How to Write the Perfect Body Paragraph

A body paragraph is any paragraph in the middle of an essay , paper, or article that comes after the introduction but before the conclusion. Generally, body paragraphs support the work’s thesis and shed new light on the main topic, whether through empirical data, logical deduction, deliberate persuasion, or anecdotal evidence.

Some English teachers will tell you good writing has a beginning, middle, and end, but then leave it at that. And that’s true—almost all good writing follows an introduction-body-conclusion format. But what no one seems to talk about is that the vast majority of your writing will be middle . That puts a lot of significance on knowing how to write a body paragraph.

Give paragraphs extra polish Grammarly helps you write your best Write with Grammarly

Don’t get us wrong—introductions and conclusions are crucial. They fulfill additional responsibilities of preparing the reader and sending them off with a lasting impression, which is why every good writer knows how to write an introduction and how to write a conclusion . But in terms of volume , body paragraphs comprise almost all of your work.

We explain precisely how to write a body paragraph so your writing has substance through and through. After all, it’s what’s on the inside that counts!

Structure of a body paragraph

Think of individual paragraphs as microcosms of the greater work; each paragraph has its own miniature introduction, body, and conclusion in the form of sentences.

Let’s break it down. A good body paragraph contains the following four elements, some of which you may recognize from our ultimate guide to paragraphs :

- Transitions: These are a few words at the beginning or end of a paragraph that connect the body paragraph to the others, creating a coherent flow throughout the entire piece.

- Topic sentence: A sentence—almost always the first sentence—introduces what the entire paragraph is about.

- Supporting sentences: These make up the “body” of your body paragraph, with usually one to three sentences that develop and support the topic sentence’s assertion with evidence, logic, persuasive opinion, or expert testimonial.

- Conclusion (Summary): This is your paragraph’s concluding sentence, summing up or reasserting your original point in light of the supporting evidence.

To understand how these components make up a body paragraph, let’s look at a sample from literary icon Kurt Vonnegut Jr. In it, he himself looks to other literary phenoms William Shakespeare and James Joyce. The following sample comes from Vonnegut’s essay “ How to write with style .” It’s a great example of how a body paragraph supports the thesis, which in this case is: To write well, “keep it simple.”

As for your use of language: Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. “To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story “Eveline” is this one: “She was tired.” At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

In this sample, Vonnegut demonstrates the four main elements of body paragraphs in a way that makes it easy to identify them. Let’s take a closer look at each.

As for your use of language:

Rather than opening the paragraph with an abrupt change of topic, Vonnegut uses a simple, even generic, transition that softy guides the reader into a new conversation. The point of transitions is to remove any jarring distractions when moving from one paragraph to the next. They don’t need to be complicated; sometimes a quick phrase like “on the other hand” or even a single word like “however” will suffice.

Topic sentence

Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound.

Here, Vonnegut puts forth his main point, that even the greatest writers sometimes use simple language to convey complex ideas—the thesis of this particular body paragraph.

Supporting sentences

“To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story “Eveline” is this one: “She was tired.”

To support his thesis, Vonnegut pulls two direct quotes from respected writers and then dissects the wording to support his initial claim. Notice how there are a few different sentences with each exploring their own points, but they all relate to and support the paragraph’s main thesis.

At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

Vonnegut ends the paragraph with a pithy statement claiming that complex language would have been less effective, reaffirming his central claim that great writers know simple language works best.

How to start a body paragraph

Often the hardest sentence to write, the first sentence of your body paragraph should act as the topic sentence, introducing the main point of the entire paragraph. Also known as the “paragraph leader,” the topic sentence opens the discussion with an underlying claim (or sometimes a question).

After reading the opening sentence, the reader should know, in no uncertain terms, what the rest of the paragraph is about. That’s why topic sentences should always be clear, concise, and to the point. Avoid distractions or tangents—there will be time for elaboration in the supporting sentences. At times you can be coy and mysterious to build suspense, opening with a question that ultimately gets answered later in the paragraph. Nonetheless, you should still reveal enough information to set the stage for the rest of the sentences.

More often than not, your first sentence should also contain a transition to bridge the gap from the preceding paragraph. Under special circumstances, you may also put a transition at the end of the sentence, but in general, putting it at the beginning is better for readability.

