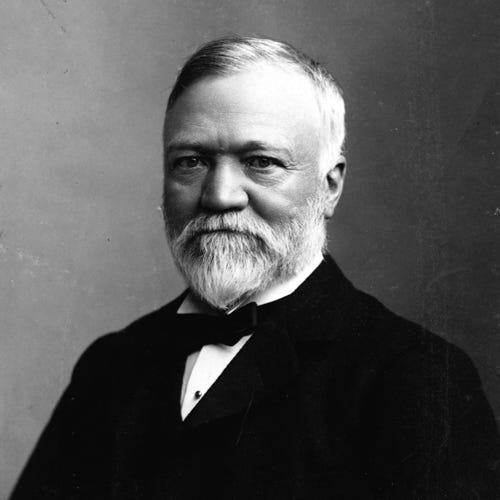

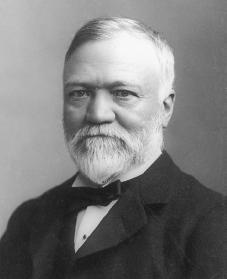

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a self-made steel tycoon and one of the wealthiest businessmen of the 19th century. He later dedicated his life to philanthropic endeavors.

(1835-1919)

Who Was Andrew Carnegie?

After moving to the United States from Scotland, Andrew Carnegie worked a series of railroad jobs. By 1889, he owned Carnegie Steel Corporation, the largest of its kind in the world. In 1901 he sold his business and dedicated his time to expanding his philanthropic work, including the establishment of Carnegie-Mellon University in 1904.

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Although he had little formal education, Carnegie grew up in a family that believed in the importance of books and learning. The son of a handloom weaver, Carnegie grew up to become one of the wealthiest businessmen in America.

At the age of 13, in 1848, Carnegie came to the United States with his family. They settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, and Carnegie went to work in a factory, earning $1.20 a week. The next year he found a job as a telegraph messenger. Hoping to advance his career, he moved up to a telegraph operator position in 1851. He then took a job at the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1853. He worked as the assistant and telegrapher to Thomas Scott, one of the railroad's top officials. Through this experience, he learned about the railroad industry and about business in general. Three years later, Carnegie was promoted to superintendent.

Steel Tycoon

While working for the railroad, Carnegie began making investments. He made many wise choices and found that his investments, especially those in oil, brought in substantial returns. He left the railroad in 1865 to focus on his other business interests, including the Keystone Bridge Company.

By the next decade, most of Carnegie's time was dedicated to the steel industry. His business, which became known as the Carnegie Steel Company, revolutionized steel production in the United States. Carnegie built plants around the country, using technology and methods that made manufacturing steel easier, faster and more productive. For every step of the process, he owned exactly what he needed: the raw materials, ships and railroads for transporting the goods, and even coal fields to fuel the steel furnaces.

This start-to-finish strategy helped Carnegie become the dominant force in the industry and an exceedingly wealthy man. It also made him known as one of America's "builders," as his business helped to fuel the economy and shape the nation into what it is today. By 1889, Carnegie Steel Corporation was the largest of its kind in the world.

Some felt that the company's success came at the expense of its workers. The most notable case of this came in 1892. When the company tried to lower wages at a Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, the employees objected. They refused to work, starting what has been called the Homestead Strike of 1892. The conflict between the workers and local managers turned violent after the managers called in guards to break up the union. While Carnegie was away at the time of strike, many still held him accountable for his managers' actions.

Philanthropy

In 1901, Carnegie made a dramatic change in his life. He sold his business to the United States Steel Corporation, started by legendary financier J.P. Morgan. The sale earned him more than $200 million. At the age of 65, Carnegie decided to spend the rest of his days helping others. While he had begun his philanthropic work years earlier by building libraries and making donations, Carnegie expanded his efforts in the early 20th century.

Carnegie, an avid reader for much of his life, donated approximately $5 million to the New York Public Library so that the library could open several branches in 1901. Devoted to learning, he established the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, which is now known as Carnegie-Mellon University in 1904. The next year, he created the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching in 1905. With his strong interest to peace, he formed the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1910. He made numerous other donations, and it is said that more than 2,800 libraries were opened with his support.

Besides his business and charitable interests, Carnegie enjoyed traveling and meeting and entertaining leading figures in many fields. He was friends with Matthew Arnold, Mark Twain, William Gladstone, and Theodore Roosevelt. Carnegie also wrote several books and numerous articles. His 1889 article "Wealth" outlined his view that those with great wealth must be socially responsible and use their assets to help others. This was later published as the 1900 book The Gospel of Wealth .

Carnegie died on August 11, 1919, in Lenox, Massachusetts, at the age of 83.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Andrew Carnegie

- Birth Year: 1835

- Birth date: November 25, 1835

- Birth City: Dunfermline, Scotland

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Andrew Carnegie was a self-made steel tycoon and one of the wealthiest businessmen of the 19th century. He later dedicated his life to philanthropic endeavors.

- Business and Industry

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Death Year: 1919

- Death date: August 11, 1919

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Lenox

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Andrew Carnegie Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/business-leaders/andrew-carnegie

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 26, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- People who are unable to motivate themselves must be content with mediocrity, no matter how impressive their other talents.

- The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.

- I cannot tell you how proud I was when I received my first week's own earnings. One dollar and twenty cents made by myself and given to me because I had been of some use in the world!

- I always liked the idea of being my own master, of manufacturing something and giving employment to many men.

- In bestowing charity, the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves.

- I should as soon leave to my son a curse as the almighty dollar.

- No party is so foolish as to nominate for the presidency a rich man, much less a millionaire. Democracy elects poor men.

