Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

- Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

Academic Experience

How to write great survey questions (with examples)

Learning how to write survey questions is both art and science. The wording you choose can make the difference between accurate, useful data and just the opposite. Fortunately, we’ve got a raft of tips to help.

Figuring out how to make a good survey that yields actionable insights is all about sweating the details. And writing effective questionnaire questions is the first step.

Essential for success is understanding the different types of survey questions and how they work. Each format needs a slightly different approach to question-writing.

In this article, we’ll share how to write survey questionnaires and list some common errors to avoid so you can improve your surveys and the data they provide.

Free eBook: The Qualtrics survey template guide

Survey question types

Did you know that Qualtrics provides 23 question types you can use in your surveys ? Some are very popular and used frequently by a wide range of people from students to market researchers, while others are more specialist and used to explore complex topics. Here’s an introduction to some basic survey question formats, and how to write them well.

Multiple choice

Familiar to many, multiple choice questions ask a respondent to pick from a range of options. You can set up the question so that only one selection is possible, or allow more than one to be ticked.

When writing a multiple choice question…

- Be clear about whether the survey taker should choose one (“pick only one”) or several (“select all that apply”).

- Think carefully about the options you provide, since these will shape your results data.

- The phrase “of the following” can be helpful for setting expectations. For example, if you ask “What is your favorite meal” and provide the options “hamburger and fries”, “spaghetti and meatballs”, there’s a good chance your respondent’s true favorite won’t be included. If you add “of the following” the question makes more sense.

Asking participants to rank things in order, whether it’s order of preference, frequency or perceived value, is done using a rank structure. There can be a variety of interfaces, including drag-and-drop, radio buttons, text boxes and more.

When writing a rank order question…

- Explain how the interface works and what the respondent should do to indicate their choice. For example “drag and drop the items in this list to show your order of preference.”

- Be clear about which end of the scale is which. For example, “With the best at the top, rank these items from best to worst”

- Be as specific as you can about how the respondent should consider the options and how to rank them. For example, “thinking about the last 3 months’ viewing, rank these TV streaming services in order of quality, starting with the best”

Slider structures ask the respondent to move a pointer or button along a scale, usually a numerical one, to indicate their answers.

When writing a slider question…

- Consider whether the question format will be intuitive to your respondents, and whether you should add help text such as “click/tap and drag on the bar to select your answer”

- Qualtrics includes the option for an open field where your respondent can type their answer instead of using a slider. If you offer this, make sure to reference it in the survey question so the respondent understands its purpose.

Also known as an open field question, this format allows survey-takers to answer in their own words by typing into the comments box.

When writing a text entry question…

- Use open-ended question structures like “How do you feel about…” “If you said x, why?” or “What makes a good x?”

- Open-ended questions take more effort to answer, so use these types of questions sparingly.

- Be as clear and specific as possible in how you frame the question. Give them as much context as you can to help make answering easier. For example, rather than “How is our customer service?”, write “Thinking about your experience with us today, in what areas could we do better?”

Matrix table

Matrix structures allow you to address several topics using the same rating system, for example a Likert scale (Very satisfied / satisfied / neither satisfied nor dissatisfied / dissatisfied / very dissatisfied).

When writing a matrix table question…

- Make sure the topics are clearly differentiated from each other, so that participants don’t get confused by similar questions placed side by side and answer the wrong one.

- Keep text brief and focused. A matrix includes a lot of information already, so make it easier for your survey-taker by using plain language and short, clear phrases in your matrix text.

- Add detail to the introductory static text if necessary to help keep the labels short. For example, if your introductory text says “In the Philadelphia store, how satisfied were you with the…” you can make the topic labels very brief, for example “staff friendliness” “signage” “price labeling” etc.

Now that you know your rating scales from your open fields, here are the 7 most common mistakes to avoid when you write questions. We’ve also added plenty of survey question examples to help illustrate the points.