Don’t let transitions intimidate you; they can be quite simple and even easy to apply. Usually, a single word or short phrase will do the job. Just be careful not to overuse the same transitions one after another. To help expand your transitional vocabulary, our guide to connecting sentences collects some of the most common transition words and phrases for inspiration.

How to end a body paragraph

Likewise, the concluding sentence to your body paragraph holds extra weight. Because the reader takes a momentary pause at the end of each paragraph, that last sentence will “echo” just a bit longer in their minds while their eyes find the beginning of the next paragraph. You can take advantage of those extra milliseconds to leave a lasting impression on your reader.

In form, your concluding sentence should summarize the thesis of your topic sentence while incorporating the supporting evidence—in other words, it should wrap things up.

It’s useful to end on a meaningful or even emotional point to encourage the reader to reflect on what was discussed. Vonnegut’s conclusion from our sample makes a strong and forceful statement, invoking heartbreak (“break the heart”) and using absolute language (“no other words”). Powerful language like this might be too climactic for the supporting sentences, but in a conclusion, it fits perfectly.

How to write a body paragraph

First and foremost, double-check that your body paragraph supports the main thesis of the entire piece, much like the paragraph’s supporting sentences support the topic sentence. Don’t forget your body paragraph’s place in the greater work.

When it comes to actually writing a body paragraph, as always we recommend planning out what you want to say beforehand, which is a good reason to learn how to write an outline . Crafting a good body paragraph involves organizing your supporting sentences in the optimal order—but you can’t do that if you don’t know what those sentences will be!

A lot of times, your supporting sentences will dictate their own logical progression, with one naturally leading into the next, as is often the case when building an argument. Other times, you’ll have to make a choice about which evidence to present first and last, as Vonnegut did when choosing between his Shakespeare and Joyce examples. Also as with Vonnegut’s example, your choice of conclusion may help determine the best order.

This can be a lot of take in, especially if you’re still learning the fundamentals of writing. Luckily, you don’t have to do it alone! Grammarly offers suggestions beyond spelling and grammar, helping you hone clarity, tone, and conciseness in your writing. With Grammarly, ensure your writing is clear, engaging, and polished, wherever you type.

