, online meetings, and live streams. In this case, the situation is synchronous, and performances are time-bound (Hogan, 2010). However, exhibitions do not occur in real time, and individuals use technology artifacts afforded by social media to curate content (Hogan, 2010). These include posting a status update, uploading a photo album, or sharing a pre-recorded, edited video. As a result, exhibitions occur in asynchronous situations.

Overall, self-presentation theory provides a dramaturgy analytical lens for researchers to evaluate human behaviour in face-to-face and online interactions that involve synchronous and/or asynchronous situations. It offers a range of back and frontstage strategies that individuals and teams enact to manage their impressions in society, also suggesting that the broader institutional environment shapes how they behave in everyday life. Table 2 summarises the key conceptual definitions of self-presentation theory.

Table 2: Key concepts and definitions

Applications