Likert Scale Questions

Likert scales are commonly used in market research when dealing with single topic survyes. They're simple and most reliable when combatting survey bias . For each question or statement, subjects choose from a range of possible responses. The responses, for example, typically include:

- Strongly agree

- Strongly disagree

7 survey question examples to avoid.

There are countless great examples of writing survey questions but how do you know if your types of survey questions will perform well? We've highlighted the 7 most common mistakes when attempting to get customer feedback with online surveys.

Survey question mistake #1: Failing to avoid leading words / questions

Subtle wording differences can produce great differences in results. For example, non-specific words and ideas can cause a certain level of confusing ambiguity in your survey. “Could,” “should,” and “might” all sound about the same, but may produce a 20% difference in agreement to a question.

In addition, strong words such as “force” and “prohibit” represent control or action and can bias your results.

Example: The government should force you to pay higher taxes.

No one likes to be forced, and no one likes higher taxes. This agreement scale question makes it sound doubly bad to raise taxes. When survey questions read more like normative statements than questions looking for objective feedback, any ability to measure that feedback becomes difficult.

Wording alternatives can be developed. How about simple statements such as: The government should increase taxes, or the government needs to increase taxes.

Example: How would you rate the career of legendary outfielder Joe Dimaggio?

This survey question tells you Joe Dimaggio is a legendary outfielder. This type of wording can bias respondents.

How about replacing the word “legendary” with “baseball” as in: How would you rate the career of baseball outfielder Joe Dimaggio? A rating scale question like this gets more accurate answers from the start.

Survey question mistake #2: Failing to give mutually exclusive choices

Multiple choice response options should be mutually exclusive so that respondents can make clear choices. Don’t create ambiguity for respondents.

Review your survey and identify ways respondents could get stuck with either too many or no single, correct answers to choose from.

Example: What is your age group?

What answer would you select if you were 10, 20, or 30? Survey questions like this will frustrate a respondent and invalidate your results.

Example: What type of vehicle do you own?

This question has the same problem. What if the respondent owns a truck, hybrid, convertible, cross-over, motorcycle, or no vehicle at all?

Survey question mistake #3: Not asking direct questions

Questions that are vague and do not communicate your intent can limit the usefulness of your results. Make sure respondents know what you’re asking.

Example: What suggestions do you have for improving Tom’s Tomato Juice?

This question may be intended to obtain suggestions about improving taste, but respondents will offer suggestions about texture, the type of can or bottle, about mixing juices, or even suggestions relating to using tomato juice as a mixer or in recipes.

Example: What do you like to do for fun?

Finding out that respondents like to play Scrabble isn’t what the researcher is looking for, but it may be the response received. It is unclear that the researcher is asking about movies vs. other forms of paid entertainment. A respondent could take this question in many directions.

Survey question mistake #4: Forgetting to add a “prefer not to answer” option

Sometimes respondents may not want you to collect certain types of information or may not want to provide you with the types of information requested.

Questions about income, occupation, personal health, finances, family life, personal hygiene, and personal, political, or religious beliefs can be too intrusive and be rejected by the respondent.

Privacy is an important issue to most people. Incentives and assurances of confidentiality can make it easier to obtain private information.

While current research does not support that PNA (Prefer Not to Answer) options increase data quality or response rates, many respondents appreciate this non-disclosure option.

Furthermore, different cultural groups may respond differently. One recent study found that while U.S. respondents skip sensitive questions, Asian respondents often discontinue the survey entirely.

- What is your race?

- What is your age?

- Did you vote in the last election?

- What are your religious beliefs?

- What are your political beliefs?

- What is your annual household income?

These types of questions should be asked only when absolutely necessary. In addition, they should always include an option to not answer. (e.g. “Prefer Not to Answer”).

Survey question mistake #5: Failing to cover all possible answer choices

Do you have all of the options covered? If you are unsure, conduct a pretest version of your survey using “Other (please specify)” as an option.