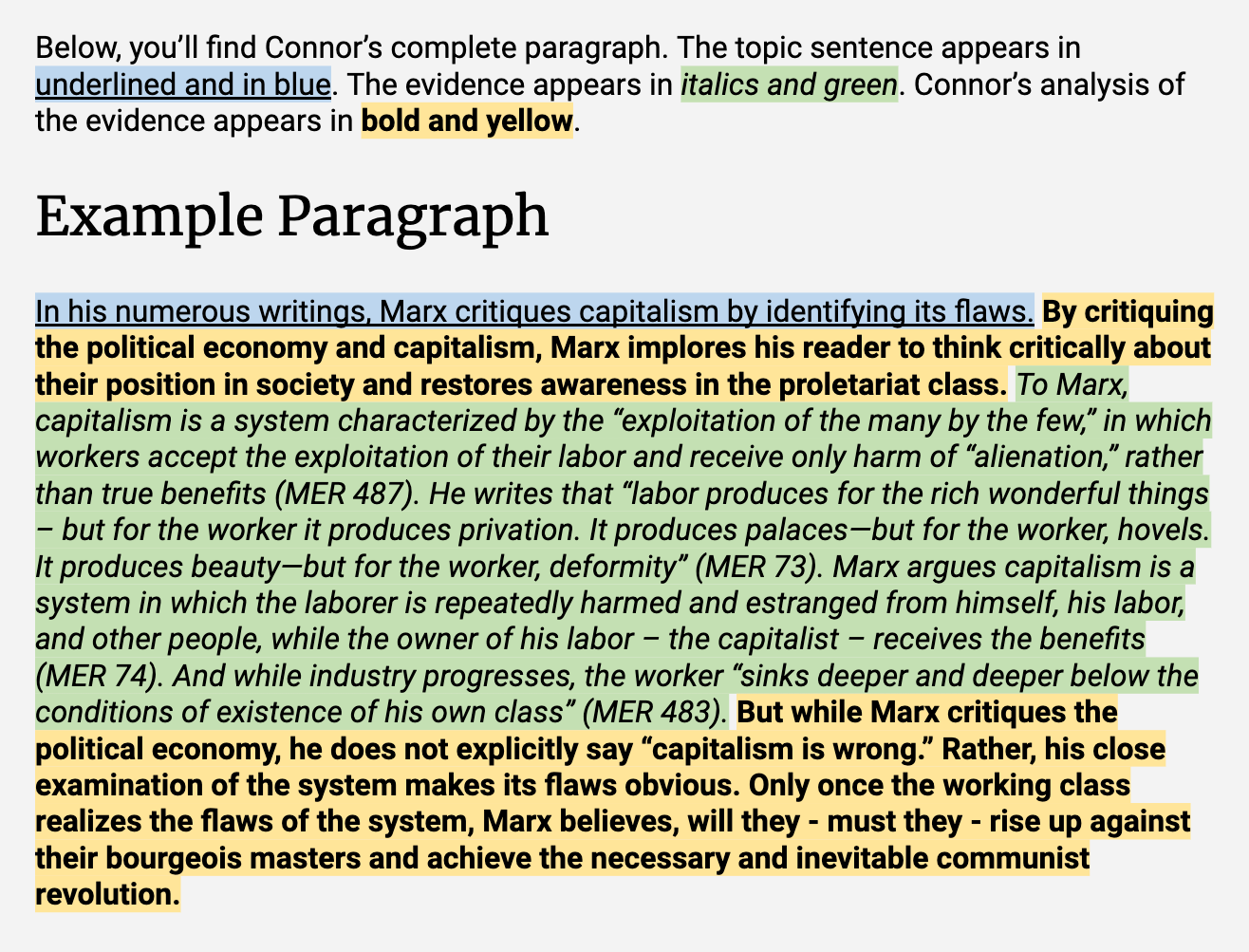

TOPIC SENTENCE/ In his numerous writings, Marx critiques capitalism by identifying its flaws. ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ By critiquing the political economy and capitalism, Marx implores his reader to think critically about their position in society and restores awareness in the proletariat class. EVIDENCE/ To Marx, capitalism is a system characterized by the “exploitation of the many by the few,” in which workers accept the exploitation of their labor and receive only harm of “alienation,” rather than true benefits ( MER 487). He writes that “labour produces for the rich wonderful things – but for the worker it produces privation. It produces palaces—but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty—but for the worker, deformity” (MER 73). Marx argues capitalism is a system in which the laborer is repeatedly harmed and estranged from himself, his labor, and other people, while the owner of his labor – the capitalist – receives the benefits ( MER 74). And while industry progresses, the worker “sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class” ( MER 483). ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ But while Marx critiques the political economy, he does not explicitly say “capitalism is wrong.” Rather, his close examination of the system makes its flaws obvious. Only once the working class realizes the flaws of the system, Marx believes, will they - must they - rise up against their bourgeois masters and achieve the necessary and inevitable communist revolution.

Not every paragraph will be structured exactly like this one, of course. But as you draft your own paragraphs, look for all three of these elements: topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Anatomy Of a Body Paragraph