- There is always room at the top in every pursuit. Concentrate all your thought and energy upon the performance of your duties. Put all your eggs into one basket and then watch that basket.

- Do not make riches, but usefulness, your first aim.

- I congratulate poor young men upon being born to that ancient and honorable degree which renders it necessary that they should devote themselves to hard work.

- The aim of the millionaire should be, first, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display and extravagances.

Philanthropists

Aaron Judge

Dolly Parton

Michael J. Fox

Alec Baldwin

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Tyler Childers

Prince William

Michelle Obama

Oprah Winfrey

Madam C.J. Walker

Prince Harry

Jimmy Carter

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Andrew Carnegie

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 9, 2021 | Original: November 9, 2009

Scottish-born Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was an American industrialist who amassed a fortune in the steel industry then became a major philanthropist. Carnegie worked in a Pittsburgh cotton factory as a boy before rising to the position of division superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1859.

While working for the railroad, he invested in various ventures, including iron and oil companies, and made his first fortune by the time he was in his early 30s. In the early 1870s, he entered the steel business, and over the next two decades became a dominant force in the industry. In 1901, he sold the Carnegie Steel Company to banker John Pierpont Morgan for $480 million. Carnegie then devoted himself to philanthropy, eventually giving away more than $350 million.

Andrew Carnegie: Early Life and Career

Andrew Carnegie, whose life became a rags-to-riches story, was born into modest circumstances on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, the second of two sons of Will, a handloom weaver, and Margaret, who did sewing work for local shoemakers. In 1848, the Carnegie family (who pronounced their name “carNEgie”) moved to America in search of better economic opportunities and settled in Allegheny City (now part of Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania . Andrew Carnegie, whose formal education ended when he left Scotland, where he had no more than a few years’ schooling, soon found employment as a bobbin boy at a cotton factory, earning $1.20 a week.

Did you know? During the U.S. Civil War, Andrew Carnegie was drafted for the Army; however, rather than serve, he paid another man $850 to report for duty in his place, a common practice at the time.

Ambitious and hard-working, he went on to hold a series of jobs, including messenger in a telegraph office and secretary and telegraph operator for the superintendent of the Pittsburgh division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1859, Carnegie succeeded his boss as railroad division superintendent. While in this position, he made profitable investments in a variety of businesses, including coal, iron and oil companies and a manufacturer of railroad sleeping cars.

After leaving his post with the railroad in 1865, Carnegie continued his ascent in the business world. With the U.S. railroad industry then entering a period of rapid growth, he expanded his railroad-related investments and founded such ventures as an iron bridge building company (Keystone Bridge Company) and a telegraph firm, often using his connections to win insider contracts. By the time he was in his early 30s, Carnegie had become a very wealthy man.

Andrew Carnegie: Steel Magnate

In the early 1870s, Carnegie co-founded his first steel company, near Pittsburgh. Over the next few decades, he created a steel empire, maximizing profits and minimizing inefficiencies through ownership of factories, raw materials and transportation infrastructure involved in steel making. In 1892, his primary holdings were consolidated to form Carnegie Steel Company.

The steel magnate considered himself a champion of the working man; however, his reputation was marred by the violent Homestead Strike in 1892 at his Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mill. After union workers protested wage cuts, Carnegie Steel general manager Henry Clay Frick (1848-1919), who was determined to break the union, locked the workers out of the plant.

Andrew Carnegie was on vacation in Scotland during the strike, but put his support in Frick, who called in some 300 Pinkerton armed guards to protect the plant. A bloody battle broke out between the striking workers and the Pinkertons, leaving at least 10 men dead. The state militia then was brought in to take control of the town, union leaders were arrested and Frick hired replacement workers for the plant. After five months, the strike ended with the union’s defeat. Additionally, the labor movement at Pittsburgh-area steel mills was crippled for the next four decades.

In 1901, banker John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) purchased Carnegie Steel for some $480 million, making Andrew Carnegie one of the world’s richest men. That same year, Morgan merged Carnegie Steel with a group of other steel businesses to form U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation.

READ MORE: Andrew Carnegie Claimed to Support Unions, But Then Destroyed Them in His Steel Empire

Andrew Carnegie: Philanthropist

After Carnegie sold his steel company, the diminutive titan, who stood 5’3”, retired from business and devoted himself full-time to philanthropy. In 1889, he had penned an essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” in which he stated that the rich have “a moral obligation to distribute [their money] in ways that promote the welfare and happiness of the common man.” Carnegie also said, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

Carnegie eventually gave away some $350 million (the equivalent of billions in today’s dollars), which represented the bulk of his wealth. Among his philanthropic activities, he funded the establishment of more than 2,500 public libraries around the globe, donated more than 7,600 organs to churches worldwide and endowed organizations (many still in existence today) dedicated to research in science, education, world peace and other causes.

Among his gifts was the $1.1 million required for the land and construction costs of Carnegie Hall, the legendary New York City concert venue that opened in 1891. The Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Mellon University and the Carnegie Foundation were all founded thanks to his financial gifts. A lover of books, he was the largest individual investor in public libraries in American history.

Andrew Carnegie: Family and Final Years

Carnegie’s mother, who was a major influence in his life, lived with him until her death in 1886. The following year, the 51-year-old industrial baron married Louise Whitfield (1857-1946), who was two decades his junior and the daughter of a New York City merchant. The couple had one child, Margaret (1897-1990). The Carnegies lived in a Manhattan mansion and spent summers in Scotland, where they owned Skibo Castle, set on some 28,000 acres.

Carnegie died at age 83 on August 11, 1919, at Shadowbrook, his estate in Lenox, Massachusetts . He was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in North Tarrytown, New York.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

American Experience

Biography: andrew carnegie.