If more than 10% of respondents (in a pretest or otherwise) select “other,” you are probably missing an answer. Review the “Other” text your test respondents have provided and add the most frequently mentioned new options to the list.

Example: You indicated that you eat at Joe's fast food once every 3 months. Why don't you eat at Joe's more often?

There isn't a location near my house

I don't like the taste of the food

Never heard of it

This question doesn’t include other options, such as healthiness of the food, price/value or some “other” reason. Over 10% of respondents would probably have a problem answering this question.

Survey question mistake #6: Not using unbalanced scales carefully

Unbalanced scales may be appropriate for some situations and promote bias in others.

For instance, a hospital might use an Excellent - Very Good - Good - Fair scale where “Fair” is the lowest customer satisfaction point because they believe “Fair” is absolutely unacceptable and requires correction.

The key is to correctly interpret your analysis of the scale. If “Fair” is the lowest point on a scale, then a result slightly better than fair is probably not a good one.

Additionally, scale points should represent equi-distant points on a scale. That is, they should have the same equal conceptual distance from one point to the next.

For example, researchers have shown the points to be nearly equi-distant on the strongly disagree–disagree–neutral–agree–strongly agree scale.

Set your bottom point as the worst possible situation and top point as the best possible, then evenly spread the labels for your scale points in-between.

Example: What is your opinion of Crazy Justin's auto-repair?

Pretty good

The Best Ever

This question puts the center of the scale at fantastic, and the lowest possible rating as “Pretty Good.” This question is not capable of collecting true opinions of respondents.

Survey question mistake #7: Not asking only one question at a time

There is often a temptation to ask multiple questions at once. This can cause problems for respondents and influence their responses.

Review each question and make sure it asks only one clear question.

Example: What is the fastest and most economical internet service for you?

This is really asking two questions. The fastest is often not the most economical.

Example: How likely are you to go out for dinner and a movie this weekend?

Dinner and Movie

Dinner Only

Even though “dinner and a movie” is a common term, this is two questions as well. It is best to separate activities into different questions or give respondents these options:

5 more tips on how to write a survey

Here are 5 easy ways to help ensure your survey results are unbiased and actionable.

1. Use the Funnel Technique

Structure your questionnaire using the “funnel” technique. Start with broad, general interest questions that are easy for the respondent to answer. These questions serve to warm up the respondent and get them involved in the survey before giving them a challenge. The most difficult questions are placed in the middle – those that take time to think about and those that are of less general interest. At the end, we again place general questions that are easier to answer and of broad interest and application. Typically, these last questions include demographic and other classification questions.

2. Use “Ringer” questions

In social settings, are you more introverted or more extroverted?

That was a ringer question and its purpose was to recapture your attention if you happened to lose focus earlier in this article.

Questionnaires often include “ringer” or “throw away” questions to increase interest and willingness to respond to a survey. These questions are about hot topics of the day and often have little to do with the survey. While these questions will definitely spice up a boring survey, they require valuable space that could be devoted to the main topic of interest. Use this type of question sparingly.

3. Keep your questionnaire short

Questionnaires should be kept short and to the point. Most long surveys are not completed, and the ones that are completed are often answered hastily. A quick look at a survey containing page after page of boring questions produces a response of, “there is no way I’m going to complete this thing”. If a questionnaire is long, the person must either be very interested in the topic, an employee, or paid for their time. Web surveys have some advantages because the respondent often can't view all of the survey questions at once. However, if your survey's navigation sends them page after page of questions, your response rate will drop off dramatically.

How long is too long? The sweet spot is to keep the survey to less than five minutes. This translates into about 15 questions. The average respondent is able to complete about 3 multiple choice questions per minute. An open-ended text response question counts for about three multiple choice questions depending, of course, on the difficulty of the question. While only a rule of thumb, this formula will accurately predict the limits of your survey.

4. Watch your writing style

The best survey questions are always easy to read and understand. As a rule of thumb, the level of sophistication in your survey writing should be at the 9th to 11th grade level. Don’t use big words. Use simple sentences and simple choices for the answers. Simplicity is always best.

