Clive Wearing (Amnesia Patient)

Imagine waking up every day without remembering anything from your past and then immediately forgetting that you woke up at all. This life without memories is the reality for British musician Clive Wearing who suffers from one of the most severe case of amnesia ever known.

Who is Clive Wearing?

Clive Wearing was born on 11 May 1938. He was an accomplished musicologist, keyboardist, conductor, music producer, and professional tenor at the Westminster Cathedral. When on 27 March 1985 he contracted a virus that attacked his central nervous system resulting in a brain infection, Clive’s life was changed forever.

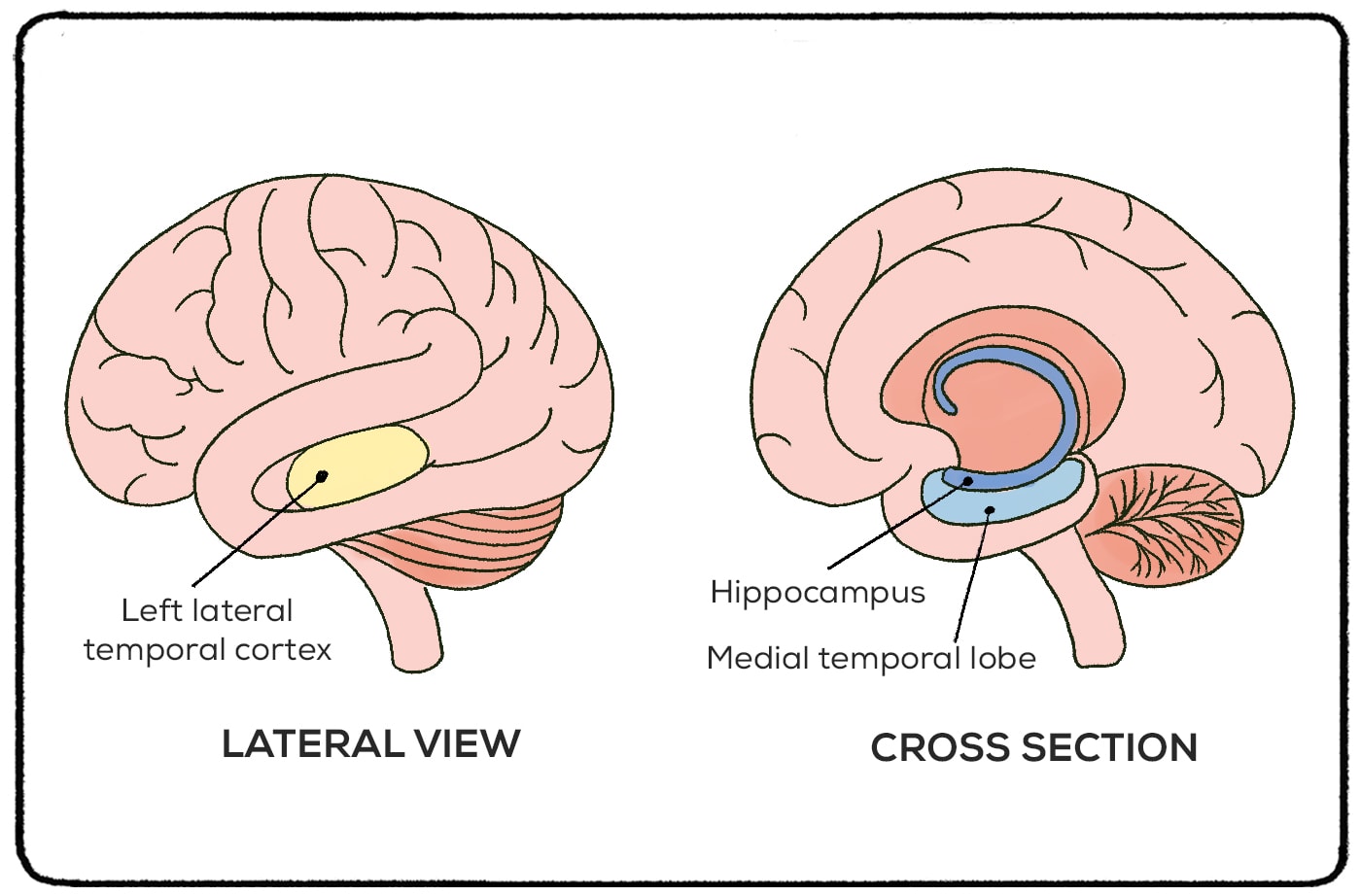

The rare neurological condition called herpes encephalitis caused profound and irreparable damage to Clive’s hippocampus. The hippocampus is a part of the brain that plays an important role in consolidating short-term memory into long-term memory. It is essential for recalling facts and remembering how, where, and when an event happened.

Clive’s hippocampus and medial temporal lobes where it is located were ravaged by the disease. As a consequence, he was left with both anterograde amnesia, the inability to make or keep memories, and retrograde amnesia, the loss of past memories. Most patients suffer one or the other, so it's notable that Clive suffered both.

Clive Wearing and Dual Retrograde-Anterograde Amnesia

Clive’s rare dual retrograde-anterograde amnesia, also known as global or total amnesia, is one of the most extreme cases of memory loss ever recorded. In psychology, the phenomenon is often referred to as "30-second Clive" in reference to Clive Wearing’s case.

Anterograde amnesia

Anterograde amnesia is the loss of the possibility to make new memories after the event that caused the condition, such as an injury or illness. People with anterograde amnesia don’t recall their recent past and are not able to retain any new information. (If you have ever seen the movie 50 First Dates, you might be familiar with this type of condition.)

The duration of Clive’s short-term memory is anywhere between 7 seconds and 30 seconds. He can’t remember what he was doing only a few minutes earlier nor recognize people he had just seen. By the time he gets to the end of a sentence, Clive may have already forgotten what he was talking about. It is impossible for him to watch a movie or read a book since he can’t remember any sentences before the last one.

Because he has no memory of any previous events, Clive constantly thinks that he has just awoken from a coma. In a way, his consciousness is rebooted every 30 seconds. It restarts as soon as the time span of his short-term memory has elapsed.

Retrograde amnesia

Retrograde amnesia is a loss of memory of events that occurred before its onset. Retrograde amnesia is usually gradual and recent memories are more likely to be lost than the older ones .

Due to his severe case of retrograde amnesia, however, Clive doesn’t remember anything that has happened in his entire life. He completely lacks the episodic or autobiographical memory, the memory of his personal experience.

But although he can’t remember them, Clive does know that certain events have occurred in his life. He is aware, for example, that he has children from a previous marriage, even though he doesn’t remember their names or any other detail about them. He knows that he used to be a musician, yet he has no recollection of any part of his career.

Clive also knows that he has a wife. In fact, his second wife Deborah is the only person he recognizes. Whenever Deborah enters the room, Clive greets her with great joy and affection. He has no episodic memories of Deborah, and no memory of their life together. For him, each meeting with her is the first one. But he knows that she is his wife and that he is happy to see her. His memory of emotions associated with Deborah provokes his reactions even in the absence of the episodic memory.