- Share on Facebook

- Share On Twitter

- Copy Link Dismiss https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/carnegie-biography/ Copy Link

At a time when America struggled -- often violently -- to sort out the competing claims of democracy and individual gain, Carnegie championed both. He saw himself as a hero of working people, yet he crushed their unions. One of the most successful entrepreneurs of his age, he railed against privilege. A generous philanthropist, he slashed the wages of the workers who made him rich.

One of the captains of industry of 19th century America, Andrew Carnegie helped build the formidable American steel industry, a process that turned a poor young man into the richest man in the world.

From Scotland to America

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835. An ancient town that had taken pride in being Scotland's medieval capital, Dunfermline had fallen on hard times. Andrew's father was a weaver, a profession the young Carnegie was expected to follow. But by the 1840s, the royal castle lay in ruins, as did the town's once-booming linen industry, which had long enjoyed a reputation for producing the finest damask linens in Great Britain. The industrial revolution had destroyed the weavers' craft. When the steam-powered looms came to Dunfermline in 1847, hundreds of hand loom weavers became expendable. Andrew's mother went to work to support the family, opening a small grocery shop and mending shoes.

Dunfermline weavers struggling to feed their families put their faith in a political panacea called Chartism, a popular movement of the British working class. The Chartists believed that by allowing the masses to vote and to run for Parliament, they could seize government from the landed gentry and make conditions better for the working man. Carnegie's father Will and his uncle Tom Morrison led the Chartist movement in Dunfermline. In 1842, Tom organized a national general strike. Will, meanwhile, published letters in various radical magazines and was president of one of the local weavers' societies. Despite the enthusiasm of the Dunfermline Chartists, Chartism fizzled out in 1848, after Parliament rejected the Chartists' demands for the final time.

"I began to learn what poverty meant," Andrew would later write. "It was burnt into my heart then that my father had to beg for work. And then and there came the resolve that I would cure that when I got to be a man."

Andrew's mother, Margaret, fearing for the survival of her family, pushed the family to leave the poverty of Scotland for the possibilities in America, about which she had heard encouraging reports. "This country's far better for the working man than the old one," assured Margaret's sister, who had lived in America for the last eight years.

The Carnegies auctioned all their belongings only to find that they still didn't have enough money to take the entire family on the voyage. They managed to borrow 20 pounds and find found room on a small sailing ship, the Wiscasset. At the harbor in Glasgow, they and the rest of the human cargo were assigned to tightly squeezed bunks in the hold. It would be a 50-day trip, with no privacy and miserable food.

The Carnegies, like many emigrants that year, discovered their ship's crew undermanned; they and the others were frequently asked to pitch in. Many were not much help; half the passengers lay sick in their bunks, the roll of the sea too much. It was grueling, but there was always hope. The passengers traded stories about the lives they would find in the New World.

Finally, New York City came into sight. The ships sailed past the plush farmland and forests of the Bronx, dropping anchor off Castle Garden at the lower end of Manhattan. It was still seven years before New York would build an immigration station there and nearly half a century before Ellis Island would open. The Carnegies disembarked, disoriented by the activity of the city but anxious to continue on to the final destination -- Pittsburgh.

The Carnegies booked passage on a steamer up the Hudson River to Albany, where they found a number of jostling agents eagerly competing to carry them west on the Erie Canal. At 35 miles per day, it was slow travel and not particularly pleasant. Their "quarters" were a narrow shelf in a hot, unventilated cabin. Finally, they reached Buffalo. From there, it was only three more trips by canal boat. After three weeks travel from New York, they finally arrived in Pittsburgh, the place where Andrew would build his fortune.

Welcome to Pittsburgh When the Carnegies arrived in 1848, Pittsburgh was already a bustling industrial city. But the city had begun to pay an environmental price for its success. The downtown had been gutted by fire in 1845; already the newly constructed buildings were so blackened by soot that they were indistinguishable from older ones.

The Carnegies lived in a neighborhood alternately called Barefoot Square and Slab town. Their home on Rebecca Street was a flimsy, dark frame house -- a far cry from their cozy stone cottage in Scotland. "Any accurate description of Pittsburgh at that time would be set down as a piece of the grossest exaggeration," Carnegie wrote, setting aside his usually optimistic tone. "The smoke permeated and penetrated everything.... If you washed your face and hands they were as dirty as ever in an hour. The soot gathered in the hair and irritated the skin, and for a time ... life was more or less miserable."

Often described as "hell with the lid off," Pittsburgh by the turn of the century was recognized as the center of the new industrial world. A British economist described its conditions: "Grime and squalor unspeakable, unlimited hours of work, ferocious contests between labor and capital, the fiercest commercial scrambling for money literally sweated out of the people, the utter absorption by high and low of every faculty in getting and grabbing, total indifference to all other ideals and aspirations."

But if Pittsburgh had become a focus of unrestrained capitalism, it also drove the American economy. And to the men who ran them, the city's industries meant not just dirty air and water, but progress. Pittsburgh's furnaces symbolized a world roaring toward the future, spurred onward by American ingenuity and omnipotent technology.

William Carnegie secured work in a cotton factory. Andrew took work in the same building as a bobbin boy for $1.20 a week, and he later worked as a messenger boy in the city's telegraph office. He did each job to the best of his ability and seized every opportunity to take on new responsibilities. He memorized Pittsburgh's street layout as well as the names and addresses of the important people he delivered to.

Carnegie often was asked to deliver messages to the theater. He arranged to make these deliveries at night--and stayed on to watch plays by Shakespeare and other great playwrights. In what would be a life-long pursuit of knowledge, Carnegie also took advantage of a small library that a local benefactor made available to working boys.

