English Essay: Origin, Development and Growth

Contact form.

English Essay | Origin and Development

Origin and Development of English Essay

Introduction.

The Essay is one of the most remarkable and attractive forms of English Literature . It is a species of prose composition which resembles a short story in size. Both the essay and the short story are written keeping in mind a definite aim and purpose and when it is fulfilled, they are finished. But both are independent and different in form and manner. One chapter of a long philosophical or literary treatise cannot be called an essay, as a chapter of a novel cannot be called a short story.

Essay Definition

No elaborate and complete definition of the essay has been given so far. It is considered as a composition comparatively short, incomplete and unsystematic. Dr. Johnson defined the essay as

“a loose sally of the mind, an irregular, indigested piece, not a regular and orderly composition.”

The Oxford English Dictionary, giving it a more uniform shape, defined it as

“a composition of moderate length on any particular subject, or branch of a subject; originally implying want of finish – (‘an irregular indigested piece’ – Johnson), but now said of a composition more or less elaborate in style, though limited in range.”

These definitions are too vague and narrow to cover essays like Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding . We have essays in verse also such as Essay on Criticism , Essay on Man of Alexander Pope.

Hudson, giving a definition of the essay says:

“The essay, then may be regarded, roughly, as a composition on any topic, the chief negative features of which are comparative brevity and comparative want of exhaustiveness.”

Keeping in mind these two features Crabbe thinks that it is very easy to write essays, because it is essentially superficial in character. But Sainte-Beauve does not agree with this view. He considers it to be the most difficult, as well as delightful form of literary expression because of its brevity and condensation.

The true essay is essentially personal. It is a subjective form of composition like the lyric in poetry . The true essay is a gateway to enter the mind and personality of the writer. The mind of the essayist moves here and there in a rather aimless fashion within the limits of his subject and does not search for depth and profundity.

“A good essay”, says É.V. Lucas, “more than a novel, a poem, a play, or a treatise, is personality translated into print : between the lines must gleam attractive features or we remain cold.”

The essay proper, therefore, is not merely a short analysis of a subject, not a mere epitome, but rather a picture of the writer’s mind as he is affected for the moment by the subject which he is dealing. Montaigne, the first man to write essays so called, was also a personal writer. He said:

“I am the subject of my essays because I myself am the only person whom I know well.”

The essay has a vast scope of subjects. “Apparently there is no subject, from the stars of dust-heap and from the amoeba to man, which may not be dealt within an essay” (Hugh Walker). An essay by Bacon consists of informative knowledge and worldly wisdom; an essay by Addison is thin in thought and diluted, sometimes there is personal gossip and sometimes light didacticism; Lock’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding is formal, ponderous and systematic and full of philosophic principles; the essays of Macaulay are small books. While Bacon deals with philosophical subjects like truth, death and studies, Lamb can write on such small subjects as old and new schoolmasters, chimney sweepers and roast pigs.

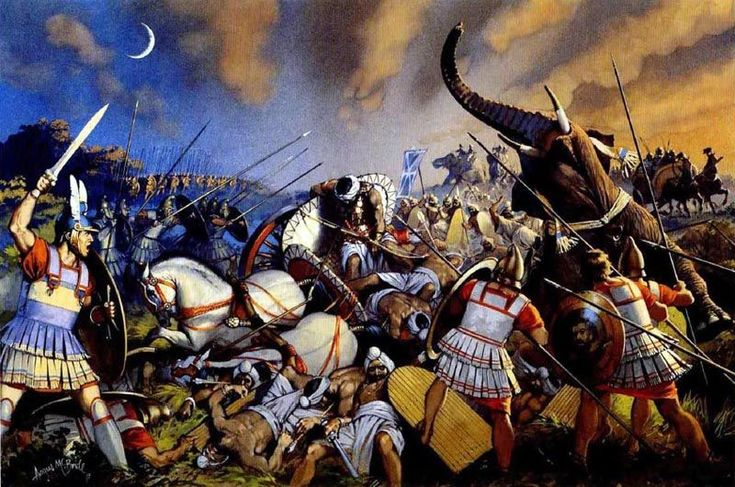

It is generally believed that Montaigne (a Frenchman) was the first writer who wrote what may technically be called essays. But the roots of his writing lie far back in literary history. He owed a great part of his inspiration to the Roman writer Cicero, who in his turn was indebted to Plato. Bacon was the first English writer who transplanted the essay into England, although he followed a different line from Montaigne. The aim of Montaigne was self-revelation, and he was the father of the subjective or the personal essay. Bacon gave it an objective or impersonal turn and made his essay the detached musings of a philosopher.

Essay before Francis Bacon

The foundation of the essay can be traced to ancient Greece and Rome, though it did not flourish there. The French writer, Montaigne, has been given the honour of being the first man to write essays. His prose compositions were written under the name of ‘essais.’ Montaigne’s essays are an attempt to weave out his personal thoughts with an artistic thread. In his essays he describes his personal feelings and experiences Addison aptly remarks: “The most eminent egoist that ever appeared in the world was Montaigne”. His essays are highly subjective and charming.

As Bacon said: “There are certain hollow blasts of wind and secret swellings as seas before a tempest” : in the same way there are certain anticipations of the essay before the formation of its proper form. In fact the Elizabethan age sees the foundation of an English prose style. Before that the earlier specimens have been experimental or totally imitative. Though the age of Elizabeth was essentially poetic and drama became almost an obsession, yet experiments in prose were also carried on. The English tongue was ripe for a prose style. The essay in its beginning developed on three different lines the character-writers of the seventeenth century, the critical prose and the controversial writings.

The character-writers were highly influenced by Theophrastus. These writers depicted with sharpness, humour and satiric touches various types of humanity. Joseph Hall’s Characters of virtues and Vices is written with acuteness in a satirical style. Thomas Overbury survives in literature as the author of A Series of characters based on the ancient Greek book of Theophrastus. It consists of various concise character-sketches as, Milkmaid, Pedant and Franklin etc. John Stephens with his Microcosmography followed this example. Sometimes later Samuel Butler drew the characters of a modern statesman, a mathematician and a romantic writer. Dekker’s Bellman of London introduced several kinds of rogues.

In criticism Caxton’s prefaces may be regarded as early essays in the art. Wilson’s Art of Rhetoric does not come within the limits of essays due to its length and elaboration. Gascoigne’s Note of instruction Concerning the Making of Verse consists of essays.

In the field of polemics Gosson’s School of Abuse which provoked Sidney’s famous Apology for Poetry , is the first document. It is violent and one-sided. Thomas Lodge refuted it in a pamphlet which is not valuable as a critical work. Philip Sidney’s Apology for poetry is “the only critical piece of the sixteenth century which may still be read with pleasure by that vague personage, ‘The general reader.’ (Hugh Walker). Sir George Harrington and George Chapman in their prefaces developed the critical essay. Thomas Nash was a noted controversialist of the period.