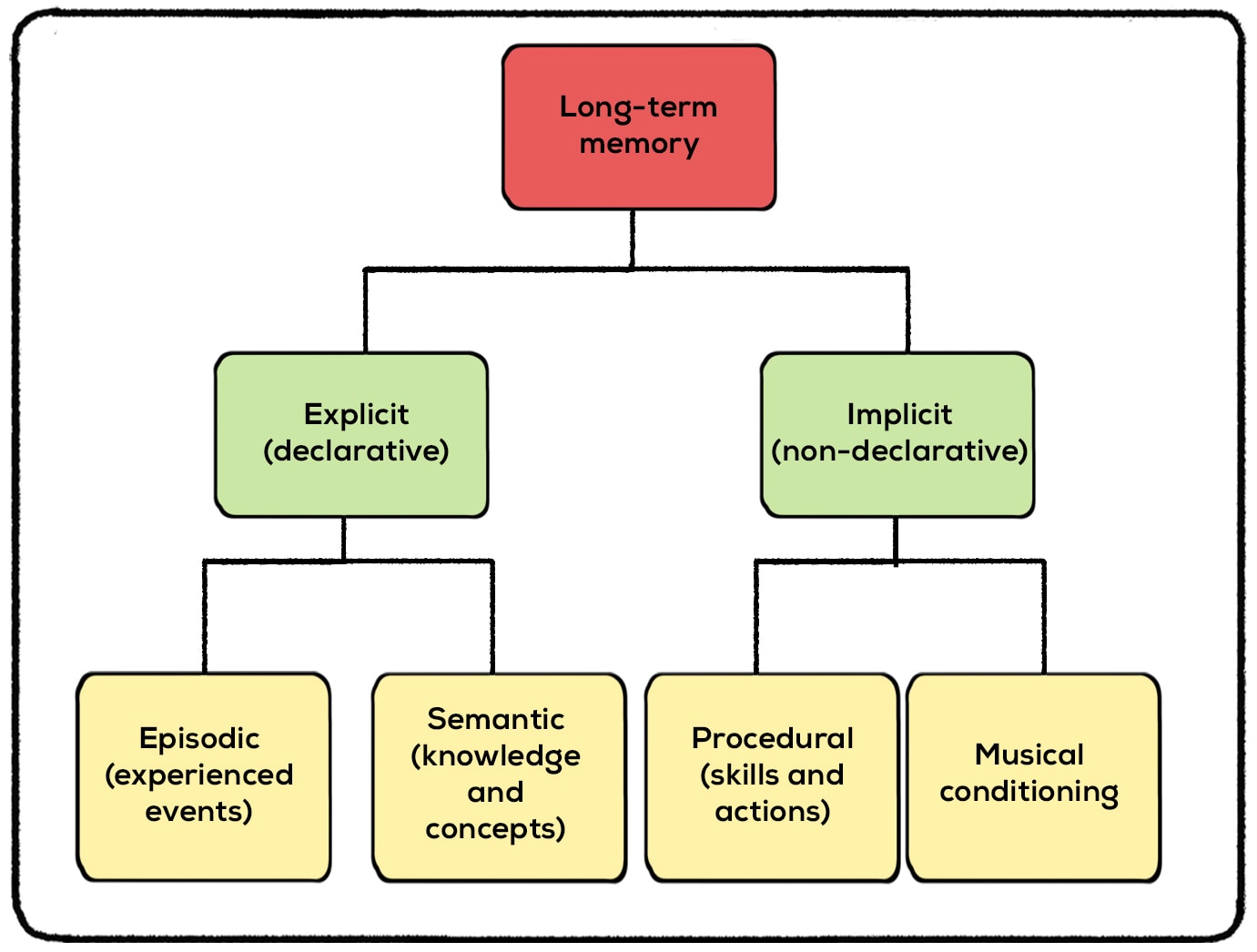

In spite of his complex amnesia, Clive still has some types of memories that remain intact, including semantic and procedural memory.

Clive Wearing’s Semantic and Procedural Memories

Clive Wearing’s example shows that memory is not as simple as we might think. Although the physical location of memory remains largely unknown, scientists believe that different types of memories are stored in neural networks in various parts of the brain.

Semantic memory

Semantic memory is our general factual knowledge, like knowing the capital of France, or the months of the year. Studies show that retrieving episodic and semantic memories activate different areas of the brain. Despite his amnesia, therefore, Clive still has much of his semantic memory and retains his humor and intelligence.

Procedural memory

Clive may not have any episodic memories of his life before the illness, but he has a largely unimpaired procedural memory and some residual learning capacity.

Procedural or muscle memory is remembering how to perform everyday actions like tying shoelaces, writing, or using a knife and fork. People can retain procedural memories even after they have forgotten being taught how to do them. This is why Clive’s procedure memory including language abilities and performing motor tasks that he learned prior to his brain damage are unchanged.

Using procedural memory, Clive can learn new skills and facts through repetition. If he hears a piece of information repeated over and over again, he can eventually retain it although he doesn’t know when or where he had heard it.

While episodic memory is mainly encoded in the hippocampus, the encoding of the procedural memory takes place in different brain areas and in particular the cerebellum, which in Clive’s case has not been damaged.

Musical memory

What’s more, Clive’s musical memory has been perfectly preserved even decades after the onset of his amnesia. In fact, people who suffer from amnesia often have exceptional musical memories. Research shows that these memories are stored in a part of the brain separate from the regions involved in long-term memory.

That’s why Clive is capable of reading music, playing complex piano and organ pieces, and even conducting a choir. But just minutes after the performance, he has no more recollection of ever having played an instrument or having any musical knowledge at all.

Is Clive Wearing Still Alive?

Yes! Clive Wearing is in his early 80s and lives in a residential care facility. Recent reports show that he continues to approve. He renewed his vows with his wife in 2002, and his wife wrote a memoir about her experiences with him.

You can take a look at Clive Wearing's diary entry, as well as access a documentary on him, by checking out this Reddit post .

Not Just Clive Wearing: Other Cases of Amnesia

Clive Wearing is one of the most famous patients with amnesia, but he is far from the only one. Amnesia can affect people temporarily or permanently, and it doesn’t discriminate. Famous authors, former NFL players, and just regular people going to the dentist may deal with a bout of amnesia at one point in their lives. And some of these stories are so stranger than fiction that they are doubted by medical professionals and the general public!

Neuroscientists have been carefully studying amnesia since the 1950s. One of their first notable patients was a man named Henry Molaison, or “H.M.” H.M. suffered amnesia after having surgery at the age of 27. H.M. forgot things almost as soon as they took place. His condition was the subject of studies for decades until he died in 2008. Many scientists still refer to his case when discussing amnesia and other memory disorders.

Scott Bolzan

Imagine waking up one day in the hospital with little to no memories of your life. You’re 47, the woman by your bedside is telling you that you have been married for 25 years. The terms “marriage” and “wife” don’t even register in your brain! As your family tells you about your life, you learn that you spent two years playing in the NFL, have two teenage children, and have decades of memories that just aren’t accessible. This is what happened to Scott Bolzan.

Scott Bolzan developed retrograde amnesia after a simple slip and fall. Little to no blood flow and damaged brain cells in the right temporal lobe erased many of Bolzan’s long-term memories. He knew basic skills, like eating with utensils, but memories of people and events completely disappeared. His case is one of the most severe cases of retrograde amnesia in history, but even his story is doubted by some neurologists. Since his fall, he has written a book about his memory loss and is now a motivational speaker.

Agatha Christie

The story of Agatha Christie’s amnesia is largely buried under her other accomplishments. She’s one of the world’s best-selling authors (only outsold by the Bible and Shakespeare!) Her brain was always in use as she wrote 66 detective novels, but before that, she may have suffered great memory loss. Did she have total amnesia? The jury is actually out on that. I’ll explain why.

Christie found out that her husband was cheating on her shortly after the death of Christie’s mother. The stress was tough for Christie to handle, so it’s not surprising that she fled home after an argument with her husband. Her car turned up in a ditch, and after 11 days of searching, she was found at a hotel. Christie had checked into the hotel using the same name as the “other woman” in her husband’s affair.

Upon discovering Christie, her husband reported that she was suffering from amnesia and had no idea who she was. Two doctors confirmed the diagnosis, but it did not debilitate her for life, like Clive Wearing. This alleged bout with amnesia happened in 1926, years before she wrote the genius novels that we still know today. Some sources are not sure whether she suffered amnesia, was faking the condition to seek revenge on her husband or was simply experiencing a dissociative state after traumatic events. It would not be completely unusual if she did experience memory loss while staying in that hotel. Dissociative amnesia can affect anyone who has been through trauma or extreme levels of stress.

One patient, identified only as “ WO ,” started living the life of Drew Barrymore’s character in 50 First Dates after a…root canal? While anterograde amnesia was the result of a car crash in the popular movie, other types of trauma or events can bring on this condition. For WO, it was a routine root canal. Nothing dramatic happened during the procedure. Nothing dramatic took place in WO’s brain after they went home. And yet, the patient wakes up every day believing it is March 14, 2005. They were 38 years old at the time of the root canal.

Every day, the patient must wake up and remind themselves that it is not 2005, but much later. An electronic journal keeps them up to date with their life and the events of the past years. Although the cause behind their amnesia is truly baffling, it goes to show that our brains can be fragile and there is still a lot to learn about them!

Related posts:

- Long Term Memory

- Semantic Memory (Definition + Examples + Pics)

- Memory (Types + Models + Overview)

- Short Term Memory

- Declarative Memory (Definition + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Clive Wearing’s Case: A Landmark in Memory and Neuropsychology

A mind frozen in time, yet a spirit that endures – this is the captivating paradox of Clive Wearing, whose extraordinary case has revolutionized our understanding of memory and the brain’s profound mysteries. Imagine waking up every few minutes, believing you’ve just regained consciousness for the first time. This is the reality for Clive Wearing, a man whose story has captivated neuroscientists, psychologists, and the general public alike for decades.

Clive’s journey began in 1985 when a seemingly ordinary viral infection turned his world upside down. A successful musician and conductor, Clive was struck down by herpes simplex encephalitis, a rare but severe inflammation of the brain. Little did he know that this infection would rob him of his ability to form new memories and erase much of his past, leaving him in a perpetual state of awakening.

The significance of Clive Wearing’s case in the field of psychology and neuroscience cannot be overstated. It’s like stumbling upon a living, breathing experiment that nature herself designed. His condition has provided researchers with an unprecedented opportunity to study the intricate workings of human memory, consciousness, and the resilience of the human spirit.

The Onset and Nature of Clive Wearing’s Condition

The viral encephalitis that caused Clive’s amnesia was like a wildfire in his brain, specifically targeting areas crucial for memory formation and retrieval. The result? A devastating combination of anterograde and retrograde amnesia. Now, if you’re scratching your head wondering what on earth that means, let me break it down for you.