5. Use randomization

We know that being the first on the list in elections increases the chance of being elected. Similar bias occurs in all questionnaires when the same answer appears at the top of the list for each respondent. Randomization corrects this bias by randomly rotating the order of the multiple choice matrix questions for each respondent.

While not totally inclusive, these seven survey question tips are common offenders in building good survey questions. And the five tips above should steer you in the right direction.

Focus on creating clear questions and having an understandable, appropriate, and complete set of answer choices. Great questions and great answer choices lead to great research success. To learn more about survey question design, download our eBook, The Qualtrics survey template guide or get started with a free survey account with our world-class survey software .

Sarah Fisher

Related Articles

February 8, 2023

Smoothing the transition from school to work with work-based learning

December 6, 2022

How customer experience helps bring Open Universities Australia’s brand promise to life

August 9, 2022

3 things that will improve your teachers’ school experience

August 2, 2022

Why a sense of belonging at school matters for K-12 students

July 14, 2022

Improve the student experience with simplified course evaluations

March 17, 2022

Understanding what’s important to college students

February 18, 2022

Malala: ‘Education transforms lives, communities, and countries’

July 8, 2020

5 challenges in getting back to school (and 5 ways to tackle them)

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

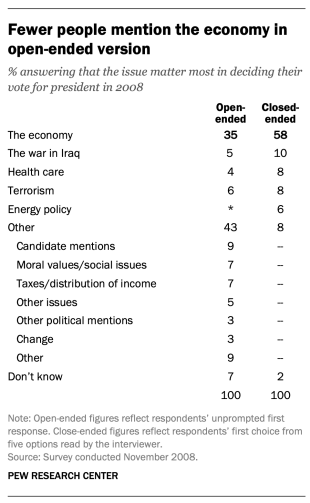

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

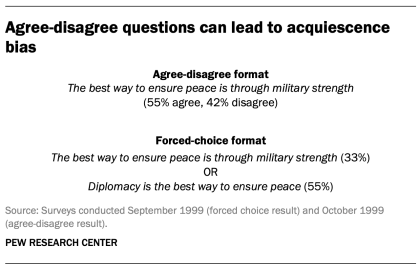

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

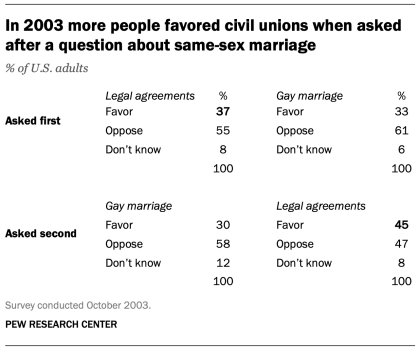

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

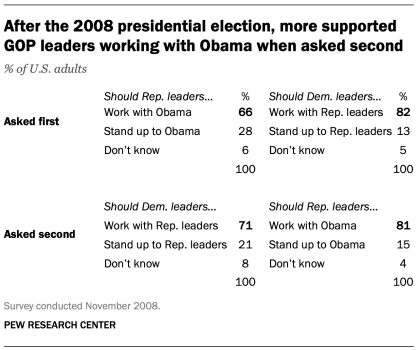

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Survey Questions 101: 70+ Survey Question Examples, Types of Surveys, and FAQs

Want to create surveys that actually get results? The key lies in crafting the perfect questions. Surveys are a powerful tool for collecting data, understanding opinions, and making informed decisions. And the effectiveness of your survey largely depends on the quality of your survey questions . Let’s explore the types of survey questions , a list of survey question examples , and address frequently asked questions to help you design impactful surveys.

Understanding Survey Questions

Survey questions are designed to elicit specific responses from participants. They play a crucial role in gathering the data you need. The quality and relevance of these questions can significantly impact the insights you gain from your survey. Properly crafted survey questions lead to more accurate and actionable data.