Development of the English Essay

Francis bacon.

Bacon’s position in the history of English essay is unique. To him belongs the credit of having written essays first of all in the English language. As Hugh Walker says:

“Although a few of Nash’s tracts may fairly be classed as essays, it is obvious that he did not conceive of himself to be imitating a new fashion of writing. Nor did he in fact do so. Neither did the critics. Still less the forerunners of the character-writers be described as the founders of the essay: they are too unformed and non-literary, Dekker, the successor of Nash and his superior, comes chronologically after Bacon. The latter consequently is the first of the English essayists, as he remains, for sheer mass and weight, of genius, the greatest.”

The general conception of the essay in Bacon was taken from Montaigne whose essays appeared seventeen years before the earliest essays of Bacon. Bacon thought that this form of writing was suitable to his genius and disposition. He speaks of his essays as dispersed meditations’. They are really the outcome of a philosopher’s or thinker’s mind and experience. He took all knowledge for his province. To a man of Bacon’s temperament and accomplishments, with his discursive interests and encyclopedic range, of mind and his thriftiness of time, the essay was a god-send. He wrote his essays in an aphoristic style.

Bacon considered these great essays merely recreation in comparison with his more serious studies. But he was conscious of their popularity. He wrote to Andrews, Bishop of Winchester, in 1622: “I am not ignorant that those kinds of writings would, with less pains and embracements (perhaps), yield more lustre and reputation to my name than those others which I have in hand.” Bacon realised that his essays will “come home to men’s business and bosoms.” On account of their popularity they were translated into French, Latin and Italian languages.

Bacon’s essays are not personal in tone; they are not the confidential chat of a great philosopher. These essays are stately and profound. His essays are not an attempt to communicate a soul like Montaigne’s. Those critics, who acknowledge that the true essay is essentially personal, point out his inferiority in that respect. He lacks true personal touch and the intimate confidence of Charles Lamb – the innocent type. Bacon’s maxims are judicious, condensed and weighty. He seems to be looking down with absolute dispassionateness from the pulpit, and determining what course of conduct pays best. John Freeman points out that Bacon is not an intimate but reserved figure, not a talker but a writer, not a babbler but a rhetorician, not a companion but a teacher, not a friend but a great chancellor, not a familiar friend forgetting his dignity but a supple states man asserting it; preferring to suppress, equivocate, and dissemble, and to justify every obliquity- anything rather than candidly pour himself out and leave the justification to the reader.”

There were a few writers, however, in the age of Bacon who continued the personal vein in their essays introduced by Montaigne, and the foremost among them was Ben Jonson, whose forceful personality continually breaks through his Discoveries . Like Montaigne, Ben Jonson’s self-dominates in his writings which imparts a peculiar charm to his essays. Jonson’s style combines lucidity, crispness and force in a degree rivalling Bacon’s.

Abraham Cowley

Cowley cultivated a form of the essay more intimate and confidential, though less profound, weighty and philosophical, than the Baconian. The charm of his essays is largely due to their simple and sincere revelation of self. They are the friendly chat of a thoughtful and reflective spectator of life. Nothing that Cowley has written is more delightful than what he has written directly about himself. Edmund Gosse has described Cowley as the pure essayist, as contra-distinguished from the heavy, condensed and incoherent didacticism of Bacon:

“Cowley, who first understood what Montaigne was bent upon introducing, is a pure essayist, and leads on directly to Steele and Addison, and to Charles Lamb. If we read Cowley’s chapter On Myself , we find contained in it, as in a nutshell, the complete model and style of what an essay should be, – elegant, fresh, confidential, constructed with as much care as a sonnet”.

Essay in The Restoration Age (1660-1700)

John dryden.

Dryden introduced a new variety, called the Critical Essay. Among the earliest of Dryden’s essays was the Essay of Dramatic Poesy (1668), which is still the best known, and contains the most elaborate exposition of his critical principles, though it is surpassed in interest by the admirable Preface to the Fables . These critical essays entitled Dryden to the honour of being not only the father of English criticism” but also “the first master of a prose which is adapted to the everyday needs of expression, and yet has dignity enough to raise to any point of the topmost peaks of eloquence.” Dryden’s style is remarkably free from mannerisms of any kind and its characteristics are lucidity and easy grace. He gave up the long-winded, cumbrous sentences of the earlier prose writers. He used a simple, straightforward, vigorous mode of expressing his meaning,

There were two other writers in the Restoration Age- Sir William Temple and Lord Halifax , who were at once politicians and men of letters and contributed greatly to the development of the English essay. Sir William Temple, a statesman and a diplomat is at his best in the essays Of Gardening and Of Health and Long Life . “In a sense,” says Legouis “Temple is the first classicist; and his clear-cut style, unencumbered, simple, smooth but still compact, symmetrical and yet free from monotony, has almost always the rhythm and finish of the modern prose.” Lamb praises “the plain, natural chit-chat of Temple.” In Macaulay’s opinion “his style is stately and splendid. Temple is confidential and good natured.” Lord Halifax is chiefly known for his famous essay, The Character of a Trimmer . It is written in a masterly style and full of political wisdom.

Essay in the Eighteenth Century

The periodical essay.

The early years of the eighteenth century saw the rise of journalism and the essay began to appear in the periodicals Daniel Defoe’s paper, the Review , first published in 1704, established the periodical essay. “The journalistic essay,” remarks T. G. Williams, “is loose-knit, easy-paced and discursive. Addressed to citizens of the world, it attempts a synthesis of experience, and allows of digression into whatever bypaths seem to answer the writer’s mood.”

The real vogue of the periodical essay, however, began with the publication of The Tatler (1709) and The Spectator (1711). With these two periodicals are inextricably associated the names of Richard Steele and Joseph Addison , acknowledged masters of the periodical essay. Steele started The Tatler with the declared object of exposing “the false arts of life, of pulling off the disguises of cunning, vanity and affectation, and of recommending a general simplicity in dress, discourse and behaviour.” It stopped publication after two years, and was replaced by The Spectator in March, 1711. Over 550 issues of the Spectator appeared before it ceased publication in December, 1712. In this enterprise Steele was associated with Addison. Addison’s aim was to “enliven morality with wit and to temper wit with morality.” He was the master of pleasant humour, delicate irony and satire. His style is the model of the middle style-never loose, or obscure or unmusical.

Steele and Addison were ideally matched as literary partners; each was the exact complement of the other. Steele was rash, erratic and original; Addison prudent, reflective and painstaking. Steele was more inventive than Addison and Addison was more effective than Steele. In some ways Steele was greater than Addison; he was more modest, more warmhearted and more human. As a literary figure, however, though one of the earliest, wisest, and wittiest of English essayists, Steele ranks quite distinctly below Addison.