Anterograde amnesia is like having a faulty ‘save’ button in your brain. Clive can’t form new memories, so each moment feels like the first. On the other hand, retrograde amnesia is like someone hit the ‘delete’ button on his past. Most of his pre-illness memories have vanished into thin air.

The extent of Wearing’s memory loss is staggering. His memory span is typically between 7 to 30 seconds. Imagine trying to have a conversation where you forget what was said half a minute ago. It’s like trying to build a sandcastle while the tide is coming in – frustrating and seemingly futile.

But here’s where things get really interesting. Despite this profound memory impairment, Clive’s musical abilities remained largely intact. He could still read music, play the piano, and conduct a choir. It’s as if the music was etched into his very being, untouched by the ravages of his condition. This preservation of musical ability has provided fascinating insights into the complex nature of memory and skill retention.

Psychological and Neurological Implications

Clive Wearing’s case has been a goldmine for researchers studying the role of the hippocampus in memory formation. This seahorse-shaped structure in our brains is crucial for converting short-term memories into long-term ones. In Clive’s case, the viral infection severely damaged his hippocampi (yes, we have two of them), effectively cutting off this vital process.

This brings us to an important distinction in memory research: short-term versus long-term memory. Clive’s condition beautifully illustrates this divide. His short-term memory, while severely limited, allows him to engage in brief conversations or tasks. However, the bridge to long-term memory is broken, preventing these fleeting moments from becoming lasting memories.

Fascinatingly, Clive’s procedural memory – the type of memory responsible for skills and habits – remained largely intact. This is why he could still play the piano or tie his shoelaces. It’s like his body remembered even when his mind couldn’t. This preservation of procedural memory in the face of severe declarative memory loss has been a cornerstone in understanding the different memory systems in our brains.

Living in the moment takes on a whole new meaning when we look at Clive’s case. From a neuropsychological perspective, his condition forces him to experience each moment as if it were his first. It’s a stark reminder of the role memory plays in our perception of time and self. Without the ability to link past experiences to the present, Clive’s consciousness is reset every few seconds, creating a unique and challenging existence.

Clive Wearing’s Daily Life and Coping Mechanisms

At the heart of Clive’s story is his relationship with his wife, Deborah. Their love story is a testament to the power of human connection in the face of unimaginable challenges. Deborah has been Clive’s anchor in a sea of confusion, providing stability and comfort in his ever-changing world.

The repetitive nature of Clive’s thoughts and actions is a defining feature of his condition. He often writes the same entries in his journal, expressing his belief that he has just woken up for the first time. It’s like watching a record skip, playing the same few seconds over and over again.

Managing Clive’s condition requires a delicate balance of patience, routine, and creativity. Strategies include using visual cues and familiar environments to provide a sense of stability. Music, unsurprisingly, plays a crucial role in his daily life, offering moments of joy and connection to his pre-illness self.

The emotional impact on Clive and his family cannot be overstated. Imagine the frustration of constantly feeling disoriented, or the heartbreak of seeing a loved one struggle to remember you. Yet, through it all, moments of recognition and joy shine through, particularly when Clive is engaged in music.

Contributions to Psychology and Neuroscience

Clive Wearing’s case has been a catalyst for advancements in understanding memory systems. It has challenged previous notions about the nature of memory and consciousness, forcing researchers to reevaluate their theories and approaches.

One of the most significant insights gained from studying Clive is the complex nature of consciousness and self-awareness. Despite his profound memory loss, Clive maintains a sense of self, albeit a fragmented one. This has led to fascinating discussions about the role of memory in identity and consciousness.

The implications for treating memory disorders are far-reaching. By understanding the specific deficits in cases like Clive’s, researchers can develop more targeted interventions for various memory-related conditions. It’s like having a roadmap of what can go wrong in the brain, guiding us towards potential solutions.

Clive’s case has also influenced theories of amnesia and brain plasticity. The preservation of his musical abilities, despite severe memory impairment, has shed light on the brain’s remarkable ability to compartmentalize different types of information and skills. It’s a testament to the brain’s complexity and resilience.

Comparative Analysis with Other Notable Amnesia Cases

While Clive Wearing’s case is extraordinary, it’s not the only one that has shaped our understanding of memory. Let’s take a moment to compare his case with other landmark studies in the field.

H.M. (Henry Molaison) is perhaps the most famous case in memory research. After undergoing surgery to treat severe epilepsy, H.M. lost the ability to form new memories. His case was instrumental in establishing the role of the hippocampus in memory formation. Unlike Clive, H.M.’s retrograde amnesia was less severe, and he retained some memories from his past.

Patient K.C. is another fascinating case that has contributed significantly to our understanding of semantic memory – our general knowledge about the world. K.C. could remember facts but not personal experiences, a stark contrast to Clive who struggles with both.

What makes Wearing’s case unique is the severity of both his anterograde and retrograde amnesia, combined with his preserved musical abilities. It’s like nature designed the perfect experiment to tease apart different aspects of memory and cognition.

These landmark cases, each with their unique characteristics, have collectively painted a rich picture of how memory works in the human brain. They remind us of the complexity of our cognitive processes and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of profound challenges.

The Enduring Legacy of Clive Wearing’s Case

As we reflect on Clive Wearing’s extraordinary journey, we’re reminded of the profound impact one individual can have on our understanding of the human mind. His case has been a wellspring of insights, challenging our preconceptions about memory, consciousness, and the very nature of what it means to be human.

Ongoing research inspired by Clive’s condition continues to push the boundaries of neuroscience and psychology. Scientists are exploring new avenues in memory research, delving deeper into the intricate workings of our brains. It’s like Clive handed researchers a key to unlock some of the most perplexing mysteries of the mind.

But beyond the scientific implications, Clive’s story is a powerful testament to human resilience. Despite living in a world where each moment feels like the first, Clive’s spirit endures. His ability to find joy in music, to connect with his loved ones, even if only for fleeting moments, is a poignant reminder of the strength of the human spirit.

The power of music in Clive’s life cannot be overstated. It’s as if the melodies and rhythms bypass the damaged parts of his brain, allowing him to access a part of himself that remains untouched by his condition. This preservation of musical ability has opened up new avenues for therapy and rehabilitation for individuals with memory disorders.

As we look to the future, Clive Wearing’s case continues to inspire new directions in memory and consciousness studies. Researchers are exploring innovative techniques to enhance memory formation and retrieval, drawing on the lessons learned from Clive and others like him. It’s an exciting time in neuroscience, with each discovery bringing us closer to unraveling the mysteries of the mind.

In conclusion, Clive Wearing’s case serves as a powerful reminder of the complexity of human memory and the resilience of the human spirit. It challenges us to reconsider our understanding of consciousness, identity, and the very nature of experience. As we continue to explore the frontiers of memory research, we carry with us the invaluable lessons learned from Clive’s extraordinary journey.

Clive Wearing’s story is not just a tale of loss, but one of endurance, love, and the indomitable human spirit. It reminds us that even in the face of profound challenges, there is always room for hope, discovery, and the sweet melodies that connect us to our deepest selves.

References:

1. Baddeley, A., Aggleton, J., & Conway, M. (2002). Episodic Memory: New Directions in Research. Oxford University Press.

2. Sacks, O. (2007). The Abyss: Music and Amnesia. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/09/24/the-abyss

3. Wilson, B. A., & Wearing, D. (1995). Imprisoned in the present: What does amnesia tell us about the self? In A. Ellis & A. Young (Eds.), Human cognitive neuropsychology: A textbook with readings (pp. 477-497). Psychology Press.

4. Squire, L. R., & Wixted, J. T. (2011). The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 34, 259-288.

5. Wearing, D. (2005). Forever Today: A Memoir of Love and Amnesia. Doubleday.

6. Rosenbaum, R. S., Köhler, S., Schacter, D. L., Moscovitch, M., Westmacott, R., Black, S. E., … & Tulving, E. (2005). The case of K.C.: contributions of a memory-impaired person to memory theory. Neuropsychologia, 43(7), 989-1021.

7. Corkin, S. (2013). Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, H.M. Basic Books.

8. Eichenbaum, H. (2013). Memory on time. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(2), 81-88.

9. Wilson, B. A., Baddeley, A. D., & Kapur, N. (1995). Dense amnesia in a professional musician following herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 17(5), 668-681.

10. Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 1-25.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Schizophrenia Brain: Neurological Insights and Comparisons

Schizophrenia Brain Abnormalities: Mapping the Neurological Landscape

Schizophrenia’s Impact on the Brain: Structural and Functional Changes

Brain Reservoir: Unlocking the Hidden Potential of Neural Plasticity

Brain Tumors and Schizophrenia: Exploring the Potential Connection

Anoxic Brain Injury Treatment: Comprehensive Approaches for Recovery

Scripps Brain Injury Program: Comprehensive Care for Neurological Recovery

Sensory Overload After Brain Injury: Causes, Symptoms, and Coping Strategies

Sensitive Brain Symptoms: Recognizing and Managing Neurological Hypersensitivity

Orrin Cyborg Brain Scan: Revolutionizing Neurotechnology and Human-Machine Interfaces

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Musical memory in a patient with severe anterograde amnesia

Sara cavaco, justin s feinstein, henk van twillert, daniel tranel.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Authors contributed equally

Issue date 2012.