Types of Survey Questions

To create effective surveys, it’s essential to understand the different types of survey questions available. Each type serves a distinct purpose and helps in gathering different kinds of information.

1. Multiple-Choice Questions

Multiple-choice questions are among the most common types. They offer respondents a set of predefined answers to choose from.

- Example : “Which of the following features do you value the most in a smartphone? A) Battery life B) Camera quality C) Screen size D) Processor speed”

2. Likert Scale Questions

Likert scale questions measure the extent of agreement or disagreement with a statement. They are useful for gauging attitudes and opinions.

- Example : “How satisfied are you with our customer service? A) Very dissatisfied B) Dissatisfied C) Neutral D) Satisfied E) Very satisfied”

3. Rating Scale Questions

Rating scale questions ask respondents to rate a particular item or service on a scale, often from 1 to 10.

- Example : “On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate the usability of our website?”

4. Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions allow respondents to provide detailed, qualitative responses. They are ideal for exploring opinions and experiences.

- Example : “What improvements would you like to see in our product?”

5. Dichotomous Questions

Dichotomous questions offer only two response options, such as yes/no or true/false.

- Example : “Did you find the information you were looking for on our website? Yes/No”

6. Demographic Questions

Demographic questions collect information about the respondent’s background, such as age, gender, income, and education level.

- Example : “What is your highest level of education? A) High school B) Associate’s degree C) Bachelor’s degree D) Master’s degree E) Doctorate”

Survey Question Examples

To help you get started, here’s a diverse list of survey question examples that can be tailored to different types of surveys.

Product Survey Questions

- “How likely are you to recommend our product to a friend or colleague? (1 being ‘Not at all likely’ and 10 being ‘Extremely likely’)”

- “What features do you think are missing from our product?”

- “How does our product compare to similar products you’ve used?”

Customer Satisfaction Survey Questions

- “How would you rate your overall experience with our company?”

- “How easy was it to find what you were looking for on our website?”

- “How likely are you to purchase from us again?”

Employee Feedback Survey Questions

- “Do you feel valued by your team and manager?”

- “How would you rate the communication within your department?”

- “What changes would you suggest to improve employee satisfaction?”

Market Research Survey Questions

- “Which brand do you prefer for [specific product] and why?”

- “How much are you willing to spend on [specific product]?”

- “What factors influence your purchasing decisions the most?”

Best Survey Questions

The best survey questions are those that are clear, concise, and relevant to the objectives of the survey. Here are some tips to help you craft effective survey questions:

- Be Specific : Avoid vague questions. Make sure your questions are precise and focused on a single topic.

- Use Simple Language : Ensure that your questions are easily understandable by using straightforward language.

- Avoid Leading Questions : Frame questions in a neutral manner to avoid influencing respondents’ answers.

- Provide Balanced Options : When using multiple-choice questions, ensure that all options are relevant and balanced.

- Test Your Questions : Before deploying your survey, test your questions with a small group to identify any issues or ambiguities.

FAQs About Survey Questions

What makes a good survey question.

A good survey question is clear, concise, and directly related to the survey’s objective. It should be easy to understand and answer, avoiding any leading or biased language.

How Many Questions Should a Survey Have?

The number of questions in a survey depends on its purpose. A short survey may have 5-10 questions, while a more comprehensive survey could have 20 or more. Keep in mind that longer surveys may lead to lower response rates, so focus on quality over quantity.

How Can I Improve Survey Response Rates?

To improve response rates, ensure that your survey is easy to complete and offers incentives if possible. Make the survey accessible on various devices and keep the questions relevant to the target audience.

What Are Some Common Mistakes to Avoid in Surveys?

Common mistakes include using leading or biased questions, making questions too complex, and failing to pre-test the survey. Not providing adequate instructions or options for responses can lead to inaccurate data.

How Should I Analyze Survey Data?