One of the men Carnegie met at the telegraph office was Thomas A. Scott, then beginning his impressive career at Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott was taken by the young worker and referred to him as "my boy Andy," hiring him in 1853 as his private secretary and personal telegrapher at $35 a month.

"I couldn't imagine," Carnegie said many years later, "what I could ever do with so much money." Ever eager to take on new responsibilities, Carnegie worked his way up the ladder at Pennsylvania Railroad and succeeded Scott as superintendent of the Pittsburgh Division. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Scott was hired to supervise military transportation for the North, and Carnegie worked as his right hand man.

The Civil War fueled the iron industry, and by the time the war was over, Carnegie saw the potential in the field and resigned from Pennsylvania Railroad. It was one of many bold moves that would typify Carnegie's life in industry and earn him his fortune. He then turned his attention to founding the Keystone Bridge Company in 1865, where he focused on replacing wooden bridges with stronger iron ones. In three years, he had an annual income of $50,000.

By 1868 Carnegie, then 33, was worth $400,000 (nearly $5 million today). But his wealth troubled him, as did the ghosts of his radical past. He expressed his uneasiness with the businessman's life, promising that he would stop working in two years and pursue a life of good works: "To continue much longer overwhelmed by business cares and with most of my thoughts wholly upon the way to make more money in the shortest time, must degrade me beyond hope of permanent recovery. I will resign business at thirty-five, but during the ensuing two years I wish to spend the afternoons in receiving instruction and in reading systematically."

Making Money and Starting a Family Carnegie would continue making unparalleled amounts of money for the next 30 years. Two years after he wrote that letter Carnegie would embrace a new steel refining process being used by Englishman Henry Bessemer to convert huge batches of iron into steel, which was much more flexible than brittle iron. Carnegie threw his own money into the process and even borrowed heavily to build a new steel plant near Pittsburgh in 1875. Carnegie was ruthless in keeping down costs and managed by the motto "watch costs, and the profits take care of themselves."

"I think Carnegie's genius was first of all, an ability to foresee how things were going to change," says historian John Ingram. "Once he saw that something was of potential benefit to him, he was willing to invest enormously in it."

In 1880, Carnegie, at age 45, began courting Louise Whitfield, age 23. Carnegie's mother was the primary obstacle to the relationship. Nearly 70 years old, Margaret Carnegie had long been accustomed to her son's complete attention. He adored her. They shared a suite at New York's Windsor Hotel, and she often accompanied him -- even to business meetings. Some have hinted that she exacted a promise from Carnegie that he remain a bachelor during her lifetime.

Louise was the daughter of a well-to-do New York merchant and a semi-invalid mother. Like Carnegie, Louise was devoted to her mother, who required constant medical attention. Unlike Margaret Carnegie, however, Mrs. Whitfield encouraged her daughter to spend time with her suitor. Carnegie's mother meanwhile did her best to undermine the relationship

Undaunted, the couple were engaged in September 1883, but they kept it a secret for the sake of mother Margaret. In 1886, Margaret's health was failing. In July, Carnegie wrote to Louise from his summer home in Cresson, PA. "I have not written to you because it seems you and I have duties which must keep us apart," he wrote. "Everything does hang upon our mothers, with both of us -- our duty is the same, to stick to them to the last. I feel this every day."

On November 10, 1886, Margaret Carnegie died. Even then, Carnegie was reluctant to make the engagement public, out of respect for his mother. "It would not seem in good taste to announce it so soon," Carnegie wrote Louise. They were finally married on April 22, 1887, at the Whitfield home. The wedding was very small, very quiet, very private. There was no maid of honor, no best man, no ushers, and only 30 guests.

By this point, Carnegie had entered into a business partnership with Henry Clay Frick, an industrialist in coal-based fuel. Carnegie was unusual among the industrial captains of his day because he preached for the rights of laborers to unionize and to protect their jobs. However, Carnegie's actions did not always match his rhetoric. Carnegie's steel workers were often pushed to long hours and low wages. In the Homestead Strike of 1892, Carnegie threw his support behind Frick, the plant manager, who locked out workers and hired Pinkerton thugs to intimidate strikers. Many were killed in the conflict, and it was an episode that would forever hurt Carnegie's reputation and haunt him as a man.

Still, Carnegie's steel juggernaut was unstoppable, and by 1900 Carnegie Steel produced more steel than all of Great Britain. That was also the year that financier J.P. Morgan mounted a major challenge to Carnegie's empire. While Carnegie believed he could beat Morgan in a battle lasting five, 10 or 15 years, the fight did not appeal to the 64-year old man eager to spend more time with his wife Louise and daughter Margaret.

Carnegie wrote the asking price for his steel business on a piece of paper and had one of his managers deliver the offer to Morgan in 1901. Morgan accepted without hesitation, buying the company for $480 million. Carnegie personally earned $250 million (approximately $4.5 billion today). "Congratulations, Mr. Carnegie," Morgan said to Carnegie when they finalized the deal, "you are now the richest man in the world.

Philanthropy Fond of saying that "the man who dies rich dies disgraced," Carnegie turned his attention to giving away his fortune. He abhorred charity, and instead put his money to use helping others help themselves. He spent much of his collected fortune on establishing over 2,500 public libraries as well as supporting institutions of higher learning.

Carnegie also was one of the first to call for a "league of nations" and he built a "a palace of peace" that would later evolve into the World Court. His hopes for a civilized world of peace were destroyed, though, with the onset of World War I in 1914. Louise said that with these hostilities her husband's "heart was broken."

Carnegie lived for another five years, but the last entry in his autobiography was the day World War I began. By the time of Carnegie's death in 1919, he had given away $350 million ($4.4 billion in 2010 dollars). Through philanthropy and the pursuit of world peace, Carnegie hoped perhaps that donating his wealth to charitable causes would mitigate the grimy details of its accumulation, and in the public memory, he may have been correct. Today, he is most remembered for his generous gifts of music halls and educational grants, and libraries.