Among other contributors to the periodicals in the age of Queen Anne may be mentioned Pope (1688-1774) and Swift (1667-1745). Pope’s prose writings are often excellent and he possessed many of the qualities of a periodical essayist . Swift was, however, by nature and temperament unfitted for the work of an essayist. He was a misanthrope and did not possess that breadth of vision which is the essential characteristic of a good essayist. His humour was too grim and sardonic and his intellect too massive for the essay.

Henry Fielding , Dr. Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith followed Addison and Steele’s way. Fielding contributed his essays to The Champion and The Covent Garden Journal . The introductory chapters to the books of his great novel Tom Jones are fine pieces of prose. The earliest works of Dr. Johnson appeared in The Gentleman’s Magazine . He himself launched the Rambler and the Idler. His style is bombastic, antithetical and is marked with Latinism. But now-a-days his essays would be read rather as a duty than for pleasure, because he lectures us, whereas with Steele and Addison we feel that we are on equal terms with two friendly men of the world.

Oliver Goldsmith is one of the greatest essayists of the eighteenth century. Many of his essays in The Bee and The Citizen of the World are remarkable for their extraordinary power, boldness and originality. They are written in a style whose wonderful charm has never failed to impress the reader. There is in them an imitable vein of humour which constitutes one of the secrets of his charm.

Essay in the Nineteenth Century

After Goldsmith the periodical essay of the literary type was in decline. In the beginning of the nineteenth century the periodical newspaper gave place to the critical journal, commonly called the Review , It had little concern with social and personal topics; its main purpose was political. In them ample space was devoted to the literary criticism. The most important of these reviews were The Gentlemen’s Magazine , The Edinburgh Review , The Quarterly Review , Blackwood’s Magazine and The London Magazine . They are of special importance in the history of the essay, because, while they have been used for many other purposes, they have been pre-eminently the medium of the essay.

Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (1775-1834) endeared himself to generations of Englishmen by his Essays of Elia (1832) and Last Essays of Elia (1833). Lamb belongs to the intimate and self-revealing essayists, of whom Montaigne is the original, and Cowley the first exponent in England. He has been rightly called ‘the Prince of English Essayists’ because there are essayists like Bacon of more massive greatness, and others like Sir Thomas Browne, who have attained the heights of rhythmic eloquence, but there is no other essayist who has in an equal degree the power to charm. Lamb takes the reader into his confidence and conceals nothing from him. His essays are a living testimony to his sweetness of disposition and gentleness of heart. In his essays humour and pathos are inseparable from each other, they are different facts of his predecessors; they are conversational, lack both restraint and formality and are frequently rhetorical. They are yet nonetheless delightful. They are amusing, paradoxical, ingenious, touching, poetic and eloquent. His “whimwhams”, as he called them, found their best expression in quaint words and antique phrases and sometimes far-fetched, yet never forced comparisons in which he abounds.

Few notable essays of Charles Lamb are- Dream Children: A Reverie , The Superannuated Man etc.

William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt (1778-1830) is one of the best essayists of the nineteenth century. His essays are divisible into two classes- essays on literary criticism and essays on miscellaneous subjects. In both spheres he stands very high. His critical essays, although sometimes marred by his extra-literary prejudices, entitle him to be placed in the foremost rank of English critics. His miscellaneous essays are autobiographical, they frankly tell about his temperament, his enthusiasm and his limitations. His style has no blemishes, and is particularly free form mannerisms of all kinds. Like Addison and Dr. Johnson his language is always dignified. Though his place in the history and growth of the English essay is undoubtedly lower than Lamb’s; yet it is certainly higher than of the rest with the possible exception of R. L. Stevenson. His important Essay includes On a Sun-Dial .

Thomas De Quincey

Like Lamb and Hazlitt, Thomas De Quincey (1785-1859) was frankly personal and his best essays are autobiographical. He wrote, however, on a great number of subjects and often so discursively that he never far reached the subjects which he proposed. Though his intellect was acute and subtle, he is at his best when he leaves the world of fact and leads us into his dreams and visions. His greatest contribution to the English essay is his sonorous prose. He brought to his task a magical control of long-drawn and musical cadences.

Leigh Hunt (1784-1859) turned to the essayists of the age of Queen Anne for his model; for the qualities he displays are much the same as theirs. But unlike them, he is confidential in tone. It is this intimacy which gives charm to his essays like Coaches and their Horses , Deaths of Little Children , A Visit in the Zoological Garden and Month of May . But Hunt lacked one thing which was requisite to make him a great essayist – mass and weight of thought. Moreover, his style is not a great style, although it is an easy and agreeable one. Like his contemporaries, he has also written critical essays on Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth and Coleridge.

The Essay in the Victorian Age

The Victorian age saw the birth of a new genre, the historical essay . Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-59) may be looked upon as the founder of this type. Among his essays the best are those which he wrote on English history. He also wrote some biographical essays for the Encyclopedia Britannica. He brought to the composition of his essays a mind that was richly stored with detail, and perfectly clear in its conviction. This allowed him to set forth his theme with a simplicity that avoided every compromise, and this firm outline, once defined, he decorated with every embellishment of allusion and picturesque detail. He has his faults also. He had strong perusal and political prejudices and this often marred the quality of his work. He is often grandiloquent and rhetorical. We also do not find in him the intimacy of personal confidence which is the distinguishing feature of the essays of Elia. As a critic has pointed out: “In the hands of Macaulay the essay ceases to be a confession or an autobiography: it is strictly impersonal; it is literary, historical, or controversial; vigorous, trenchant, and full of party prejudice.” He is merely the essayist-historian. But he was a competent and distinguished reviewer and raised the standard of reviewing considerably.

Thomas Carlyle

In marked contrast with Macaulay is Thomas Carlyle, the prophet and the censor of the Victorian era. He was a man of extreme honesty and sincerity, and his essays exposed and denounced many of the vices of his age. He was deeply influenced by German philosophy. His essays are critical, biographical, historical, social and political. His style is remarkable for its strength and tempestuous force. He can sometimes command a beauty of expression that deeply touches the heart, and can attain a piercing melody, wistful and moving that is almost lyrical

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold tended to mould all his prose material into the form of essays. He is one of the best critics in English literature. He is a critic of literature and a critic of society. As a critic he advocated a high moral purpose for all forms of art, and insisted rather too dogmatically, on very balanced and clear-cut expression. His own style in prose, however, lacks precision, and is marred occasionally by unseemly repetitions. But his vocabulary is always select and often he attains to a felicity of phrase not easily surpassed.