The ability to play a musical instrument represents a unique procedural skill that can be remarkably resilient to disruptions in declarative memory. For example, musicians with severe anterograde amnesia have demonstrated preserved ability to play musical instruments. However, the question of whether amnesic musicians can learn how to play new musical material despite severe memory impairment has not been thoroughly investigated. We capitalized on a rare opportunity to address this question. Patient SZ, an amateur musician (tenor saxophone), has extensive bilateral damage to his medial temporal lobes following herpes simplex encephalitis, resulting in a severe anterograde amnesia. We tested SZ’s capacity to learn new unfamiliar songs by sight-reading following three months of biweekly practices. Performances were recorded and then evaluated by a professional saxophonist. SZ demonstrated significant improvement in his ability to read and play new music, despite his inability to recognize any of the songs at a declarative level. The results suggest that it is possible to learn certain aspects of new music without the assistance of declarative memory.

Introduction

Patients with dense amnesia due to bilateral medial temporal lobe damage ( Wilson, Baddeley, & Kapur, 1995 ; Anderson et al., 2007 ) or due to dementia of the Alzheimer’s type ( Schacter, 1983 ; Beatty et al., 1988 , 1994 , 1999 ; Crystal, Grober & Masur, 1989 ; Cowles et al., 2003 ; Fornazzari et al., 2006 ; for a review see Baird & Samson, 2009 ) have demonstrated a remarkable ability to continue to perform certain types of activities that they learned prior to brain injury (e.g., driving, playing a musical instrument, and playing golf). The ability to learn and retain new perceptual or motor skills (e.g., rotary pursuit, mirror-tracing, and mirror-reading) and the ability to learn new habits (e.g., probabilistic-learning) are also known to be intact in amnesic patients (e.g., Milner, 1962 ; Cohen & Squire, 1980 ; Gabrieli, Corkin, Mickel, & Growdon, 1993 ; Tranel, Damasio, Damasio, & Brandt, 1994 ; Hay, Moscovitch & Levine, 2002 ; Cavaco, Anderson, Allen, Castro-Caldas & Damasio, 2004 ). Cohen and Squire (1980) found that amnesic patients were able to acquire the mirror reading skill at a normal rate despite poor memory for the words that they had read. This dissociation led these authors to distinguish between declarative forms of memory (dependent on the medial temporal lobe system), and procedural, nondeclarative forms of knowledge which are often spared in amnesic patients. Declarative memory refers to the capacity for conscious recollection about facts and events, whereas nondeclarative memory is expressed through performance rather than recollection ( Squire, 2004 ). Nondeclarative memory includes different forms of learning and memory abilities, including the perceptual and motor skills involved in musical performance. Even though some aspects of the musical performance can be declared, the actual skills are often carried into action without conscious retrieval of information regarding the procedural aspects of music.

Understanding how the brain processes music and how music can help neurological patients heal and overcome adversity is a rapidly growing field of study ( Levitin, 2007 ; Sacks, 2008 ). A series of case reports have described patients with significant declarative memory impairments who can still play musical instruments somewhat skillfully ( Beatty et al., 1988 , 1994 , 1999 ; Crystal et al., 1989 ; Wilson et al., 1995 ; Beatty, Brumback, & Vonsattel, 1997 ; Baur, Uttner, Ilmberger, Fesl & Mai, 2000 ; Cowles et al., 2003 ; Fornazzari et al., 2006 ). All of these reports describe instances of amnesic musicians who are able to perform songs that they had learned how to play prior to the onset of their amnesia. Perhaps the most well-known of these cases is Clive Wearing, a renowned musicologist with severe amnesia after sustaining bilateral medial temporal lobe damage due to herpes simplex encephalitis ( Wilson et al., 1995 ). According to the authors, Clive demonstrated an intact ability to “sight-read, obey repeat marks within a short page, and understand the significance of a metronome mark… ornament, play from a figured bass, transpose, and extemporize.” This description of Clive’s musical skills was the first non-neurodegenerative evidence of relatively preserved ability to perform a musical instrument despite severe multi-modal declarative memory impairment. It is currently unknown, however, whether or not Clive is able to learn how to play new songs.

Two early case reports described attempts to teach unfamiliar songs to piano players with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type; one by sight-reading ( Beatty et al., 1988 ) and the other by ear ( Beatty et al., 1999 ). Even though both patients were able to play familiar songs that had been learned premorbidly, their ability to learn a new composition was rather limited. However, the patients’ significant non-amnestic cognitive impairments may have hampered their ability to engage with the training process. Cowles and colleagues (2003) later described the case of a moderately demented patient with probable Alzheimer’s disease who was able to play a new song on the violin and demonstrated some limited capacity to play parts of the song by request (i.e., playing without sheet music) at delays of 0 and 10 minutes. The attempts to cue the patient’s performance by providing the first measures of the new song were found unsuccessful. Fornazzari and colleagues (2006) assessed the ability of a professional pianist with probable Alzheimer’s disease to learn unfamiliar musical pieces and observed “gradual improvements in overall performance and in rhythm, field elements, harmony, melodic accuracy, and sophistication in the accompaniment of the left hand” over a seven day period. However, the authors did not provide any quantification of the improvements. Baur and colleagues (2000) described a herpes simplex encephalitis patient (CH) who learned how to play the accordion, autodidactically, after the onset of her amnesia. Patient CH did not have any premorbid sight-reading training nor did she have any experience of playing a musical instrument. Yet, remarkably, she was able to learn how to play 90 pieces of Austrian and German folk music after listening to the songs on the radio or on tape. Moreover, she was able to play a song when cued with the song title, and she was also able to provide the song title when cued with a recording of the music. This suggests that CH had preserved declarative memory for the music, despite her overall poor performance on a battery of standardized memory tests. Thus, at least some of CH’s intact ability to learn new music could be explained by her reservoir of preserved declarative memory for music. Taken together, the results of the five aforementioned case studies are mixed. Two of the Alzheimer’s patients were unable to learn new music, whereas two other Alzheimer’s patients showed some residual learning. In addition, the findings in encephalitic patient CH are confounded by the patient’s ability to learn new declarative information about music.

To date, then, available research does not provide a definitive conclusion about whether the ability to learn and play unfamiliar music can be preserved in the context of a severe impairment in declarative memory. Here, we explored the capacity of an amateur musician, who had dense multi-modal anterograde amnesia, to perform and learn a series of new songs after three months of intense practice.

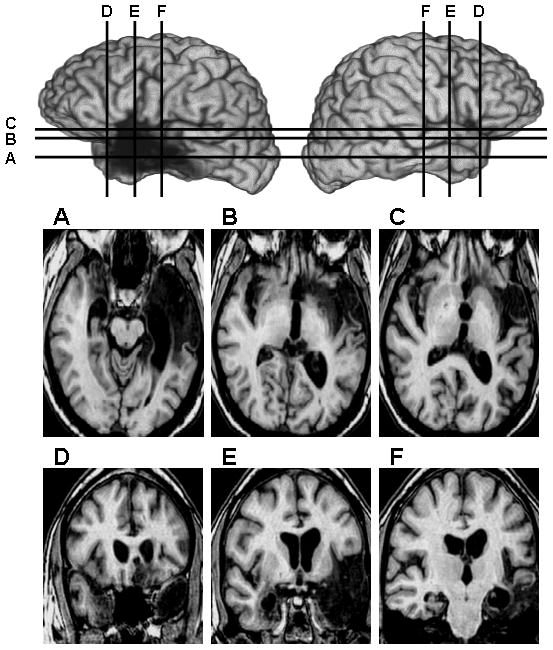

Patient SZ is a 51-year-old, fully left-handed man (-100 on the modified Geschwind-Oldfield Handedness Questionnaire) with 16 years of education and a bachelor’s degree in engineering. He had a normal developmental history and no neurologic problems until developing herpes simplex encephalitis at age 42. SZ’s MRI scans reveal large bilateral lesions affecting the hippocampus, amygdala, temporal poles, and insular cortices ( Figure 1 ). The damage is more extensive in the left hemisphere, completely destroying the hippocampus, amygdala, temporal pole, adjacent sectors of the anterior temporal lobe, and most of the insular cortex, especially the anterior portion. In addition, the left hemisphere damage extends anteriorly into the basal forebrain and posterior surface of the orbitofrontal cortex. In the right hemisphere, the damage is not as severe and is largely circumscribed to the medial temporal lobe, medial temporal pole, and insular cortex.

Figure 1. MRI scans of patient SZ’s brain.