Now Streaming

American Coup: Wilmington 1898

The little-known story of a deadly 1898 race massacre and coup d’état in Wilmington, North Carolina, when white supremacists overthrew the multi-racial government of state’s largest city through a campaign of violence and intimidation.

American Coup: Wilmington 1898 (español)

La historia poco conocida de la fatal masacre racial y del golpe de estado de 1898 en Wilmington, NC.

The American Vice President

What happens when the president is unable to serve? Explore the dramatic period between 1963 and 1976, when a grief-stricken, then scandal-stricken America was forced to define the role of the vice president and the process of succession.

Related Features

The Strike at Homestead Mill

The bitter conflict in 1892 at his steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania revealed Andrew Carnegie's conflicting beliefs regarding the rights of labor.

The Steel Business

Andrew Carnegie's relentless efforts to drive down costs and undersell the competition made his steel mills the models for the entire industry.

The Railroads

When Carnegie joined the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1853, trains carried a sense of wonder. At six cents a mile, a ride didn't come cheap, but it guaranteed a thrill.

American Experience Newsletter

- World Biography

Andrew Carnegie Biography

Born: November 25, 1835 Dunfermline, Scotland Died: August 11, 1919 Lenox, Massachusetts Scottish-born American industrialist and philanthropist

The Scottish-born American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie was the leader of the American steel industry from 1873 to 1901. He donated large sums of his fortune to educational, cultural, and scientific institutions.

Youth and early manhood

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, the son of William Carnegie, a weaver, and Margaret Morrison Carnegie. The invention of weaving machines replaced the work Carnegie's father did, and eventually the family was forced into poverty. In 1848 the family left Scotland and settled in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. Carnegie's father found a job in a cotton factory, but he soon quit to return to his home handloom, making linens and trying to sell them door to door. Carnegie also worked in the cotton factory, but after his father died in 1855, his strong desire to help take care of the family pushed him to educate himself. He became an avid reader, a theatergoer, and a lover of music.

Carnegie became a messenger boy for the Pittsburgh telegraph office. He later became a telegraph operator. Thomas A. Scott, superintendent of the western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, made the eighteen-year-old Carnegie his secretary. Carnegie was soon earning enough salary to buy a house for his mother. During the Civil War (1861–65), when Scott was named assistant secretary of war in charge of transportation, Carnegie helped organize the military telegraph system. But he soon returned to Pittsburgh to take Scott's old job with the railroad.

A future in steel

Between 1865 and 1870 Carnegie made money through investments in several small iron mills and factories. He also traveled throughout England, selling the bonds of small United States railroads and bridge companies. Carnegie began to see that steel was eventually going to replace iron for the manufacture of rails, structural shapes, pipe, and wire. In 1873 he organized a steel rail company. The first steel furnace at Braddock, Pennsylvania, began to roll rails in 1874. Carnegie continued building by cutting prices, driving out competitors, shaking off weak partners, and putting earnings back into the company. He never went public (sold shares of his company in order to raise money). Instead he obtained capital (money) from profits—and, when necessary, from local banks—and he kept on growing, making heavy steel alone. By 1878 the company was valued at $1.25 million.

Carnegie spent his leisure time traveling. He also wrote several books, including Triumphant Democracy (1886), which pointed out the advantages of American life over the unequal societies of Britain and other European countries. To Carnegie access to education was the key to America's political stability and industrial accomplishments. In 1889 he published an article, "Wealth," stating his belief that rich men had a duty to use their money to improve the welfare of the community. Carnegie remained a bachelor until his mother died in 1886. A year later he married Louise Whitfield. They had one child together. The couple began to spend six months each year in Scotland, though Carnegie kept an eye on business developments and problems.

Trials of the 1890s

Carnegie's absence from the United States was a factor in the Homestead mill strike of 1892. After acquiring Homestead, Carnegie had invested in new plants and equipment, increased production, and automated many of the mill's operations, cutting down the number of workers that were needed. These workers belonged to a union, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, with which the Carnegie Company had established wage and work agreements on a three-year basis. Carnegie believed that workers had a right to bargain with management through their unions. He also recognized the right to strike, as long as the action was conducted peacefully. He viewed strikes as trials of strength, with peaceful discussion resolving the conflict.

In contract talks during 1892, Frick wanted to lower the minimum wage because of the need for fewer workers. The union would not accept this and organized a strike. Carnegie was in Scotland, but he had instructed Frick that if a strike occurred the plant was to be shut down. Frick decided to smash the union by hiring people from the Pinkerton Agency as replacement workers and by trying to open the company properties by force. Two barges carrying three hundred Pinkertons moved up the Monongahela River and were shot at from the shore. The Pinkertons fired back, but they eventually surrendered. Five strikers and three Pinkertons were killed, and there were many injuries. The strikers had won; the company property remained closed. Five days later the governor of Pennsylvania sent in soldiers to restore order and open the plant. The soldiers were eventually withdrawn, and two months later the union called off the strike. Carnegie was criticized for his lack of action.

In the 1890s Carnegie also began to meet with tougher competition from newer, bigger companies who were interested in controlled prices and sharing the market. Companies that he had sold to for years threatened to cut down their purchases unless he agreed to cooperate. These threats made him decide to fight back. He refused to enter into any agreements with other companies. Moreover, he decided to invade their territories by making similar products and by expanding his sales activities into the West. Eventually, though, he decided to sell his company to the newly formed U.S. Steel Corporation in 1901 for almost $500 million. Carnegie's personal share was $225 million.