Among other essayists of the Victorian age, mention may be made of Henry Newman (1801-90), John Ruskin (1819-1900) and Walter Pater (1839-94). Newman was the master of a supple prose and at times, of a highly wrought style. Ruskin’s style is rich, ornate and full of gorgeous imagery. Pater wrote in a prose of rare beauty. His Appreciations remains his best work and is the best exponent of his aesthetic theories. But these writers write in a very ponderous and heavy style which is marked by elaboration and finish. They also lack the personal touch and conversational tone of Lamb. Hence their work is nearer to the treatise than to the essay. It is for this reason that critics like Orlo Williams deny them the title of the essayists.

R. L. Stevenson

R. L. Stevenson recaptured the charm of the personal type of essay. He was a born essayist. As Hugh Walker says: “Nature made him an essayist, and he cooperated with nature, developing, and strengthening the gifts with which he was endowed at birth”. He has often been compared with Lamb for his sweetness of temper and his personal charm, constantly exercised by taking the reader into his confidence. He is always moral without being didactic. He could write a beautiful essay on almost any topic. He set out to cultivate a clear and forcible style. He studied English sounds systematically and diligently, and used them with harmony.

The Essay in the Twentieth Century

The twentieth century proved to be a fertile ground for the development of the Essay. It yielded a rich and varied harvest. The innumerable daily papers and weekly and monthly periodicals, provide an unlimited scope for the essayist. In the modern age both personal and objective essays have been written by various authors.

G. K. Chesterton

G K Chesterton deserves a high reputation as an essayist and critic of literature and society. Among his volumes of essays are Tremendous Trifles , A Shilling for My Thoughts , All Things Considered etc. His style is remarkable for its ingenuity, a curious sort of humour and its paradoxes and epigrams.

E. V. Lucas

E.V. Lucas is also a writer of the personal essay. He revived the tradition of Lamb, and is also his editor and biographer “ Less wistful and touching than Lamb” , Lucas has something of his master’s gusto and enthusiasm, even though the objects that inspire his feelings are necessarily different”. Lucas has a much wider experience of life than Lamb. He has an inexhaustible store of new subjects because he has an observant, sympathetic eye that makes all life its peculiar province Lucas is a regular contributor to the Punch: his humour is as quick and graceful as his perfect style. Like Lamb, Lucas is also attracted by the picturesqueness and gorgeousness of the city life of London. His major essay includes The Town week .

A. G. Gardiner

A. G. Gardiner is perhaps the most delightful of the modern essayists. He wrote under the pen name of ‘Alpha of the Plough’. His famous essays are collected in the volumes Pebbles on the Shore , Leaves in the Wind and Many Furrows . He has a rare understanding of men and affairs and wields a fluent and persuasive style enlivened by the touches of quiet humour. His essays are full of amusing anecdotes and homely illustrations drawn from everyday experience and they read like short stories.

Robert Lynd

In his style and outlook Robert Lynd cultivates the manner of R. L. Stevenson. His essays display his Stevensonian humour, reflectiveness and sympathy. Like E.V. Lucas, he builds his essays out of mere trifles and makes them the occasion of trenchant criticism of life. He has the confidential manner of the personal essayist. His style is simple and less elaborate, and therefore devoid of the mannerisms of R.L. Stevenson.

Hilaire Belloc

Hilaire Belloc occupies a very high place among the modern essayists by virtue of the volumes of his essays like On Nothing , On Something and On Everything . He has a clear incisive style in which humour, never really removed from satire, plays an important part.

Other Essayists

There are many other essayists of the twentieth century who follow the tradition of the personal essay. A few of them are – Max Beerbohm, Alice Meynell, Maurice Baring, Philip Guedella, George Bernard Shaw (Freedom) and Aldous Huxley.

Thus we see that the Essay, unknown by name up to the sixteenth century in England, has been developed brilliantly and on various lines by the writers of the succeeding generations. Let us hope and look for a brighter future for this genre of literary composition.

Hello, Viewers! Besides being the Founder and Owner of this website, I am a Government Officer. As a hardcore literary lover, I am pursuing my dream by writing notes and articles related to Literature. Drop me a line anytime, whether it’s about any queries or demands or just to share your well-being. I’d love to hear from you. Thanks for stopping by!

Related posts:

- Sir Roger at Church | Summary, Analysis, Explanation

- Of Truth by Francis Bacon | Summary, Analysis, Explanations

- Of Study by Francis Bacon | A Short and Simple Analysis

- A Passage to England by Nirad C. Chaudhuri Summary and Analysis

- Of Study by Francis Bacon | Summary and Line By Line Analysis

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- You don't have any recent items yet.

- You don't have any courses yet.

- Add Courses

- You don't have any books yet.

- You don't have any Studylists yet.

Final Origin and Development of english Essay

- Multiple Choice

Course : English (First Language) (ELS6)

University : palamuru university.

Students also viewed

- B.COM MPCS DBMS LAB External QP

- On Selecting Effective Patterns for Fast Support Vector Regression Training

- Orange HRM Test Plan

- importent question in cprorgraing in palamuru university

- python sec paper in palamuru university

- object oriented programming language in palamuru university

Related documents

- A Study on Customer Satisfaction Towards Sonalika Tractors, Hoshiarpur

- Richard 20R20Goldberg 20Solutions 20Manual

- B.LAW(sem-2) unit-3 - Notes

- Algebra IMP Theorems - Notes

- 6th semester physics electronics notes

Growth and Development of the Essay

The Beginning-The Sixteenth Century: Today the essay is a recognized literary genre. But it took a long time to attain its present glory and status. As Mr. Rhystruly says, “it is unnecessary to go profoundly into the history and origin of the essay—whether it derives from Socrates or Siranney the Persian-since, like all living things, its present is more important than its past”. (Virginia Woolf). Yet it is customary to trace out its origin and beginning. It is generally accepted that the form of essay originated from the dialogues of Socrates. But while discussing the history of the English essay, the origin of the essay is traced to Montaigne, the sixteenth century French writer. The English essay was in existence before Bacon published his Essays in 1597. The writing of character-sketches after the manner of Theophrastus was a part of education in the middle ages. John Awdeley’s Fraternity of Vagabonds has essays on the ‘Company of Cozeners and Shifters’ and Harman’s Caveat, published in 1566, has essays on different kinds or classes of vagabonds. Critical essays too had begun to emerge before Bacon, Caxton’s prefaces, Gascoigne’s Notes, and the writings of Campion, Daniel and Gosson have but slight value. Gosson’s School of Abuse (1579) is memorable, for it provoked the best essay that Sidney ever wrote, Sidney’s Apology was begun in 1580 and published in 1595. There is the fervour of the author behind this essay. The style is uncertain. There are too many parentheses and relative clauses. The proper prose style has not yet been formed.