Lateral views of the left hemisphere (left) and right hemisphere (right) are shown in the upper section of the figure, and axial (A–C, middle row) and coronal (D–E, bottom row) slices are shown below. (A) Axial slice depicting bilateral damage to the medial temporal lobe, medial temporal poles, and unilateral damage to a large region of the left temporal lobe. (B & C) Axial slices depicting bilateral damage to the insular cortex and left-sided damage to the basal forebrain and posterior orbitofrontal cortex. (D) Coronal slice depicting bilateral damage to the temporal poles (with only the medial temporal pole affected on the right side), and unilateral damage in the region of the left basal forebrain. (E) Coronal slice depicting bilateral damage to the amygdala and insula, and unilateral damage to a large region of the left temporal lobe. (F) Coronal slice depicting bilateral hippocampal damage and some damage to the left temporal cortices and left posterior insula. All images use radiological convention (i.e., right side of image = left hemisphere and vice versa).

On the neuropsychological evaluation ( Tranel, 2009 ), SZ revealed a profound anterograde amnesia ( Table 1 ). He was unable to recall or recognize any declarative information, verbal or visual, even after repeated presentations. Despite his severe declarative memory impairment, SZ has shown relatively preserved premorbid driving abilities (participant #2 in Anderson et al., 2007 ) and has demonstrated normal ability to acquire and retain a series of new perceptual-motor skills (subject #2 in Cavaco et al., 2004 ), suggesting intact procedural memory. Likewise, he also demonstrated intact performances on measures of working memory. His overall general intellectual functioning falls in the low average range, somewhat below expectations given his educational background. Some of his IQ scores were artificially reduced by his inability to remember the task instructions and his slowed processing speed. However, when examining specific measures that are known to be good indicators of premorbid intellectual functioning (e.g., reading ability, vocabulary, similarities, and matrix reasoning) his scores are in the average to above average range, well within normal expectations. His block design score and arithmetic achievement score are below expectations given his engineering background, a finding which might be partially related to the time constraint imposed by both tests that negatively affected his performance due to his slowed processing speed and poor memory for the task instructions. SZ’s basic language functioning, including naming and comprehension, is preserved (likely due to his left-handedness) despite extensive damage to critical language areas in the left hemisphere. His speech is fluent, well-articulated, and nonparaphasic, with normal rate, volume, and prosody. He does have a tendency to perseverate during conversations, often times repeating the same phrases multiple times. Additionally, he performed poorly on a test of verbal associative fluency. His basic visuospatial, visuoperceptual, and visuoconstructional abilities are mostly intact, although, once again, his slowed processing speed and tendency to forget task instructions at times adversely affected his test performance. He reported no signs of any depression or anxiety. He displayed a normal range of affect, including laughter and irritability. His anger is usually triggered by situations where he feels his independence is being hindered or his intelligence is being questioned. SZ displays a profound lack of awareness for his memory impairment (i.e., anosognosia), and will typically deny having any problems, or even weaknesses, in the domain of memory.

Neuropsychological evaluation

Scores are presented in standard/scaled scores (*) or as raw scores (**). The WAIS-III subtest scores are age-corrected scaled scores. The z-scores were calculated with reference to demographically matched normative samples ( Tranel, 2009 ). Results that are below expectations or that are defective in comparison to demographically matched normative samples are marked with an X (i.e., scores greater than 2 standard deviations from the normative mean).

Musical experience

SZ received musical training on his saxophone between the ages of 12 and 18. In high school, SZ played in a jazz band that at one time competed at the national level and won the second place prize. After graduating from high school, he stopped playing the saxophone and did not resume playing until three years after his brain injury (i.e., over 27 years later). Both of SZ’s parents stated that they were impressed with how seamlessly he was able to play the saxophone again after such a long hiatus. For the past six years, SZ has been playing in an amateur orchestra. The conductor considers him an average saxophonist, rating him a 5 on a 10 point scale when compared to the other members of the orchestra (all of whom are healthy and without any notable memory problems or brain damage). According to the conductor, SZ is a good sight-reader and his main difficulties are maintaining a consistent tempo and staying in time with the band. The conductor stated that while most members of the orchestra tend to fall behind when playing, SZ tends to play too fast. Additionally, SZ will often skip repeat signs while reading sheet music. Consequently, no one has ever observed SZ enter into a never-ending loop, where he would continuously repeat a section of a song, forgetting each time that he had already repeated that same section. In order to reduce his rapid playing tempo and make sure he properly follows repeat signs, SZ’s mother accompanies him to all practices and concerts, and helps him follow along on the sheet music. An interesting feature of SZ’s personality and playing style is that he will only play music on his saxophone when provided with sheet music. He claims that he is unable to “play by ear” and consistently refuses any request to improvise a song or complete a song when cued or primed with the beginning notes. The one exception to this rule is his warm-up song, “Windy”, which he knows by heart and will routinely and spontaneously play without any sheet music. Of note, this song was written in 1967 by The Associations, over three decades before the onset of his brain injury.

In terms of music preferences, SZ stated that he likes “all styles” of music and has no particular preference. He often says, “music is the universal language… for children of all ages.” Interestingly, since his brain injury, music has become part of his identity. When asked about his dream job, he replied that he would like to be “a professional musician.” Moreover, he has stated that “music is empowering” and brings him immense joy in life. Both of his parents agree with this sentiment and have observed that music has a calming effect on SZ’s mood and has helped reduce occurrences of agitation and irritability.

Several anecdotes vividly illustrate the severity of SZ’s memory impairment while playing music. One example occurred at the end of a concert that SZ and his orchestra performed in front of an audience of approximately 500 people. A few minutes after the show was over, the audience congregated in the concert hall’s main entrance, waiting for the musicians to join them for a post-concert celebratory reception. One of the study’s co-investigators (J.S.F) approached SZ and inquired about when the concert would start. SZ, completely unaware that he and his orchestra had just finished performing a nearly 2-hour long concert, replied, “I think we’ll probably start here in a few minutes.” In a previous unpublished experiment, SZ was asked to play the song, “You Raise Me Up” (as performed by Josh Groban) eight consecutive times in a 22-minute period, taking a 30–60 second break in between each rendition. At the beginning and end of each of the 8 trials, SZ was asked whether he recognized the song and whether he had played the song before. In all cases, he denied having seen or played the song before. His amnesia was so dense that he would forget having played the song within a mere 30 seconds of completion. Of note, the song “You Raise Me Up” was written after the onset of his amnesia. This particular version was contained on one page of sheet music and could be played in approximately two minutes. Thus, even with a massive amount of exposure over a short period of time, SZ was unable to remember the music.

Informed written consent was obtained from SZ and his family prior to participating in the study. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. The conductor of SZ’s orchestra provided us with the sheet music (11 songs in total) that the orchestra would be learning once they returned from a holiday period. These 11 songs comprised our target condition. Based on his parents report, SZ had never seen nor played any of the target songs at anytime in his life. We also included sheet music for 5 control songs, all of which were only played during the testing sessions (i.e., he never practiced or played these songs in-between testing sessions). Blinded to the stimulus condition, the expert rater (author H.v.T.) classified the songs from 1 to 10, according to its level of difficulty for an amateur musician ( Table 2 ).

Play list and assessment results comparing change from Time 1 to Time 2

Assessment results (−) Time 2 < Time 1; (+) Time 2 > Time 1; (=) Time 2 = Time 1.

SZ’s musical performances were recorded during two separate testing sessions (time 1 and time 2) separated by 100 days. Time 1 occurred one week before the orchestra started rehearsing. Time 2 occurred after three months of continuous rehearsals during which the orchestra met twice a week for at least one hour per rehearsal. In total, SZ practiced the target songs for at least 30 hours between time 1 and time 2. During each testing session, SZ performed 16 different songs in a room by himself (i.e., without the orchestra). All songs were played by sight-reading using sheet music. The songs were presented in the same order each time (see Table 2 ). At the beginning of each song, the examiner presented SZ with the sheet music and asked him whether he recognized the name of the song and whether he remembered having played the song before. SZ then proceeded to play the song using a tenor saxophone (key of B b ). All performances were recorded using a digital audio recorder.

Each song was judged by a professional saxophonist (author H.v.T.; http://www.saxunlimited.com ) who was blinded to both the song order (i.e., before versus after three months of practice) and type of song (i.e., target versus control song). SZ’s performances at time 1 and time 2 were rated on five different measures (intonation, sound quality, rhythmic awareness, notes awareness, and overall sight-reading accuracy). All ratings were provided on a 10-point scale with 0 being extremely poor performance and 10 being an adequate performance for an amateur musician. Intonation corresponds to the pitch accuracy between played intervals (with A=440Hz as reference). Sound quality depends on the flow of air and the pressure on the mouthpiece. Rhythmic awareness refers to the correct identification of the notated rhythm and the immediate correction when the duration of sound does not correspond to what is expected. Notes awareness refers to the correct identification of the written notes and the immediate correction when the sound does not correspond to what is expected based on the sheet music. The overall sight-reading accuracy refers to compliance with the sheet music instructions regarding: notes, rhythm, and tempo (e.g., Adagio-slow, Allegro-fast, Presto-very fast), dynamics (e.g., PP-very soft, FF-very loud, crescendo-get gradually louder, decrescendo-get gradually softer), and repeat signs.