How to write an essay: Body

- What's in this guide

- Introduction

- Essay structure

- Additional resources

Body paragraphs

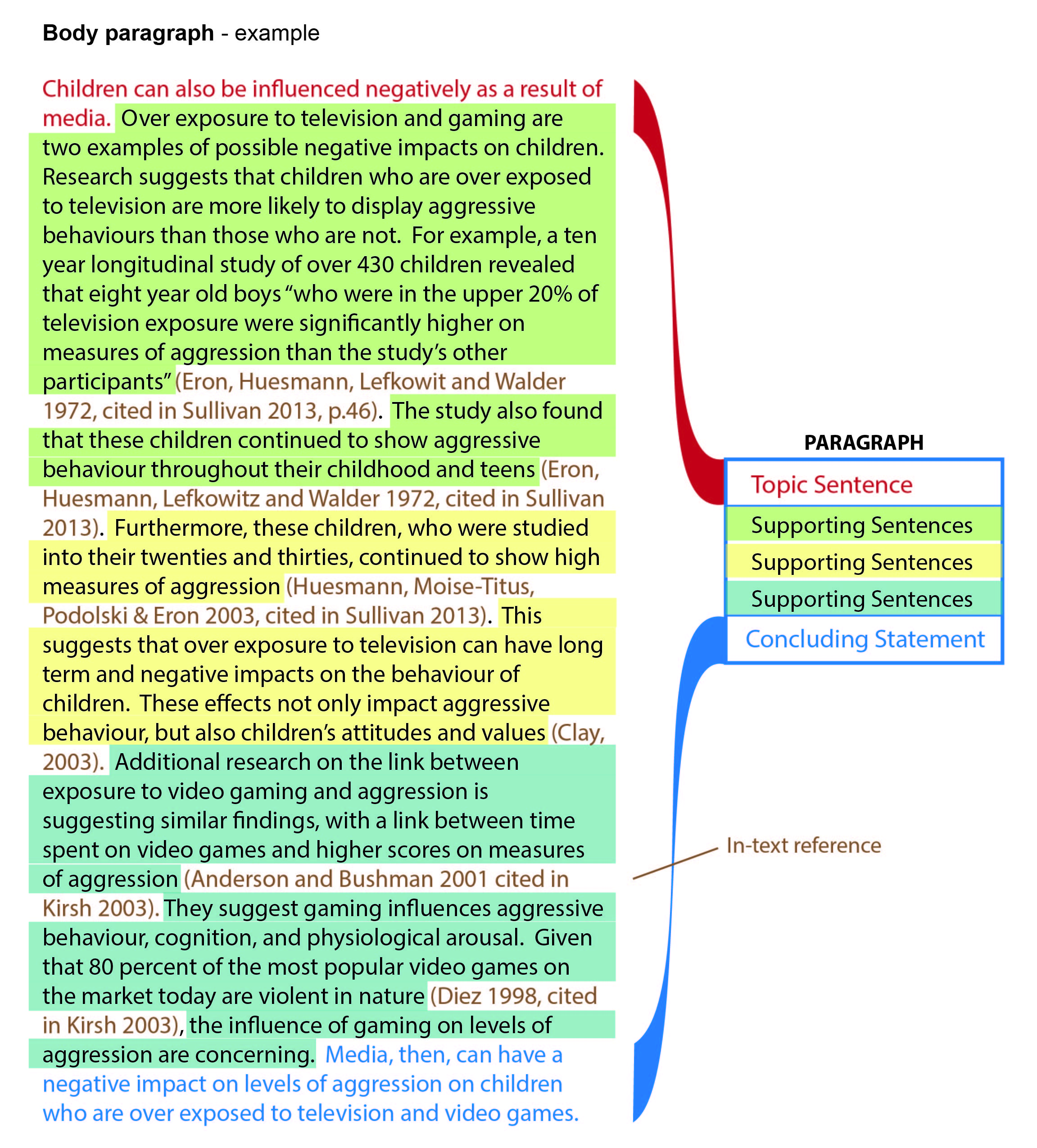

The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next – and largest – is the supporting sentences . These expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay

- Humanities ›

- English Grammar ›

Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

Peter Dazeley / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The body paragraphs are the part of an essay , report , or speech that explains and develops the main idea (or thesis ). They come after the introduction and before the conclusion . The body is usually the longest part of an essay, and each body paragraph may begin with a topic sentence to introduce what the paragraph will be about.

Taken together, they form the support for your thesis, stated in your introduction. They represent the development of your idea, where you present your evidence.

"The following acronym will help you achieve the hourglass structure of a well-developed body paragraph:

- T opic Sentence (a sentence that states the one point the paragraph will make)

- A ssertion statements (statements that present your ideas)

- e X ample(s) (specific passages, factual material, or concrete detail)

- E xplanation (commentary that shows how the examples support your assertion)

- S ignificance (commentary that shows how the paragraph supports the thesis statement).

TAXES gives you a formula for building the supporting paragraphs in a thesis-driven essay." (Kathleen Muller Moore and Susie Lan Cassel, Techniques for College Writing: The Thesis Statement and Beyond . Wadsworth, 2011)

Organization Tips

Aim for coherence to your paragraphs. They should be cohesive around one point. Don't try to do too much and cram all your ideas in one place. Pace your information for your readers, so that they can understand your points individually and follow how they collectively relate to your main thesis or topic.

Watch for overly long paragraphs in your piece. If, after drafting, you realize that you have a paragraph that extends for most of a page, examine each sentence's topic, and see if there is a place where you can make a natural break, where you can group the sentences into two or more paragraphs. Examine your sentences to see if you're repeating yourself, making the same point in two different ways. Do you need both examples or explanations?