The next great name is that of Thomas Nash (1567-1601) who, according to Isaac Walton, “put a greater stop to those malicious ‘Mar prelate’ pamphlets than a much wiser man had been able to “The Anatomy of Absurdity (1589) is a parade of his learning. Pierce Penniless (1592) is a vigorous attack on the contemporary follies. Nash did not have a sense of when to stop. But as Dekker remarked: “Ingenious and ingenuous, fluent, factious, T. Nash, from whose abundant pen honey flowed to thy friends, and mortal aconite to the enemies”. Nash had a heavy and coarse wit.

Lord Bacon: However, it was Lord Bacon who transplanted the essay into England. It is with the publication of Bacon’s essays in 1597, and 1625, that the regular essay in English begins. Bacon felt that he was originating a new fashion in writing and thus approached the essay in the modern sense.

Bacon rightly calls his essays ‘dispersed meditations’. Speaking of his early essays Hugh Walker says, “In the early essays, the sentences are nearly all short, crisp and sententious. There are few connectives. Each sentence stands by itself, the concentrated expression of weighty thought”.

However, Bacon’s essays are “loose thoughts, thrown out without much regularity, because “Bacon was thrifty of his thoughts and his literary material”. But they have a continuity, and the author reveals a graceful ease and a confidence in his powers. Bacon does not whisper to the reader in a friendly tone; he is always lordly and stately. He speaks of masque, triumphs and gardens, and he is fond of splendour. The subject of his essays is not very substantial. Most of his essays are concerned with the day-to-day problems of ordinary life. Bacon was a moralist and a politician so his essays deal with these themes also. Bacon remains, however, “the first of English essayists”.

The Seventeenth Century: Bacon was the father of the English essay. But the essay, as we know it today, is different from anything that he ever wrote. His prose style had a great influence, but his essays did not win any disciples or imitators. In the 17 th century the essay developed in the hands of Sir William Temple, Cowley and Dryden, who made it more flexible, companionable and pleasant. The authoritative tone of Bacon’s heavy moralising is replaced by an essay of intimate contact with the reader and it is on these lines that the essay was to develop in the future. The writing of Character Sketches’ by Hall. Overbury and Earle during this century also promoted the growth of the essay.

Bacon’s example was followed by William Cornwallis, whose Essays appeared in 1600, and by Robert Johnson, who gave Essays in 1601. Cornwallis used the essay “as a painter’s boy on a board”.

Next to these is Ben Johnson’s Timber or Discoveries, a collection of 171 jottings which are connected with one another. Johnson’s style combines lucidity, terseness and strength in a degree rivalling even Bacon’s. It is capable of rising to eloquence, but a plain subject is treated in a plain and simple way.

With Sir Thomas Browne the English essay acquires a new dimension. Browne writes condensed prose. His artistry is unmatched in English save Lamb’s. There is neither systematic philosophy nor science in his works, but real literature. He is, in reality, the greatest essayist in English. His style is remarkable for scholasticism and Latinism.” Nicholas Breton carries on the tradition of Bacon to whom he dedicated

His Characters upon Essays, Moral and Divine (1615). A better writer was Geoffrey Mynshul, whose Essays and Characters of a Prison and Prisoners is based upon personal experience and, therefore, has a depth of feeling.

The Eighteenth Century: The Revolution of 1688 gave rise to greater freedom of the individual and fostered the growth of the two leading political parties. The religious controversy of the bygone ages came to an end. The time was ripe for the emergence of periodicals, journals and newspapers. Defoe did some significant work for the essay by writing The Instability of Human Greatness. But Steele made history with the publication of the first number of The Tattler on April 12, 1709.

The Tattler appeared thrice a week and it was all written by Steele at the beginning; but it was closed down on January 2, 1711. On March 1, 1711 appeared in The Spectator, a joint venture of Addison and Steele though Addison was a contributor to the earlier paper too. But Steele independently planned The Tattler and also sketched the character of Sir Roger. As such we can presume that he gave the idea of the Spectator Club. The figure of the Spectator was drawn by Addison. The Spectator Club had members representing various classes of society. This was an improvement over the crude machinery of The Tattler and it anticipated the Pickwick Club and also the social or domestic novel of the century. The Club provided a unity to this group of essays.

Addison is “a far more finished writer, more correct, more scholarly, more subtly humorous”. The style of Steele is “full of faults and careless blunders; and redeemed, like that, by his sweet and compassionate nature”. Steele is valuable for his reference for the domestic pieties and for his love of women and children. At his best he is superior to Addison in the tone of his writing, not in his style. Steele is autobiographical and gives us a form of the personal essay. He expresses his heart without any reserve. Addison has a greater charm of conversation and his essays reveal more of his head. This makes him typical of his age.

Another important paper emerged in March, 1713. It was The Guardian. Pope contributed eight essays to The Guardian. These and his prefaces show that he had the true makings of a periodical essayist. One essay pleads for humanity to animals, another is against human flattery in dedications, and two deal with the Short Club where he laughs at himself.

The most significant essayist In the second half of the 18 th century is Dr. Johnson. His Rambler (1750-52) is the first of the classical periodicals after The Guardian. Then he also contributed to The Adventure and to his own The Idler. His early essays have a heavy style and a serious subject- matter, and thus have the typical Johnsons’ style with their antitheses and Latinisms.

In Oliver Goldsmith (1728-74), another essayist of the eighteenth century, we again find ease and charm. Goldsmith is indeed one of the greatest essayists in English literature. Many of his essays in The Bee and Citizen of the World are remarkable for their extraordinary power, boldness and originality. They are written in a style whose wonderful charm has never failed to impress the reader. There is in them an inimitable vein of humour which constitutes one of the secrets of their charm. His style is as careful as Addison’s and much simpler than Johnson’s.

The periodical essay declined after Goldsmith, More and more of political writing began to fill the pages of the periodicals even though literary men like Smollett were the contributors. The Mirror (1779-80) introduced Henry Mackenzie, the author of The Man of Feeling and a few other minor essayists. Richard Cumberland’s The Observer also shows a conscious reaction against the style of Dr. Johnson.

The Early Nineteenth Century: The nineteenth century witnessed the real flowering of the essay. The century seemed to have opened the flood- gates for the essay as a recognised form of literature. Both the personal and the impersonal kinds of essays began to flourish in this period. It was in this age that a number of literary and critical magazines and reviews came into being and most of the budding writers launched upon their careers by contributing articles of them. The Edinburgh Review and the Quarterly Review generally published essays of a critical and weighty character. The Blackwood Magazine, The Fraser’s Magazine and The London Magazine popularised the essay, both critical and personal.