Declarative memory

SZ did not recognize any of the target or control songs at time 1 or time 2. In all cases, he completely denied having any memory or recognition for the song. The one exception was target song #7, “If Thou Be Near” by Bach. In both testing sessions, he recognized the name Bach on the sheet music and claimed that he “thinks” he has played the song before. As previously stated, both of his parents claim that he never played any of the target songs prior to Time 1. Therefore, we believe that his claim for recognizing this particular song is purely due to his recognition of the composer.

Musical performance

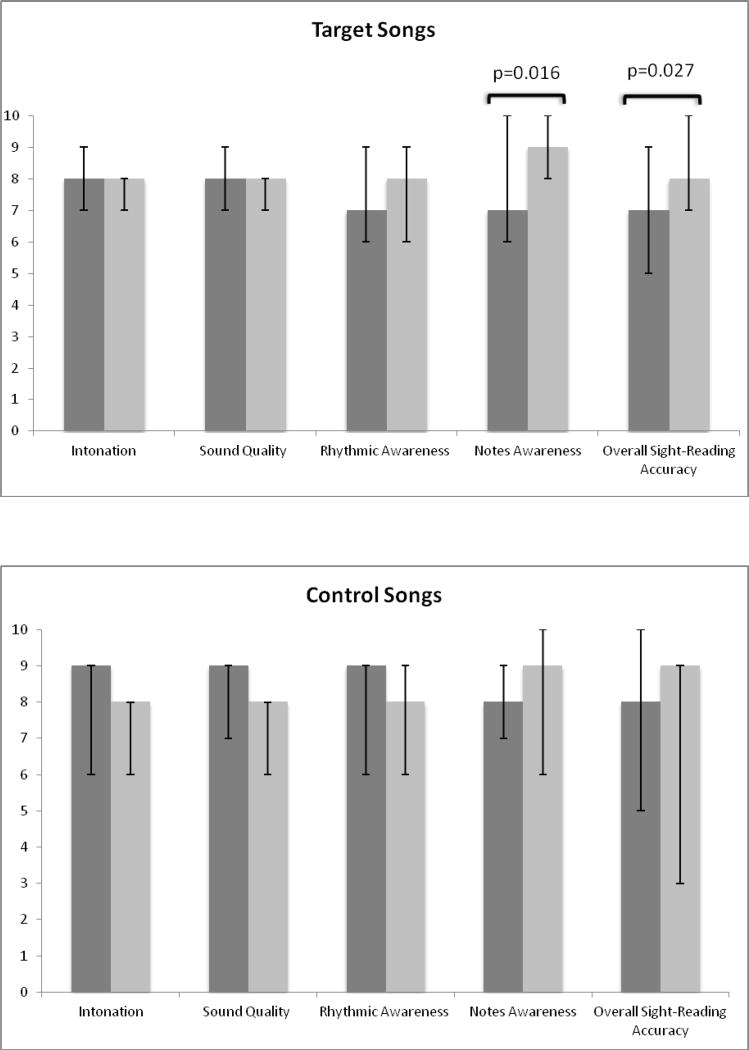

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the performance on the target songs and the control songs at time 1 (i.e., before he had any practice playing the target songs). No significant differences (p>0.05) were found on any of the five measures ( Figure 2 ). Additionally, there were no significant differences (Mann-Whitney U=27; p=0.954) on the level of difficulty between the target (median=4; mean rank=8.5) and the control (median=4.5; mean rank=8.6) songs ( Table 2 ).

Figure 2. SZ’s performance on the Target and Control songs at Time 1 and Time 2.

The results are presented as median scores. The error bars represent the range between minimum and maximum scores. Time 1 corresponds to dark grey bars and Time 2 to the light grey bars. No significant differences were found between target and control songs at Time 1 on any of the measures. SZ’s performance improved significantly on the target songs from Time 1 to Time 2, as measured by Notes Awareness and Overall Sight-Reading Accuracy indices. His performance on the control songs did not change significantly from Time 1 to Time 2.

SZ demonstrated improvement from Time 1 to Time 2 on notes awareness (for 7/11 target songs) and overall sight-reading accuracy (for 6/11 target songs), and neither of these measures showed any decline over time for any of the target songs (see Table 2 for a song by song breakdown). Positive changes over time were also found on intonation (1/11), sound quality (3/11), and rhythmic awareness (6/11). For the control songs, positive changes over time were found on notes awareness (for 4/5 control songs), overall sight reading accuracy (2/5), intonation (1/5), sound quality (1/5), and rhythmic awareness (1/5).

The Wilcoxon test for paired samples was applied to compare the expert’s scoring of each song at time 1 and time 2. According to the professional musician’s evaluation, after three months of intense exposure to the music during biweekly orchestra practices, patient SZ demonstrated significant improvement on the performance of the target songs, as measured by notes awareness (median=7 at Time 1 and median=9 at Time 2; mean of the negative ranks=0; mean of the positive ranks=4; Z=−2.414, p=0.016, r =−0.51) and overall sight-reading accuracy (median=7 at Time 1 and median=8 at Time 2; mean of the negative ranks=0; mean of the positive ranks=3.5; Z=−2.214, p=0.027, r =−0.47;) ( Figure 2 and Table 2 ). No significant improvements were found on the other measures (i.e., intonation, sound quality, and rhythm awareness).

The comparisons between time 1 and time 2 for the control songs did not reveal any significant changes. For three indices (intonation, sound quality, rhythmic awareness), his performance on the control songs was numerically lower at Time 2; this never occurred on the target songs. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the level of difficulty of the songs that showed improvement versus those that did not. No significant difference (p>0.05) was found.

Patient SZ showed significant improvement when learning a series of new unfamiliar songs over a three-month period of intensive training despite his complete inability to consciously remember having played any of the music. The learning was confined to measures tapping into perceptual-motor aspects of saxophone playing, including notes awareness and sight-reading accuracy. In essence, he demonstrated content specific sight-reading improvements such that his ability to read musical notations on sheet music and translate these notations into movements became more accurate for the practiced songs.

Different brain regions have been shown to play a role in the perceptual-motor aspects of music. For example, playing a musical instrument by sight-reading has been found to activate the superior parietal cortex, bilaterally, both in professional musicians ( Sergent, Zuck, Terriah & MacDonald, 1992 ) and in musically-naive individuals after training ( Stewart et al., 2003 ). The basal ganglia and the cerebellum have been found to be engaged in the performance of a memorized musical composition by blindfolded pianists ( Parsons , Sergent, Hodges, & Fox, 2005 ). Human lesion studies have also implicated these brain regions in the acquisition of new perceptual and motor skills (e.g., Laforce & Doyon, 2001 ; Cavaco et al., 2011 ). High-resolution MRI images clearly indicate that the superior parietal cortex, the basal ganglia, and the cerebellum are not damaged in SZ, and thus, may be contributing to his improved musical performance on perceptual-motor aspects of learning.

While SZ demonstrated significant learning on perceptual-motor aspects of music, the effect was modest in size. The professional musician that scored his performance speculated that most of his students would have shown a much greater improvement (compared to SZ) if they had repeatedly practiced the material over a three month time period. However, the present study was not designed to ascertain whether the magnitude of SZ’s learning was within or below the “normal” range. The normality of learning, vis-à-vis whether a patient with severe anterograde amnesia is capable of learning to perform new music at a normal rate, is a completely separate issue from whether any new musical learning can take place in such a patient. The absence of a healthy “control” group narrows the scope of the discussion, but does not compromise the main finding — the contrast between SZ’s learning to play new music, and his inability to remember the music at a declarative level is clear and robust.

The assessment of SZ’s learning may have been altered due to the testing environment, which differed substantially from his practice environment with his orchestra. Since on both testing sessions SZ played the saxophone by himself, it is unclear whether his performance would be enhanced when playing with the full orchestra. Notably, the training of the target songs was accomplished in the context of orchestra practice. During this training, SZ received extra visual and auditory cues from the conductor, his mother, and the other musicians in the orchestra. These immediate external references may have facilitated better pitch correction and rhythmic awareness, and this is certainly something that can be tested in a future study. Non-declarative knowledge has been suggested to be essentially inflexible and non-relational, and the expression of this type of memory is potentiated when the conditions at the assessment mirror the original learning conditions ( Cohen, Poldrack & Eichenbaum, 1997 ). Additionally, SZ’s training process did not avoid the occurrence of errors. Error elimination is known to be particularly problematic in amnesic patients ( Baddeley & Wilson, 1994 ). In the absence of declarative (explicit) recollection of prior training experiences, an amnesic patient tends to make the same errors over and over. It is reasonable to speculate that a longer training period, individually tailored and based on an errorless approach, would have produced better learning results in SZ.

The piecemeal improvement in SZ’s musical memory is likely to reflect the complexity of cognitive processes necessary to learn a new musical piece. The acquisition, integration, and retrieval of both declarative and non-declarative knowledge are all part of the musical learning process. Healthy musicians benefit from the conscious recollection of prior exposure to a particular song. With repeated exposure, a normal musician tends not to read all the written information on a piece of sheet music, but rather, develops a “feel” for the song’s progression and over time develops a “muscle memory” for the song itself. This combination of declarative and procedural learning may contribute to more efficient eye-hand spans (i.e., the separation between eye position and hand position when sight-reading music; Furneaux & Land, 1999 ), and subsequently to better and smoother performances.