Carnegie's philanthropy

In retirement, Carnegie began to set up trust funds "for the improvement of mankind." He built some three thousand public libraries all over the English-speaking world. In 1895 the Carnegie Institute of Pittsburgh was opened, housing an art gallery, a natural history museum, and a music hall. He also built a group of technical schools that make up the present-day Carnegie Mellon University. The Carnegie Institution of Washington was set up to encourage research in the natural and physical sciences. Carnegie Hall was built in New York City. The Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching was created to provide pensions for university professors. Carnegie also established the Endowment for International Peace to seek an end to war.

In all, Carnegie's donations totaled $350 million. The continuation of his broad interests was put under the general charge of the Carnegie Corporation, with a donation of $125 million. Carnegie died on August 11, 1919, at his summer home near Lenox, Massachusetts.

For More Information

Carnegie, Andrew. The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920.

Hacker, Louis M. The World of Andrew Carnegie, 1865–1901. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1968.

Livesay, Harold C. Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business. Boston: Little, Brown, 1975.

Wall, Joseph F. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- American History ›

- The Gilded Age ›

Biography of Andrew Carnegie, Steel Magnate

Underwood Archive / Getty Images

- The Gilded Age

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Andrew Carnegie (November 25, 1835–August 11, 1919) was a steel magnate, leading industrialist, and philanthropist. With a keen focus on cost-cutting and organization, Carnegie was often regarded as a ruthless robber baron , though he eventually withdrew from business to devote himself to donating money to various philanthropic causes.

Fast Facts: Andrew Carnegie

- Known For : Carnegie was a preeminent steel magnate and a major philanthropist.

- Born : November 25, 1835 in Drumferline, Scotland

- Parents : Margaret Morrison Carnegie and William Carnegie

- Died : August 11, 1919 in Lenox, Massachusetts

- Education : Free School in Dunfermline, night school, and self-taught through Colonel James Anderson's library

- Published Works : An American Four-in-hand in Britain, Triumphant Democracy, The Gospel of Wealth, The Empire of Business, Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

- Awards and Honors : Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Glasgow, honorary doctorate, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. The following are all named for Andrew Carnegie: the dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii , the cactus Carnegiea gigantea , the Carnegie Medal children’s literature award, Carnegie Hall in New York City, Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

- Spouse(s) : Louise Whitfield

- Children : Margaret

- Notable Quote : “A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.”

Andrew Carnegie was born at Drumferline, Scotland on November 25, 1835. When Andrew was 13, his family emigrated to America and settled near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father had worked as a linen weaver in Scotland and pursued that work in America after first taking a job in a textile factory.

Young Andrew worked in the textile factory, replacing bobbins. He then took a job as a telegraph messenger at the age of 14, and within a few years was working as a telegraph operator. He educated himself through his voracious reading, benefitting from the generosity of a local retired merchant, Colonel James Anderson, who opened his small library to "working boys." Ambitious at work, Carnegie was promoted to be an assistant to an executive with the Pennsylvania Railroad by the age of 18.

During the Civil War , Carnegie, working for the railroad, helped the federal government set up a military telegraph system, which became vital to the war effort. For the duration of the war, he worked for the railroad.

Early Business Success

While working in the telegraph business, Carnegie began investing in other businesses. He invested in several small iron companies, a company that made bridges, and a manufacturer of railroad sleeping cars. Taking advantage of oil discoveries in Pennsylvania, Carnegie also invested in a small petroleum company.

By the end of the war, Carnegie was prosperous from his investments and began to harbor greater business ambitions. Between 1865 and 1870, he took advantage of the increase in international business following the war. He traveled frequently to England, selling the bonds of American railroads and other businesses. It has been estimated that he became a millionaire from his commissions selling bonds.

While in England, he followed the progress of the British steel industry. He learned everything he could about the new Bessemer process , and with that knowledge, he became determined to focus on the steel industry in America.

Carnegie had absolute confidence that steel was the product of the future. And his timing was perfect. As America industrialized, putting up factories, new buildings, and bridges, he was perfectly situated to produce and sell the steel the country needed.

Carnegie the Steel Magnate

In 1870, Carnegie established himself in the steel business. Using his own money, he built a blast furnace. He created a company in 1873 to make steel rails using the Bessemer process. Though the country was in an economic depression for much of the 1870s, Carnegie prospered.

A very tough businessman, Carnegie undercut competitors and was able to expand his business to the point where he could dictate prices. He kept reinvesting in his own company, and though he took in minor partners, he never sold stock to the public. He could control every facet of the business, and he did it with a fanatical eye for detail.

In the 1880s, Carnegie bought out Henry Clay Frick’s company, which owned coal fields as well as a large steel mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Frick and Carnegie became partners. As Carnegie began to spend half of every year at an estate in Scotland, Frick stayed in Pittsburgh, running the day-to-day operations of the company.

The Homestead Strike

Carnegie began to face a number of problems by the 1890s. Government regulation, which had never been an issue, was being taken more seriously as reformers actively tried to curtail the excesses of businessmen known as "robber barons."

The union which represented workers at the Homestead Mill went on strike in 1892. On July 6, 1892, while Carnegie was in Scotland, Pinkerton guards on barges attempted to take over the steel mill at Homestead.

The striking workers were prepared for the attack by the Pinkertons, and a bloody confrontation resulted in the death of strikers and Pinkertons. Eventually, an armed militia had to take over the plant.

Carnegie was informed by transatlantic cable of the events in Homestead. But he made no statement and did not get involved. He would later be criticized for his silence, and he later expressed regrets for his inaction. His opinions on unions, however, never changed. He fought against organized labor and was able to keep unions out of his plants during his lifetime.