Charles Lamb carries on the tradition of Steele and Goldsmith, the tradition of self-portraiture. Like Montaigne he himself is the subject of his essays. Lamb is constantly autobiographical, his whole life may be constructed from the ‘Essays of Elia’. ‘The Essays of Elia’ are beautiful pieces revealing Lamb’s personality, his sweetness of heart, his tenderness of disposition, his wisdom and sympathy. Lamb takes the reader into his confidence and conceals nothing from him. His essays have the great charm of spontaneity and naturalness and really lyrics in prose.

Further on, Hunt was the first literary critic to do justice to Shelley and Keats. His work is full of self-contradictions-blame and praise of Wordsworth and Coleridge. Possibly he attacked these and Scott because they were Tories. He was a sentimentalist who overdid Whigs. His intellect was capable of making the beautiful appear empty or hateful. He admired in others what he felt he had achieved in his own work. This is something of the classical or neoclassical spirit. His criticism is admirable where it is not coloured by prejudice. As Hugh Walker says, “He was singularly sensitive, and so when he trusted feeling he was almost invariably right. This is the secret of the charm of his critical work”. He succeeds in communicating his own enjoyment. It is this that Lamb and Shelley loved in him.

Hazlitt was a greater essayist than most of his contemporaries. His essays can be divided into two classes-essays on literary criticism and essays on miscellaneous subjects, the latter often being of an intimate and personal nature. In both spheres he stands very high. His critical essays are contained in many volumes-Characters of Shakespeare’s Play, Lectures on English Poets, English Comic Writers, Dramatic Literature of the Age of Elizabeth, and The Spirit of the Age. These critical essays, although sometimes marred by his extra-literary prejudices entitle him to be placed in the foremost ranks of English critics.

Also Read :

- Compare Hamlet with Macbeth, Othello and other Tragedies

- “The Pardoner’s Tale” is the finest tale of Chaucer

- Prologue to Canterbury Tales – (Short Ques & Ans)

- Confessional Poetry – Definition & meaning

De Quincey, the famous opium-eater, wrote his essays in a highly poetic ornate and musical style which reminds us of Thomas Browne. His Confessions of an Opium Eater has something of the intimacy and confidence of Lamb.

The Victorian Age: Throughout this age the essay continued to develop in two directions-the critical and the personal. Among the critical literary essayists of the middle and later nineteenth century, the most illustrious names are those of Macaulay, Carlyle, Ruskin, Pater and Matthew Arnold. Macaulay is a brilliant, thoughtful, unbalanced critic with a pictorial, grandiloquent style.

Thomas Carlyle stands as a contrast to Macaulay. Carlyle (1795-1882) is the prophet and censor of the Victorian era. He is the richest and the profoundest of all historical essayists. But his essays have been overshadowed by his greater works. They touch upon all the great departments of his literary activity. They are critical, biographical, historical, social and political. All his characteristic dogmas and beliefs will be found expressed in one or the other of his essays. Carlyle’s style is remarkable for its strength and tempestuous force. Carlyle can sometimes command a beauty of expression that deeply touches the heart, and can attain a piercing melody, wistful and moving, that is almost lyrical.

Matthew Arnold (1822-88) tended to mould all his prose material into the form of essays. Even his letters in Friendship’s Garland are essays. But the best is Essays in Criticism. His essays make him the most influential of English writers. His Culture and Anarchy is also called an ‘Essay in Social and Political Criticism’. As a critic Arnold advocates a high moral purpose for all forms of art and recommends a very well-balanced and clear-cut expression. His own style lacks precision and is marred occasionally by unseemly repetition. But his vocabulary is selected and the felicity of phrases remarkable.

Among the other essayists of the Victorian age, mention may be made of Henry Newman (1801-90), John Ruskin (1819-1900) and Walter Pater (1839-94). Newman was the master of a supple prose, and at times of a highly wrought style. Ruskin’s style is rich, ornate, and full of gorgeous imagery. Pater wrote in a prose of rare beauty. He used the essay for the expression of exquisite artistic sensation. His appreciation is his best work.

The Twentieth Century: The essay developed more in the 20 th century than it has developed in any other era. The innumerable daily papers, weeklies, monthlies and other periodicals and journals provided immense scope for the essayist. The modern essay is so varied and miscellaneous that it is difficult to categorize it. The most important modern essayists are Chesterton, Lucas, Gardiner, Lynd and Belloc.

G.K. Chesterton (1868-1938) started his career as an essayist very early in life. His essays are the best examples, in style and outlook, of the Personal Essay. He has an inexhaustible store of new subjects because he has an observant, sympathetic eye that makes all life its peculiar province. E. B. Lucas was a regular contributor to Punch. His humour is as quiet and graceful as his style. There is nothing obtrusive, hard, or forensic about Lucas’s writing. His essays belong generally to the tender, graceful tradition of Charles Lamb.

A.C. Ward calls him The Modern Lamb’.

Chesterton’s friend Hillarie Belloc also is a born essayist. He occupies a high place among the modern essayists by virtue of the volumes of his essays like On Nothing’. ‘On something’ and ‘On Everything. He has a clear, incisive style in which humour, never really removed from satire, plays an important part.

A. G. Gardiner (1885-1946) is, perhaps, the most delightful of the modern essayists. He wrote under the pen-name of ‘Alpha of the Plough. There at the head of the Plough, flames the great star that points to the pole. I will hitch my little wagon to that sublime image. I will be Alpha of the Plough. He has personality and humour, a background of literature, depth and thoughtfulness, and he has polished his art to perfection. He has a rare understanding of men and affairs and wields a fluent and persuasive style enlivened by touches of quiet humour. His essays are full of amusing anecdotes and homely illustrations drawn for everyday experience.

Robert Lynd (1879-1949) is also a gifted essayist and critic. He follows in style the manner of R.L. Stevenson. His famous work is A Peal of Bells. He can very well display Stevensonian humour, reflectiveness and sympathy.. Like Lucas he builds his essays out of mere trifles and makes them an occasion of a trenchant criticism of life. His style is simple and less elaborate and devoid of the mannerisms of Stevenson. He tries to please as well as instruct.

PLEASE HELP ME TO REACH 1000 SUBSCRIBER ON MY COOKING YT CHANNEL (CLICK HERE)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel

🔥 Don't Miss Out! Subscribe to Our YouTube Channel for Exclusive English Literature, Research Papers, Best Notes for UG, PG & UGC-NET!