Paragraph Caveats

A body paragraph doesn't always have to have a topic sentence. A formal report or paper is more likely to be structured more rigidly than, say, a narrative or creative essay, because you're out to make a point, persuade, show evidence backing up an idea, or report findings.

Next, a body paragraph will differ from a transitional paragraph , which serves as a short bridge between sections. When you just go from paragraph to paragraph within a section, you likely will just need a sentence at the end of one to lead the reader to the next, which will be the next point that you need to make to support the main idea of the paper.

Examples of Body Paragraphs in Student Essays

Completed examples are often useful to see, to give you a place to start analyzing and preparing for your own writing. Check these out:

- How to Catch River Crabs (paragraphs 2 and 3)

- Learning to Hate Mathematics (paragraphs 2-4)

- Rhetorical Analysis of U2's "Sunday Bloody Sunday" (paragraphs 2-13)

- Understanding General-to-Specific Order in Composition

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- Definition and Examples of Transitional Paragraphs

- Padding and Composition

- Definition and Examples of Paragraph Breaks in Prose

- Definition and Examples of Climactic Order in Composition and Speech

- Understanding Organization in Composition and Speech

- Conclusion in Compositions

- Unity in Composition

- Paragraph Length in Compositions and Reports

- A Critical Analysis of George Orwell's 'A Hanging'

- Definition and Examples of Spacing in Composition

- Best Practices for the Most Effective Use of Paragraphs

- 7 Secrets to Success in English 101

- The Parts of a Speech in Classical Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

Purdue Online Writing Lab College of Liberal Arts

Body Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information. Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid - The broadest range of information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim. Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and supports her thesis (a brief wrap-up or warrant).

Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: T ransition, T opic sentence, specific E vidence and analysis, and a B rief wrap-up sentence (also known as a warrant ) –TTEB!

- A T ransition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading. This acts as a hand-off from one idea to the next.

- A T opic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

- Specific E vidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

- A B rief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion. When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument :

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

- Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

- Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

- Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively. This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning (deduction) is organized in three steps:

- Major premise

- Minor premise

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction or syllogistic reasoning:

- Major premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

- Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are great leaders.

- Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear purpose in a crisis.

- Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that (1) all men are mortal (they all die); and (2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as courage , clear purpose , and great ), the connections get tenuous.

For example, some historians might argue that Lincoln didn’t really shine until a few years into the Civil War, after many Union losses to Southern leaders such as Robert E. Lee.

The following is a clear example of deduction gone awry:

- Major premise: All dogs make good pets.

- Minor premise: Doogle is a dog.

- Conclusion: Doogle will make a good pet.

If you don’t agree that all dogs make good pets, then the conclusion that Doogle will make a good pet is invalid.

When a premise in a syllogism is missing, the syllogism becomes an enthymeme. Enthymemes can be very effective in argument, but they can also be unethical and lead to invalid conclusions. Authors often use enthymemes to persuade audiences. The following is an example of an enthymeme:

If you have a plasma TV, you are not poor.

The first part of the enthymeme (If you have a plasma TV) is the stated premise. The second part of the statement (you are not poor) is the conclusion. Therefore, the unstated premise is “Only rich people have plasma TVs.” The enthymeme above leads us to an invalid conclusion (people who own plasma TVs are not poor) because there are plenty of people who own plasma TVs who are poor. Let’s look at this enthymeme in a syllogistic structure:

- Major premise: People who own plasma TVs are rich (unstated above).

- Minor premise: You own a plasma TV.

- Conclusion: You are not poor.

To help you understand how induction and deduction can work together to form a solid argument, you may want to look at the United States Declaration of Independence. The first section of the Declaration contains a series of syllogisms, while the middle section is an inductive list of examples. The final section brings the first and second sections together in a compelling conclusion.

Crafting the Ideal Body of an Essay: Comprehensive Guidelines

What is the body of an essay.

The body of an essay functions as the central core of the paper, situated strategically between the introduction and the conclusion. In this integral section, the author meticulously unveils pivotal arguments and evidence that substantiate the thesis statement, essentially constituting the substantive 'flesh and bones' of the essay. Within this context, every word is judiciously selected, and each sentence is carefully fashioned to educate the reader, dissect the topic through diverse perspectives, and present a persuasive, rigorously argued viewpoint.