As the 1890s continued, Carnegie faced competition in business, and he found himself being squeezed by tactics similar to those he had employed years earlier. In 1901, tired of business battles, Carnegie sold his interests in the steel industry to J.P. Morgan, who formed the United States Steel Corporation. Carnegie began to devote himself entirely to giving away his wealth.

Carnegie’s Philanthropy

Carnegie had already been giving money to create museums, such as the Carnegie Institute of Pittsburgh. But his philanthropy accelerated after selling Carnegie Steel. Carnegie supported numerous causes, including scientific research, educational institutions, museums, and world peace. He is best known for funding more than 2,500 libraries throughout the English-speaking world, and, perhaps, for building Carnegie Hall, a performance hall that has become a beloved New York City landmark.

Carnegie died of bronchial pneumonia at his summer home in Lenox, Massachusetts on August 11, 1919. At the time of his death, he had already given away over a large portion of his wealth, more than $350 million.

While Carnegie was not known to be openly hostile to the rights of workers for much of his career, his silence during the notorious and bloody Homestead Steel Strike cast him in a very bad light in labor history.

Carnegie's philanthropy left a huge mark on the world, including the endowment of many educational institutions and the funding of research and world peace efforts. The library system he helped form is a foundation of American education and democracy.

- “ Andrew Carnegie's Story .” Carnegie Corporation of New York .

- Carnegie, Andrew. Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. PublicAffairs, 1919.

- Carnegie, Andrew. The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1962.

- Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie . Penguin Group, 2006.

- Robber Barons

- Overview of the Second Industrial Revolution

- The Wall Street War to Control the Erie Railroad

- Financial Panics of the 19th Century

- Biography of Jacob Riis

- Tammany Hall

- August Belmont

- Biography of Jay Gould, Notorious Robber Baron

- Biography of Jim Fisk, Notorious Robber Baron

- The Great Chicago Fire of 1871

- The Credit Mobilier Scandal

- The Volcanic Eruption at Krakatoa

- Frederic Tudor

- First National Park Resulted From the Yellowstone Expedition

- The Conservation Movement in America

- The Five Points: New York's Most Notorious Neighborhood

Andrew Carnegie

The Father of Philanthropy

The Andrew Carnegie Collection is a join effort of the Carnegie Mellon University Libraries and the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. This work is funded by a grant from LSTA.

Contact: Julia Corrin

Andrew Carnegie: Biography

Andrew Carnegie, the most contradictory of the robber barons: he supported workers’ rights, but destroyed unions; and when he acquired the largest fortune in US history, he tried to give it away.

Andrew is born in Scotland in 1835. After steam power makes his textile worker father redundant, the family emigrate. He starts work aged 12, and soon his intelligence secures him a PA position to Pittsburgh rail road President, Tom Scott.

When his father dies, Andrew, now 20, becomes the main family breadwinner. Thankfully, he excels at work with innovations such as keeping the telegraph office open 24 hours a day. He’s promoted to manager and oversees railway expansion west.

Like many of the rich, he avoids fighting during the Civil War by paying a replacement to fight for him.

A BRIDGE TOO FAR? In 1868, Carnegie employs James Eads, a designer with no bridge building experience, to span the Mississippi at St Louis, Missouri. It will need to be over a mile long, bigger than anything built before it. But if it succeeds, it will connect East and West like never before. One in four bridges built at the time fail. Carnegie invests everything. But the traditional metal, iron, wouldn’t have the tensile strength to withstand the weight of freight carried over the bridge. Steel, the strongest material ever produced (made by mixing iron with carbon at over 2,000 degrees) is however, difficult to mass produce and extremely expensive. At the time, it’s used in small quantities for designer items such as cutlery and jewellery.

Carnegie spends years searching for an answer and eventually finds an English inventor, Henry Bessemer, in Sheffield. With his mass-production solution the time it takes to make a single rail goes from two weeks to 15 minutes. Even so, Carnegie falls years behind schedule and is nearly buried in debt.

"If you can't embrace failure, you can't be widely successful...It's an axiomatic truth." Donny Deutsch, Advertising Mogul

But in 1873, aged just 33, Carnegie unites America with the opening of the St Louis bridge. He still needs to convince people it’s safe to traverse and as there’s a myth that elephants won’t cross unstable structures, he has one walk across it on opening day.

Steel orders flood in as the railroad owners seek to replace their tracks with the stronger material. With his old mentor Tom Scott’s help, Carnegie raises $21m in today’s money and builds his first steel plant. The 100 acre steel mill is the country’s largest capable of producing 225 tonnes a day. But when Rockefeller moves his oil off the railroads, he bursts the bubble in the rail road industry. Carnegie suffers in the subsequent stock market crash, but not as much Tom Scott.

Disgruntled workers burn Scott’s business down and help to send him to an early grave. So when, in 1881, Carnegie buries his mentor on a rainy day in April, he blames Rockefeller for Scott’s demise and seeks revenge. He’s now producing 10,000 tons of steel a month and making $1.5 million profits per year.

STEEL SKIES And Carnegie finds another massive market. Manhattan land is the most expensive in the world. The only way to expand is up, but materials and current technology mean few buildings exceed five floors. Steel solves this. The first Chicago skyscraper is built with Carnegie steel.

"America grew up vertically on steel" Alan Greenspan, Former Chairman, Federal Reserve

But despite his newfound wealth making him one of the richest men in America, Rockefeller is still worth seven times more than Carnegie. He hires Henry Frick, a self made millionaire by 30, one of the Midwest’s largest coal suppliers and a ruthless businessman. In two years, Frick doubles Carnegie’s profits.