🌟 Click Now! 👉

Recent Posts

Mantra full story in English by Munshi Premchand

“Grih Daah” story by Munshi Premchand

Summary of “Kafan” by Munshi Premchand

The Rise of Novel Apartments: A Fresh Perspective on Modern Living

A Comparative Analysis of Medieval and Renaissance English Literature

Describe The Happy Ending Of Play Antony and Cleopatra

The Politics of Antony and Cleopatra By Shakespeare

Some Explanation from Indian English Prose

Summary Of No Man’s An Island By John Donne

Ideas Contained In The Essay The Secret of Work by Swami Vivekanand

The Great Age of the English Essay

From the pens of spectators, ramblers, idlers, tattlers, hypochondriacs, connoisseurs, and loungers, a new literary genre emerged in eighteenth-century England: the periodical essay. Situated between classical rhetoric and the novel, the English essay challenged the borders between fiction and nonfiction prose and helped forge the tastes and values of an emerging middle class.

This authoritative anthology is the first to gather in one volume the consummate periodical essays of the period. Included are theSpectator cofounders Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, literary lion Samuel Johnson, and Romantic recluse Thomas De Quincey, addressing a wide variety of topics from the oddities of virtuosos to the private lives of parrots and the fantastic horrors of opium dreams.

In a lively and informative introduction, Denise Gigante situates the essayists in the context of the contemporary Republic of Letters and highlights the stylistic innovations and conventions that distinguish the periodical essay as a literary form. Critical notes on the essays, a chronology, descriptions and a map of key London sites, and a glossary of eighteenth-century English terms complete the anthology—a uniquely pleasurable survey of the golden era of British essays.

About the Author

Denise Gigante

Denise Gigante teaches British Romantic literature, and poetry over a longer tradition. Her interests include poetic form and aesthetics, bibliomania and literary antiquarianism, gastronomy, the history and form of the essay, material print culture, and the mixed-media work of William Blake.

She is currently completing work on The Cambridge History of the British Essay, a monumental history the development of the essay genre by a global network of authors that includes her own chapter, “On Books: The Bibliographical Essay” She is also working to complete The Mental Traveller: William Blake, a study of Blake’s illuminated poetry in relation late Medieval and Renaissance Christian iconography and the literary tradition of Pilgrimage, in a heavily illustrated volume to be published as part of the Clarendon Lecture Series by Oxford University Press.

Her most recently published book is Book Madness: A Story of Book Collectors in America (Yale University Press, 2023), a narrative experiment in literary history that explores different pockets of book collecting in mid-nineteenth-century America. The story is based on the sale of Charles Lamb’s antiquarian books—a quintessential book lover’s library—in New York in 1848.

She is also the author of The Keats Brothers: The Life of John and George, (Harvard UP, 2011), Life: Organic Form and Romanticism (Yale UP, 2009), Taste: A Literary History (Yale UP, 2005), and two anthologies: The Great Age of the English Essay (Yale UP, 2008) and Gusto: Essential Writings in Nineteenth-Century Gastronomy (Routledge, 2005) as well as numerous articles and book chapters on topics of interest from taste and gastronomy to book collecting and poetic form

Development & Tradition of the Essay

In this section, the historical development of the essay will be discussed.

The essay, a term first coined in the sixteenth century, is a brief prose composition that presents ideas and opinions about a single topic. The word essay comes from the French word essai, which means “an attempt.”

The following table describes different types of essays.

In 1580, French philosopher Michel de Montaigne originated the essay genre when he published his multivolume work titled Essays. Montaigne wrote familiar essays on topics such as death, friendship, virtue, education, politics, friendship, and human nature. The importance of Essays rests with Montaigne’s originality; he focused on human nature rather than academic learning and theories.

In 1597, Francis Bacon, an English philosopher and statesman, published Essays and Counsels, a collection of brief formal essays . The publication was so popular that larger editions were issued in 1612 and 1625. Bacon was the first English writer to use the essay genre developed by Montaigne, but Bacon shaped the literary form to suit his own style. While Montaigne’s essays are personal, Bacon’s essays are logical, brief, and practical.

Eighteenth-century readers enjoyed periodical essays in publications such as the Tatler and the Spectator, which were England’s first major literary magazines. These journals included formal essays, but it was the satiric humor of the periodical essays that proved especially popular with the masses.

Colonial Americans read persuasive essays such as Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which helped spark the American Revolution.

Romantic writers of the nineteenth century found the essay genre appealing because they expressed personal feelings. Prominent essayists of this time included William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb. Known and respected for offering a subjective opinion in his essays, Hazlitt wrote about economics, politics, painting, the theater, and literature.

During the 1820s, Hazlitt’s close friend Charles Lamb wrote familiar essays , which he submitted to the newly created London Magazine. Master of the familiar essay, Lamb entertained his readers and established himself as a great nineteenth-century essayist.

American Ralph Waldo Emerson’s formal essay Nature, written in 1836, presents the principle ideas of transcendentalism. Within the next ten years, Emerson published two collections of essays, including the well-known Self-Reliance, an essay instructing readers to trust their own judgment above that of all others.

Noted novelists and short story writers such as Ralph Ellison, George Orwell, James Thurber, Aldous Huxley, and E. B. White all contributed essays during the twentieth century.

Which type of essay addresses a subject with a serious tone?

- Informal essay

- Periodical essay

- Personal essay

- Formal essay

Reveal Answer

The answer is D. Formal essays, like the ones written by Francis Bacon, are logical, structured, and serious.

Back to Top

The Evolution of the English Language: A Detailed Journey Through Time

The English language, as we know it today, is a rich tapestry woven from centuries of cultural exchange, invasions, and internal transformations. From its humble origins in the 5th century to its global dominance in the 21st century, English has evolved dramatically, adapting to various social, political, and technological changes. Let’s explore this fascinating journey in detail, tracing the evolution of the English language across four major periods: Old English, Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English.

1. Old English (5th to 11th Centuries)

English first began to take shape with the migration of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes to Britain in the 5th century. These tribes, originally from regions in what is now Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, brought with them West Germanic dialects that eventually merged to form what we call Old English. The language of this era was far removed from modern English and would be largely incomprehensible to contemporary speakers.

Phonology: Old English had a complex system of vowels and consonants, many of which no longer exist in modern English. Pronunciation was vastly different, marked by a variety of sounds that disappeared over time or were modified through later linguistic shifts.

Grammar: Old English was highly inflected, meaning that the endings of words changed depending on their role in a sentence. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns were modified to indicate case (such as nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive), number (singular or plural), and tense. This gave the language a grammatical flexibility that modern English lacks.

Vocabulary: The lexicon of Old English was predominantly Germanic, sharing similarities with languages like Old High German and Old Norse. Although it did borrow a few words from Latin (due to the influence of Christianity) and from Celtic languages spoken by the original inhabitants of Britain, it remained largely insulated from external linguistic influences until the Norman Conquest.

2. Middle English (11th to 15th Centuries)

The Norman Conquest of 1066 marked a turning point in the development of the English language. William the Conqueror and his Norman French-speaking elite imposed their language on the English court, clergy, and legal system. As a result, Middle English evolved, marked by significant changes in both vocabulary and grammar.