SZ did not show significant improvement on some of the indices, namely sound quality, intonation, and rhythmic awareness. The sound quality of a musician is a relatively stable non-declarative skill, i.e., it is less dependent on content specific training than all the other measures and significant changes are more likely to require extensive training. Intonation and rhythmic awareness are partially related to a musician’s ability to convey the emotional undertone or “prosody” of the song’s melody in such a manner that the timing and inflection of each note seamlessly merges with the subsequent note, creating a coherent musical piece that conveys a distinct “feeling.” When SZ’s music recordings were played to professional and amateur musicians, those listeners commented that the sound was somewhat “robotic” or “machine-like” in nature. SZ’s basic perception of music and his processing of emotions in musical stimuli were not explored. Likewise, we did not specifically measure whether SZ’s saxophone playing is generally “flat” with regard to emotion for all music that he plays. However, there are indications that he is able to convey at least some emotion while playing the saxophone. During his warm-up song, “Windy,” the sound was much more vibrant and filled with emotion. Likewise, during testing, all measures were above the floor (see Figure 2 ) suggesting that at least some aspects of emotion were present when he played the saxophone. Future studies examining the learning of new musical material in amnesic patients could consider using experimental designs with similar assessment and training conditions, multiple expert raters, and the inclusion of foil excerpts for the raters (i.e., clips played by different musicians interspersed with those played by the patient).

In summary, the ability to play a musical instrument represents a unique procedural skill that appears to be resilient to disruption of declarative memory. Previous studies have not answered definitively the question of whether amnesic musicians are capable of learning new music. The present study capitalized on a rare opportunity to address this issue by exploring the capacity to learn new songs in an amateur musician with severe non-progressive anterograde memory impairment. The patient’s performance, before and after three months of prolonged exposure and practice, highlighted the distinction between some preserved capacity to acquire non-declarative memories for new musical material and the complete inability to learn any declarative information about the songs. The magnitude of this new learning was relatively modest and appeared to be confined to the perceptual-motor aspects of playing new music.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to SZ and his family for their unwavering support and continued commitment to brain research. We also would like to thank SZ’s caregivers and his orchestra for allowing us to observe. Nicolau Pinto Coelho, Mikiko Kanemitsu, Gilberto Bernardes, and Fernando Ramos provided important musical expertise, Kenneth Manzel contributed with the neuropsychological evaluation, and Steven W. Anderson provided invaluable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This research was supported by NIH P50 NS19632 and the Kiwanis Foundation.

- Anderson SW, Rizzo M, Skaar N, Stierman L, Cavaco S, Dawson J, et al. Amnesia and driving. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13803390590954182. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baddeley A, Wilson BA. When implicit learning fails: amnesia and the problem of error elimination. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:53–68. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90068-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baird A, Samson S. Memory for music in Alzheimer’s disease: Unforgettable? Neuropsychological Review. 2009;19:85–101. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9085-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baur B, Uttner I, Ilmberger J, Fesl G, Mai N. Music memory provides access to verbal knowledge in a patient with global amnesia. Neurocase. 2000;6:415–421. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Brumback RA, Vonsattel JP. Autopsy-proven Alzheimer disease in a patient with dementia who retained musical skill in life. Archives of Neurology. 1997;54:1448. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240008002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Zavadil KD, Bailly RC, Rixen GJ, Zavadil LE, Farnham N, et al. Preserved musical skill in a severely demented patient. International Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1988;10:158–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Winn P, Adams RL, Allen EW, Wilson DA, Prince JR, et al. Preserved cognitive skills in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Archives of Neurology. 1994;51:1040–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540220088018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beatty WW, Rogers CL, Rogers RL, English S, Testa JA, Orbelo DM, et al. Piano playing in Alzheimer’s disease: Longitudinal study of a single case. Neurocase. 1999;5:459–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavaco S, Anderson SW, Allen JS, Castro-Caldas A, Damasio H. The scope of preserved procedural memory in amnesia. Brain. 2004;127:1853–1867. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh208. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavaco S, Anderson SW, Correia M, Magalhães M, Pereira C, Tuna A, et al. Task-specific contribution of the human striatum to perceptual-motor skill learning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011;33:51–62. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.493144. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen NJ, Squire LR. Preserved learning and retention of pattern analyzing skill in amnesia: dissociation of knowing how and knowing that. Science. 1980;210:207–209. doi: 10.1126/science.7414331. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen NJ, Poldrack RA, Eichenbaum H. Memory for items and memory for relations in the procedural/declarative memory framework. Memory. 1997;5:131–178. doi: 10.1080/741941149. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cowles A, Beatty WW, Nixon SJ, Lutz LJ, Paulk J, Paulk K, et al. Musical Skill in Dementia: A Violinist Presumed to Have Alzheimer’s Disease Learns to Play a New Song. Neurocase. 2003;9:493–503. doi: 10.1076/neur.9.6.493.29378. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crystal H, Grober E, Masur D. Preservation of musical memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1989;52:1415–1416. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.12.1415. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fornazzari L, Castle T, Nadkarni S, Ambrose M, Miranda D, Apanasiewicz, et al. Preservation of episodic musical memory in a pianist with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;66:610–611. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000198242.13411.FB. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Furneaux S, Land MF. The effects of skill on the eye-hand span during musical sight-reading. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B. 1999;266:2435–2440. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0943. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gabrieli JDE, Corkin S, Mickel SF, Growdon JH. Intact acquisition and long-term retention of mirror-tracing skill in Alzheimer’s disease and in global amnesia. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993;107:899–910. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.899. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hay JF, Moscovitch M, Levine B. Dissociating habit and recollection: evidence from Parkinson’s disease, amnesia and focal lesion patients. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:1324–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00214-7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laforce R, Doyon J. Distinct contribution of the striatum and cerebellum to motor learning. Brain & Cognition. 2001;45:189–211. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2000.1237. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levitin DJ. This is your brain on music. New York: Plume; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Milner B. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. Physiologie de L’Hippocampe, colloques internationaux. 107. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; 1962. Les troubles de la mémoire accompagnant des lésions hippocampiques bilatérales; pp. 257–272. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parsons LM, Sergent J, Hodges DA, Fox PT. The brain basis of piano performance. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:199–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.11.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sacks O. Musicophilia: Tales of music and the brain. New York: Random House; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schacter DL. Amnesia observed: remembering and forgetting in a natural environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:236–242. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.2.236. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sergent J, Zuck E, Terriah S, MacDonald B. Distributed neural network underlying musical sight-reading and keyboard performance. Science. 1992;257:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1621084. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Squire LR. Memory systems of the brain: a brief and current perspective. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2004;82:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.06.005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stewart L, Henson R, Kampe K, Walsh V, Turner R, Frith U. Brain changes after learning to read and play music. Neuroimage. 2003;20:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00248-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tranel D. The Iowa-Benton school of neuropsychological assessment. In: Grant I, Adams KM, editors. Neuropsychological assessment of neuropsychiatric disorders. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 66–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tranel D, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Brandt JP. Sensorimotor skill learning in amnesia: Additional evidence for the neural basis of nondeclarative memory. Learning and Memory. 1994;1:165–179. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson BA, Baddeley AD, Kapur N. Dense amnesia in a professional musician following herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1995;17:668–81. doi: 10.1080/01688639508405157. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (479.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Streams of Thought

Technologist, Thinker and Leader

Forever, the present – The case of Clive Wearing and the question of memory, identity, and love.

All of us have experienced moments in our lives when we couldn’t remember or recollect something from the past. That is normal. Depending on our attentiveness and capacity to form neural connections, memories either stick or don’t stick. But for the most part, we do recollect what we need to and can experience a sense of chronological continuity. In a normal human being, the autobiographical narrative or self or consciousness is more or less intact. We can connect our existence from one moment to another. We can retain enough of the memories generated from the sensory inputs to live life as a continuum, and not as discrete slices. If I am told where sugar is located in the kitchen, I can reach out for it a few hours later. If I have met someone and chatted for some time, I can recollect the person and the chatting, though not the specifics of the chat all the time. In other words, our memories, both episodic and contextual, form the core basis of our self. Without our ability to form memories, we fall into an ontological abyss, a perpetual state of discontinuity and a break in consciousness. Our ability to stitch memories together gives us a sense of time. Without it, time does not exist. Ask a person who has had an alcohol or a general blackout, they will tell you how time can slip through the cracks of consciousness. It is not a question of remembering something, there is just no “remembering” at all; that interval of time simply doesn’t exist, they were not conscious, there are no traces of that experience, that memory, to call it their own. The continuum is missing. All they can say is “I don’t know” — an absolute existential black hole, a state of splintered consciousness.