Optimal Length of a Body Paragraph

While the length of a body paragraph is not stringently defined, it generally ps from a minimum of three sentences to a maximum of one page. Within the academic realm, the optimal length often hovers around 200 words, or approximately six sentences. This length provides sufficient room for the development of a comprehensive thought but remains concise enough to retain the reader's attention and enable lucid, focused arguments. Each body paragraph ideally begins with a transitional phrase or sentence, linking it cohesively to the preceding content and preserving a harmonious rhythm throughout the college paper.

Fundamental Elements of a Body Paragraph

Every body paragraph can be conceptualized as a self-contained mini-essay, composed of an introduction, body, and conclusion deftly arranged into coherent sentences. Below are the four indispensable components:

- Transition: Serving as the connective tissue between paragraphs, transitions are straightforward yet vital tools that guarantee a seamless and logical flow of ideas. Examples include 'furthermore', 'in contrast', 'moreover', and 'on the other hand'.

- Topic Sentence: Generally inaugurating the paragraph, the topic sentence is a concise declaration that delineates the principal point or claim that the paragraph intends to elucidate. For instance: 'Despite its challenges, online education extends numerous significant advantages.'

- Supporting Arguments: Constituting the core of the paragraph, here the author deploys compelling evidence—facts, statistics, or expert testimony—to reinforce the claim posited in the topic sentence. Employing comparisons can be especially potent in this section, as they enable the reader to grasp the subject matter in relation to another context, thereby enhancing their understanding.

- Summary: Concluding the paragraph, this sentence synthesizes the supporting arguments and reiterates the paragraph’s central point in a refreshed perspective. It should resonate with the reader and adeptly transition them to the subsequent set of ideas. For example, 'Consequently, the flexibility, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness of online education render it an increasingly attractive choice for students globally.'

In the process of crafting the body of an essay, the writer is entrusted with a nuanced balancing act: they are charged with presenting detailed, robust arguments without inundating the reader, and they are expected to interlace complex ideas without sacrificing clarity or coherence. This represents both the art and the formidable challenge of proficient essay writing.

Crafting a Scholarly Body of an Essay: A Step-by-Step Approach

The body of an essay is comparable to the engine of a car—potent yet complex, and essential to the overall operation. Herein, you are tasked to crystallize your arguments, substantiate your claims with solid evidence, and captivate the reader's intellect. In this section, we outline a practical, step-by-step strategy for constructing an essay body that not only resonates with readers but also withstands the discerning scrutiny of any academic evaluator.

Crafting an Outline: The Blueprint of Your Essay

Initiate the process by conceptualizing the skeletal framework of your essay. Analogous to an architect utilizing a blueprint, an outline functions as your navigational aid. Arrange your arguments, contemplate the evidence, and anticipate the effect of each paragraph on the reader. This phase is conducive for experimentation; feel empowered to rearrange the sections as logic and rhythm dictate. Understand that your outline is not rigid but is a dynamic instrument that adapts as your college paper matures.

Penning the First Draft: Breathing Life into Your Outline

This stage represents the point where you infuse vitality into your outline. Transform skeletal points into comprehensive paragraphs, each resonating with precise arguments, vivid examples, and compelling evidence. Visualize your final college paper: consider its appearance, its impact, and its dialogue with the reader. At this juncture, formatting is equally as paramount as content, as it establishes the visual ambiance for your work.

Initiating the First Body Paragraph: Setting the Tone

The opening sentence of your body, reminiscent of a maestro’s initial note in a symphony, orchestrates the tone and tempo for the entire composition. This sentence, often referred to as the 'paragraph leader', must strike a balance between being inviting and authoritative. It is tasked with unfurling the principal argument of the paragraph as conspicuously as a flag heralding the dawn. For example, 'In stark contrast to traditional classrooms, online education offers unparalleled flexibility.'

Crafting the Second Draft: The Crucible of Refinement

This phase represents your crucible, where the magic of refinement occurs. Scrutinize your prose meticulously, excise superfluous elements, and invigorate areas as needed. Grammar must be flawless and style consistently maintained. Reading aloud at this stage proves invaluable; it serves as a litmus test for flow and coherence. Engage in self-questioning: do each of your paragraphs reinforce your thesis in a robust and transparent manner? Are your arguments persuasive and logically sequenced?