French Influence: The Normans introduced a flood of French vocabulary into English, especially in the realms of law, government, art, and fashion. Words like "court," "jury," "govern," and "parliament" entered English during this time. While Old English survived as the language of the common people, the French influence reshaped the lexicon and added new layers of complexity to the language.

Simplified Grammar: During the Middle English period, the inflectional system of Old English began to break down. Word order became more important for indicating meaning, as grammatical markers like case endings diminished in importance. This simplification allowed English to become more accessible and flexible, though it also necessitated the use of auxiliary verbs (such as "do," "have," and "will") to express tense and mood.

Phonological Shifts: One of the most significant linguistic changes during this period was the Great Vowel Shift, a radical transformation in the pronunciation of long vowels. This shift, which took place over several centuries, altered the way English vowels were pronounced, gradually aligning them more closely with modern English sounds. For example, the word "bite" was once pronounced more like "beet," and "meet" was pronounced as "mate." This shift helped set the stage for modern English pronunciation.

3. Early Modern English (15th to 17th-18th Centuries)

The invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century revolutionized English, accelerating its standardization and dissemination. Early Modern English emerged during this period, marked by a newfound consistency in spelling, grammar, and usage.

Standardization: With the advent of printing, English became more uniform. Printers like William Caxton played a key role in standardizing English spelling, which had been highly variable up to this point. Books, pamphlets, and other printed materials began to reach wider audiences, and the language started to stabilize as a result. Spelling conventions that were set during this period have endured, even as pronunciation has continued to change.

Latin and Greek Revival: The Renaissance, with its renewed interest in classical knowledge, brought a wave of Latin and Greek loanwords into English. Scholars, scientists, and philosophers began incorporating classical terms into their writings, enriching the language with new vocabulary for abstract concepts, technical terms, and scholarly discourse. Words like "agenda," "virus," "manual," and "algebra" were borrowed from these classical languages during this period.

Phonetic Changes: The phonetic evolution of English continued, particularly as the Great Vowel Shift progressed. The changes in vowel pronunciation created a language that was phonetically distinct from its Middle English predecessor, even as its written form remained largely the same. This created the notorious inconsistency between English spelling and pronunciation that learners of the language struggle with to this day.

4. Modern English (17th-18th Century Onward)

Modern English began to take its present form around the 17th century. The colonial expansion of the British Empire and the rise of global trade spread the language across continents, leading to the development of distinct regional dialects and varieties.

Global Expansion: As English-speaking settlers and traders established colonies in North America, Africa, Asia, and Australia, English became a global language. This expansion led to the development of new English dialects, such as American English, Canadian English, and Indian English. Each of these dialects incorporated local words and linguistic features, further enriching the global lexicon of English.

Linguistic Borrowing: English continued to borrow words from a variety of languages as it interacted with different cultures around the world. For example, "kangaroo" comes from an Aboriginal Australian language, "safari" from Swahili, and "curry" from Tamil. This constant borrowing and adaptation is one of the reasons English has such an extensive vocabulary today, estimated at over a million words.

Technological Influence: The 20th and 21st centuries have brought even more changes to English, driven by technological advancements. The rise of the internet, social media, and global communication has introduced new slang, abbreviations, and forms of expression. Words like "selfie," "emoji," and "hashtag" are products of the digital age, illustrating how quickly language can adapt to new cultural phenomena.

The evolution of the English language is a testament to its resilience and adaptability. From its Germanic roots in the 5th century to its global dominance in the modern era, English has been shaped by historical events, cultural exchanges, and technological innovations. Each period in its development contributed new elements to its structure and vocabulary, creating a language that is both complex and versatile.

Today, English continues to evolve, influenced by global communication and emerging technologies. Its history is a reflection of the diverse cultures and societies that have contributed to its growth, and its future promises even more exciting changes as it remains a living, dynamic language.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The essays of Montaigne were short in compass, light in tone and treatment, personal and discursive. They appeared in France about 1580 and in English in 1603. Dr. Samuel Johnson has defined the essay "as a loose sally of the mind, an irregular undigested piece; not a regular or orderly composition." The definition, though not complete, is ...

Dec 3, 2021 · Origin and Development of English Essay Introduction. The Essay is one of the most remarkable and attractive forms of English Literature. It is a species of prose composition which resembles a short story in size. Both the essay and the short story are written keeping in mind a definite aim and purpose and when it is fulfilled, they are finished.

There were two other writers in the Restoration Age- Sir William Temple and Lord Halifax, who were at once politicians and men of letters and contributed greatly to the development of the English essay. Sir William Temple, a statesman and a diplomat is. December, 1712. In this enterprise Steele was associated with Addison.

May 9, 2023 · The English essay was in existence before Bacon published his Essays in 1597. The writing of character-sketches after the manner of Theophrastus was a part of education in the middle ages. John Awdeley’s Fraternity of Vagabonds has essays on the ‘Company of Cozeners and Shifters’ and Harman’s Caveat, published in 1566, has essays on ...

From the pens of spectators, ramblers, idlers, tattlers, hypochondriacs, connoisseurs, and loungers, a new literary genre emerged in eighteenth-century England: the periodical essay. Situated between classical rhetoric and the novel, the English essay challenged the borders between fiction and nonfiction prose and helped forge the tastes and values of an emerging middle class.

In 1597, Francis Bacon, an English philosopher and statesman, published Essays and Counsels, a collection of brief formal essays. The publication was so popular that larger editions were issued in 1612 and 1625. Bacon was the first English writer to use the essay genre developed by Montaigne, but Bacon shaped the literary form to suit his own ...

essays. T.S. Eliot has written such essays in the modern times. Swift, Pope, Johnson, Goldsmith, Stevenson and Newman are his notable predecessors. The Birth of the Essay-The earliest essay-anonymous and trivial-Remedies against Discontentment appeared in 1556. But we owe to Bacon and 1557 both the birth of English Essay. Bacon published ten

The Emergence and Development of English An Introduction This textbook provides a step-by-step introduction to the history of the English language (HEL), offering a fresh perspective on the process of language change. Aimed at undergraduate students, The Emergence and Development of English is accessibly written,

the English Essay (). Her essays on the essay include On Coffee Houses, Smoking and the English Essay Tradition (); Pedantry and Party Politics: Essays in the Public Sphere (); and Sometimes a Stick is Just a Stick: The Essay as (Organic) Form (). J C is a writer and independent scholar based in Berlin and Dijon.

Oct 17, 2024 · The Norman Conquest of 1066 marked a turning point in the development of the English language. William the Conqueror and his Norman French-speaking elite imposed their language on the English court, clergy, and legal system. As a result, Middle English evolved, marked by significant changes in both vocabulary and grammar.