It is impossible for us, in whom the memory-generating parts of the brain are intact, to imagine a state where the brain loses such an ability. We all live with manageable gaps in recollection, short periods of amnesia here and there; but to lose or take away the very structure and process of memory is unimaginable. Neuroscience has studied many cases of extreme memory losses, but none more extreme than the case of the musicologist and conductor Clive Wearing. Clive was an intellectual colossus in the British western classical music scene of the 1960s and 70s. Handsome, charismatic, brilliant, he worked for the BBC organizing programs on the works of late renaissance composers and chapel choirs. He was a meticulous musician with a prodigious musical sense and aesthetics. In March 1985, Clive fell ill, running a high temperature with splitting headaches. His young wife Deborah, with whom Clive had fallen in love and got married eighteen months ago, called the doctors and solicited their opinion. They dismissed it as flu. Within a week, Clive’s condition deteriorated, and he had to be moved to the hospital. After running a series of tests, they diagnosed the fever to be an extremely rare case of the Herpes encephalitis virus. This virus usually lurks harmlessly in the bloodstream, but in some cases, it starts multiplying and manifests itself as flu. In Clive’s condition, however, this virus had taken its most virulent form. In about one in a million cases, the virus breaches the blood-brain barrier, enters the brain, and destroys critical parts. Clive’s brain scan revealed that the virus had penetrated his brain, and ravaged most parts of his memory-making and holding structures. The doctors, fortunately, were able to halt the spread of the virus and save his life, but they were late in preventing the irrevocable and irreversible damage already done to parts of the brain that dealt with memory. Within a couple of weeks, it was clear that Clive had completely lost his short-term memory and large tracts of the long-term memory. He was fated to live moment to moment, with no past, and no future.

Clive’s case is the worst case of Amnesia ever recorded. Nothing stuck in his brain. Sensory inputs bounced off his brain, leaving no trace whatsoever. His memory was wiped clean every few seconds, and every moment was a new awakening to consciousness for him. He retained no knowledge of any previous moment, or experience, or face, or event. He couldn’t recognize the place he lived in, the people he met, the food he ate, or his own previous actions. Each experience, each fact, was lost in an abyss. Time, in the sense we know and understand it, had stopped for Clive. In her beautifully written and remarkable 2005 memoir “Forever Today, a tale of love and Amnesia” Deborah Wearing, Clive’s wife wrote: “His ability to perceive what he saw and heard was unimpaired. But he did not seem to be able to retain an impression of anything beyond a blink. Indeed, if he did blink, his eyelids parted to reveal an (entirely) new scene”. Clive’s sensory perceptions were intact, but nothing was processed. For processing requires memory, and memory wasn’t available to him. During the initial months and years, Clive would constantly tell people, “You are the first person I have ever met. I am alive just now. I haven’t heard anything, seen anything, touched anything, smelled anything… It’s like being dead”. Clive’s language skills and semantic memory (which is an abstract memory of some event in the past, but not the specifics) improved over time, but he could never recall specifics — which is a must for consciousness and a sense of personal agency. The autobiographical self needs an ongoing sense of past and present, a collection of short and long-term memories, coalescing and re-coalescing together to generate selfhood, an operative agency to function in the world. In its absence, no experience can be truly owned, or willed, or initiated.

Miraculously though, despite the total loss of continuity, and any meaningful residue of memory, there are two things that Clive could do even without the knowledge or explicit memory of doing it. He could recognize Deborah, and his affection for her was overflowing and ecstatic. To those who witnessed Clive’s instant recognition of deborah, It is indeed a mystery, how Clive could connect with Deborah alone, when he had lost all other memories, including those of his children. The answer is hidden, the miracle of the human brain. Memory is not contained within a single part of the brain, it is spread across its intricate structures. Clive’s deep love for Deborah has perhaps made its way, and seared itself into the deeper emotional structures of the brain. Clive’s response to Deborah was visceral, a recognition that perhaps springs from the depths of his organic being, and not from the peripheries of episodic memory or rationality. In Jonathan Miller’s beautiful documentary of Clive made in 1989, the most touching scenes are those where a docile and irritated Clive, suddenly erupts into life on seeing Deborah, runs, and hugs her with such unconditional, irrepressible, and childlike love, as if, her presence has momentarily vindicated his thoughtful-less existence and given it a solid center, which he perpetually lacked. of course, Clive doesn’t remember any of this. Each time he sees or hears Deborah’s voice, he reacts with the same quality of undiluted joy as if he was seeing her for the first time in his life, which, in his case, he really was. In a strange yet marvelous and moving way, Clive’s love for Deborah is never in the past, or of the past, it is always now — fresh, spontaneous, total, and without any pretense. Which wife wouldn’t want to be loved in this manner by their husbands?

The other thing that remained intact in Clive was his musical sensibilities. Clive could play a musical score on the piano to perfection, even managing to improvise along the way. His musical memory was virtually unaffected by amnesia. Though he didn’t remember any score or the composer names, he could sight-read music, play out the melody. In Jonathan Miller’s documentary, one can see Clive conducting his choir in King’s Chapel. If we were unaware that Clive was affected by amnesia, it would be impossible for us to make out from the performance that he had any deficiency at all. Clive’s professional musical personality flowers in full bloom for the duration of the music. Of course, he doesn’t remember anything about the performance afterward, but as long as the music lasted, he was the music. The continuum that Clive tragically lost in his daily life due to amnesia is miraculously restored by music. The musical notes, played one after another, give his being a stream of continuity. It helps to string his life together, giving it a harmonic coherence, a sense of meaning in the present, that somehow transcends, and at the same time, fills the void the loss of memory has left behind.

Clive is seventy years old now, and Deborah is still the anchor of his life. In the intervening twenty-five years, Clive has filled hundreds of journals with brief entries on the time of his awakening, each minute, each hour, scoring out the previous entries because he never remembered writing them or owning them. These diaries are Clive’s means to hold on to his existence. Thousands of entries are there, asking Deborah to come soon -“ at the speed of light” — in Clive’s desperate and loving language. Over the years, his anxiety has lessened a little, and procedural memory has become stronger. He can now do simple things without the need to remember and know. The human brain is superiorly adaptive, and what is lost in one area, is compensated in some other. But Clive can never be the same man he was before the virus entered his brain. He will live out his life moment to moment, forever now and today.

I came across Clive’s case in Dr. Oliver Sack’s wonderful collection of essays titled “Musicophilia”. Since my illness a decade ago, I had firmly come to believe that any disease, deficiency or excess, cannot be separated from the person having it. Modern medicine has become very specialized and functional. We have learned more and more about less and less, and in the process, sometimes miss the forest for the trees. In 2013, almost accidentally, I came across Dr. Sack’s bestselling book “The Man who mistook his wife for a hat”. The essays in the book opened my eyes to a new way of looking at sickness. Since then, I have attempted to study and understand the human brain and the cognitive processes through writers who have made such topics accessible to an educated reader. Most of what we know about the human body is only through a study of diseases, losses, or excesses. The brain is no exception. When we have our memories intact, and go about our daily lives, cribbing and complaining, we don’t realize the tremendous unconscious work that happens each living moment within the human body to even simply keep us alive. In our busy lives filled with this and that, we don’t appreciate what it is like to have memories. When we come across a case like Clive’s, we tend to dismiss it as a sickness and carry on. But such an attitude misses the point. Severe amnesia can teach us about our identities and how we form them. It helps us reflect on those childish and often ill-advised counsel of self-help books and gurus who constantly tells us to “live in the present, and not in the past”. One cannot live in the present if there is no past. Our neurological system needs the sustenance and stimulus of our autobiographical memories to function in the world outside; in its absence, we are left in an existential void.

Nearly five years after reading about Clive in Dr. Sack’s book, last week, I read Deborah Wearing’s moving memoir. The book has been on my shelf for a couple of years now. Deborah writes realistically and with great insight into what it means to live with a man, who cannot remember his wife’s name for more than a few seconds; a man who bombards her with the same agitated questions over and over again twenty-four hours a day; a man who despite his extreme memory deficiency manages to remember her, and only her, and runs to her with all the emotions he has in his possession; a man who has forgotten almost everything about his past, including his marriage; a man who has no hope of ever being the man he was in his prime; and, more importantly, what it means to live empathetically, with a profound understanding of what it means to love someone. Deborah’s life and the love between Clive and her is sacred if the word sacred means that which is pure, unconditional, uncontaminated, and undiminished.

In a haunting sentence, that resonates long after we have closed the book, Deborah writes“ you could lose almost everything you know about yourself, and still be yourself”. The “Cliveness” of Clive was always there, even when he lost his memory. The inner core, that unique essence, of each person, acquired through a lifetime of experiences leaves a deeper mark and makes each one of us a unique individual, a persona that will shine through, in sickness or in health. We are, in essence, our memories, a self pieced together from the residue of sensory, emotional, and intellectual impressions.

Yours in mortality,

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- High School

- You don't have any recent items yet.

- You don't have any courses yet.

- You don't have any books yet.

- You don't have any Studylists yet.

- Information

Life Without Memory - The Case of Clive Wearing