Expert Tips for Crafting an Exemplary Draft

- Initiate your essay from any section that resonates with you; starting with the introduction is not a strict requirement.

- Adhere steadfastly to the 'one idea, one paragraph' principle to maintain clarity and focus.

- Be prepared to ruthlessly excise text that does not bolster your argument, and remain receptive to integrating new insights as they emerge.

- Preserve your drafts, even those that fall short of your expectations; they represent the evolution of your thoughts and may prove useful at later stages.

- Systematically compile your sources as you progress, thereby preempting unintentional plagiarism and future complications when crafting your bibliography.

- At this stage, perfectionism is more a foe than a friend; center your efforts on progress rather than perfection.

- Prioritize logical and lucid connections between your ideas, employing transitional phrases to guide the reader seamlessly through your arguments.

Composing the body of an essay is akin to sculpting a delicate artwork; it demands patience, precision, and a profound comprehension of the material at hand. Bear in mind that every writer, irrespective of their level of experience, navigates through this intricate process. With the guidance and exemplars provided by seasoned experts, akin to those at college papers help services, your essay body will not only be substantive and persuasive but will also align with the loftiest academic standards. The capacity to articulate complex ideas in an accessible and captivating manner transcends being a mere skill; it is, indeed, an art form that this guide aspires to help you master.

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

Save time and let our verified experts help you.

- Writing steps

Learning objectives

This resource will help you:

- Understand the purpose and function of academic essay writing.

- Develop your ability to plan and structure an effective academic essay.

- Build skills to develop and produce a credible academic essay.

What is the purpose of essay writing?

Academic essays have multiple purposes, including to:

- analyse, argue, and reflect;

- compare and contrast different positions; and

- discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a position.

Essays can be chronological, sequential, or logical in order. The essay question or purpose should guide how the content is organised and how your position/findings are presented.

- Analysing Assignment Questions (PDF 611 KB) Check out these workshop slides presented by the Student Success team to learn more about analysing assignment questions.

Types of essays

All essays follow a similar structure to that discussed so far, however there are some slight differences to their purpose, tone, vocabulary, and the way evidence is incorporated.

How do you structure an essay?

The table below indicates what is generally included in each section of an essay.

Essay writing (RMIT)

This video (2:08 min) from RMIT provides an excellent overview of the structure of an essay.

Additional resources

- Essay writing (2.17 MB) Check out these workshop slides presented by the Student Success team to learn more about essay writing. This resource contains examples of an Introduction, Body paragraph and a Conclusion.

- Academic Phrasebank (The University of Manchester) Get some ideas for high quality sentence starters from the Academic Phrasebank.

- See an example essay plan and annotated essays from Monash University (2024).

- APA Style (American Pyschological Association, 2024) APA Style is the place to go if you are referencing and formatting in APA7 style.

- What are credible sources? (UniSC) This resource will teach you the skills required to identify credible sources of information.

Access Student Services

- Services and support (UniSC) UniSC offers a range of services for students, including help with academic skills, careers and employability advice, library support, and accessibility and wellbeing services. Visit Services and Support on the Student Portal to find out more.

Your input matters: Shape the future of Academic Skills support!

- Essays | Feedback (UniSC) Help us help you! Share your thoughts on the Essays Guide and shape the resources that will support your academic success. It will take less than 5 minutes to complete this feedback form.

Griffith University. (n.d.). Essay editing and review checklist .

Griffith University. (n.d.). Organise and analyse research literature .

Martin's Journaling Jive!. (2022, July 21). First draft tips for students and writers! . [Video]. YouTube.

McCune, V. (2004). Development of first-year students' conceptions of essay writing. Higher Education, 47 (3), 257-282. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000016419.61481.f9

Microsoft Education. (n.d.). School celebration [GIF]. GIFFY

Morley, J. (2023). Academic phrasebank . The University of Manchester.

Monash University. (2024). Example essay outlines .

RMIT University Library Videos. (2021, October 28). Essay writing . [Video]. YouTube.

The University of Melbourne. (2020, March 26). Task analysis . [Video]. YouTube.

UNSW. (2023, September 19). Construct an essay plan .