JOHNSTOWN To celebrate, Frick sets up a resort for the super-rich: the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club and his business partner is soon one of its members. It is in a superb location, situated near the South Fork dam. This dam holds 20 million tonnes of water. Fourteen miles downriver sits Johnstown. Frick orders the dam lowered (in order to make it possible for his carriage to travel along the top) and the reservoir water level to be raised. This, combined with one day’s heavy rainfall on 31 May 1899, that pushes the water level up by an inch every ten minutes, these actions prove fatal.

“Prepare for the worst” South Fork Dam Telegraph to Johnstown

The dam bursts and more than 2,000 people are killed. One in three are so mutilated that they are never identified. 16,000 homes are destroyed and four square miles are levelled. The recently formed Red Cross is called. It’s the worst manmade disaster in American history, prior to 9/11.

Members of The South Fork are sued, unsuccessfully. But Carnegie feels responsible and donates millions to rebuild Johnstown. Despite Rockefeller still being worth three times more than Carnegie, the Scotsman donates ever increasing amounts of his fortune.

HOMESTEAD Carnegie invests millions to turn around the Homestead Steel Works, a struggling steel mill outside Pittsburgh, to increase the production of structural steel. But to cut costs, Carnegie allows Frick to increase working hours and reduce wages. When the newly formed unions start opposing 12 hour days and six day weeks, and the subsequent workplace injuries and fatalities, Frick writes to Carnegie asking for permission to crush them. In the wake of the Johnstown tragedy, Carnegie has retreated to his homeland, Scotland, and essentially leaves it to Frick.

"Carnegie didn’t enjoy being the bad guy, being the villain. Frick didn’t seem to mind." DAVID NASAW, Carnegie biographer

Frick stockpiles steel in preparation for a strike. He brings in the Pinkerton Detectives, a private army willing to track down train robbers, guard the President and break strikes. In 1892, two thousand workers barricade themselves inside the Homestead plant, stopping steel production. In the escalating tension, The Pinkertons fire on the unarmed workers. Many are shot in the back as they run for their lives. Nine are killed. The strike is broken, but not until the state governor sends in the state militia. Frick, seen as the cause of the trouble, is shot and stabbed by an anarchist assassin. But three days after this attempted assassination, he’s back at work and moreover, hustling to take the steel plants away from Carnegie. He fails and Carnegie instructs his board to eject Frick.

EVERY MAN HAS HIS PRICE JP Morgan approaches Carnegie and asks him to sell. At a dinner party, Carnegie writes out four hundred and eighty million on a piece of paper. The equivalent today of four hundred billion dollars, or the entire budget of the US Federal Government. In modern terms Carnegie has amassed a personal fortune of over $310 billion. The largest private fortune the world has ever seen.

Carnegie spends the rest of his life giving away more than 350 million dollars, or 67 billion in today’s money. But despite his charitable efforts, the tragedies of Johnstown and Homestead were associated with his name until his death, from bronchial pneumonia, in 1919.

Most Recent

The short but heroic life of Violette Szabo

A Nazi Christmas: Redefining tradition under the Third Reich

Mari Lwyd: Wales’ skeletal Christmas horse

Top 10 Viking weapons

More from history.

The original January 6th: When British forces invaded Washington

Take heart: Bloody execution in the Americas from the Aztecs to the Incas

Surprising family links of US Presidents

What if JFK was never assassinated?

Keep reading.

Who Survived the Alamo?

Facts About Louisiana

Hillary Clinton: 9 Interesting Facts

Custer's ego came out on top

You might be interested in.

6 Things you didn't know about the CIA

Presidential scandals throughout history

10 things you didn't know about Roosevelt

The Unsung Heroes of 9/11

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Andrew Carnegie was born to Margaret (Morrison) Carnegie and William Carnegie in Dunfermline, Scotland, [10] in a typical weaver's cottage with only one main room. It consisted of half the ground floor, which was shared with the neighboring weaver's family. [ 11 ]

Apr 3, 2014 · Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Although he had little formal education, Carnegie grew up in a family that believed in the importance of books and ...

Nov 9, 2009 · Andrew Carnegie, whose life became a rags-to-riches story, was born into modest circumstances on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, the second of two sons of Will, a handloom weaver, and ...

Carnegie lived for another five years, but the last entry in his autobiography was the day World War I began. By the time of Carnegie's death in 1919, he had given away $350 million ($4.4 billion ...

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, the son of William Carnegie, a weaver, and Margaret Morrison Carnegie. The invention of weaving machines replaced the work Carnegie's father did, and eventually the family was forced into poverty.

Jul 8, 2019 · Andrew Carnegie (November 25, 1835–August 11, 1919) was a steel magnate, leading industrialist, and philanthropist. With a keen focus on cost-cutting and organization, Carnegie was often regarded as a ruthless robber baron, though he eventually withdrew from business to devote himself to donating money to various philanthropic causes.

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) was among the most famous and wealthy industrialists of his day. Through the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the innovative philanthropic foundation he established in 1911, his fortune has since supported everything from the discovery of insulin and the dismantling of nuclear weapons, to the creation of Sesame Street and the Common Core Standards.

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835 to William Carnegie and Margaret Morrison Carnegie in Dunfermline, Scotland. His father was a weaver and moved the entire family to Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, in 1848 after industrialization phase that rendered him jobless and in relentless poverty.

Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland in 1835. Andrew’s family was not rich but they were very smart and Andrew was encouraged to read and learn and voice his opinions. His father, William, was a weaver who made a good living until 1847 when Dunfermline opened to cloth factories using steam powered looms.

Andrew Carnegie, the most contradictory of the robber barons: he supported workers’ rights, but destroyed unions; and when he acquired the largest fortune in US history, he tried to give it away. Andrew is born in Scotland in 1835. After steam power makes his textile worker father redundant, the family emigrate.