- Next: Writing steps >>

- Updated: Dec 17, 2024 2:53 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu.au/skills/essay

- UniSC Library YouTube

Basics of essay writing - Body

The body paragraphs will explain your essay's topic. Each of the main ideas that you listed in your outline will become a paragraph in your essay. If your outline contained three main ideas, you will have three body paragraphs. Start by writing down one of your main ideas, in sentence form.

If your essay topic is a new university in your hometown, one of your main ideas may be "population growth of town" you might say this:

The new university will cause a boom in the population of Fort Myers.

Build on your paragraph by including each of the supporting ideas from your outline In the body of the essay, all the preparation up to this point comes to fruition. The topic you have chosen must now be explained, described, or argued.

Each body paragraph will have the same basic structure.

- Start by writing down one of your main ideas, in sentence form. If your main idea is "reduces freeway congestion," you might say this: Public transportation reduces freeway congestion.

- Next, write down each of your supporting points for that main idea, but leave four or five lines in between each point.

- In the space under each point, write down some elaboration for that point. Elaboration can be further description or explanation or discussion. Supporting Point Commuters appreciate the cost savings of taking public transportation rather than driving. Elaboration Less driving time means less maintenance expense, such as oil changes. Of course, less driving time means savings on gasoline as well. In many cases, these savings amount to more than the cost of riding public transportation.

- If you wish, include a summary sentence for each paragraph. This is not generally needed, however, and such sentences have a tendency to sound stilted, so be cautious about using them.

Each main body paragraph will focus on a single idea, reason, or example that supports your thesis. Each paragraph will have a clear topic sentence (a mini thesis that states the main idea of the paragraph). You should try to use details and specific examples to make your ideas clear and convincing.

Useful links

- 5-paragraph Essay

- Admission Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Classification Essay

- Comparison Essay

- Critical Essay

- Deductive Essay

- Definition Essay

- Exploratory Essay

- Expository Essay

- Informal Essay

- Literature Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Personal Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Research Essay

- Response Essay

- Scholarship Essay

© 2004-2018 EssayInfo.com - Essay writing guides and tips. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Nov 5, 2014 · The body is the longest part of an essay. This is where you lead the reader through your ideas, elaborating arguments and evidence for your thesis. The body is always divided into paragraphs. You can work through the body in three main stages: Create an outline of what you want to say and in what order.

Jun 2, 2022 · A body paragraph is any paragraph in the middle of an essay, paper, or article that comes after the introduction but before the conclusion.Generally, body paragraphs support the work’s thesis and shed new light on the main topic, whether through empirical data, logical deduction, deliberate persuasion, or anecdotal evidence.

If your thesis is a simple one, you might not need a lot of body paragraphs to prove it. If it’s more complicated, you’ll need more body paragraphs. An easy way to remember the parts of a body paragraph is to think of them as the MEAT of your essay: Main Idea. The part of a topic sentence that states the main idea of the body paragraph.

The number of paragraphs in your essay should be determined by the number of steps you need to take to build your argument. To write strong paragraphs, try to focus each paragraph on one main point—and begin a new paragraph when you are moving to a new point or example.

Nov 29, 2023 · The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly. Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence.

Oct 29, 2019 · The body paragraphs are the part of an essay, report, or speech that explains and develops the main idea (or thesis). They come after the introduction and before the conclusion . The body is usually the longest part of an essay, and each body paragraph may begin with a topic sentence to introduce what the paragraph will be about.

When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument: Facts: There is the dead body of Smith.

Aug 16, 2023 · The body of an essay functions as the central core of the paper, situated strategically between the introduction and the conclusion. In this integral section, the author meticulously unveils pivotal arguments and evidence that substantiate the thesis statement, essentially constituting the substantive 'flesh and bones' of the essay.

6 days ago · Contains several body paragraphs, each of which expand on one idea related to your thesis statement or topic. Approximately 75% of the word count, unless stated otherwise. For example, in a 1000-word essay you may have three body paragraphs with around 250 words in each. Each body paragraph contains: Topic sentence with main analysis idea ...

The body paragraphs will explain your essay's topic. Each of the main ideas that you listed in your outline will become a paragraph in your essay. If your outline contained three main ideas, you will have three body paragraphs. Start by writing down one of your main ideas, in sentence form. If your essay topic is a new university in your ...