After collecting survey responses, analyze the data by looking for patterns and trends. Use statistical tools and software to generate reports and visualize the data. Interpret the results in the context of your survey objectives to draw meaningful conclusions.

Creating effective surveys involves understanding and utilizing various types of survey questions to gather valuable insights. By incorporating a range of survey question examples , from product survey questions to customer satisfaction queries, you can collect data that drives informed decisions. Remember to design your survey with clarity and precision to obtain the most accurate and actionable results. With the right approach and attention to detail, you’ll be able to leverage the best survey questions to achieve your objectives and gain a deeper understanding of your target audience.

For further guidance, consider experimenting with different question types and continuously refining your survey design based on feedback and results. This iterative process will help you create surveys that are not only effective but also engaging for your respondents.

You have scrolled so far, don't stop now! Connect with our experts.

We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Cookie Policy

Necessary cookies help with the basic functionality of our website, e.g. remember if you gave consent to cookies.

Analytical cookies make it possible to gather statistics about the use and traffic on our website, so we can make it better.

Marketing cookies make it possible to show you more relevant social media content and advertisements on our website and other platforms.

First Name Last Name

Company Email

Company Name

Save 15% or more when you register for 3+ upcoming courses Until January 21

Writing Good Survey Questions: 10 Best Practices

August 20, 2023 2023-08-20

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

Unfortunately, there is no simple formula for cranking out good, unbiased questionnaires.

That said, there are certainly common mistakes in survey design that can be avoided if you know what to look for. Below, I’ve provided the 10 most common and dangerous errors that can be made when designing a survey and guidelines for how to avoid them.

In This Article:

1. ask about the right things, 2. use language that is neutral, natural, and clear, 3. don’t ask respondents to predict behavior, 4. focus on closed-ended questions, 5. avoid double-barreled questions, 6. use balanced scales, 7. answer options should be all-inclusive and mutually exclusive, 8. provide an opt-out, 9. allow most questions to be optional, 10. respect your respondents, ask only questions that you need answered.

One of the easiest traps to fall into when writing a survey is to ask about too much. After all, you want to take advantage of this one opportunity to ask questions of your audience, right?

The most important thing to remember about surveys is to keep them short . Ask only about the things that are essential for answering your research questions. If you don’t absolutely need the information, leave it out.

Don’t Ask Questions that You Can Find the Answer to

When drafting a survey, many researchers slip into autopilot and start by asking a plethora of demographic questions . Ask yourself: do you need all that demographic information? Will you use it to answer your research questions? Even if you will use it, is there another way to capture it besides asking about it in a survey? For example, if you are surveying current customers, and they are providing their email addresses, could you look up their demographic information if needed?

Don’t Ask Questions that Respondents Can’t Answer Accurately

Surveys are best for capturing quantitative attitudinal data . If you’re looking to learn something qualitative or behavioral, there’s likely a method better suited to your needs. Asking the question in a survey is, at best, likely to introduce inefficiency in your process, and, at worst, will produce unreliable or misleading data.

For example, consider the question below:

If I were asked this question, I could only speculate about what might make a button stand out. Maybe a large size? Maybe a different color, compared to surrounding content? But this is merely conjecture. The only reliable way to tell if the button actually stood out for me would be to mock up the page and show it to me. This type of question would be better studied with other research methods, such as usability testing or A/B testing , but not with a survey.

Avoid Biasing Respondents

There are endless ways in which bias can be introduced into survey data , and it is the researcher’s task to minimize this bias as much as possible. For example, consider the wording of the following question.

By initially providing the context that the organization is committed to achieving a 5-star satisfaction rating , the survey creators are, in essence, pleading with the respondent to give them one. The respondent may feel guilty providing an honest response if they had a less than stellar experience.

Note also the use of the word satisfaction . This wording subtly biases the participant into framing their experience as a satisfactory one.

An alternative wording of the question might remove the first sentence altogether, and simply ask respondents to rate their experience.

Use Natural, Familiar Language

We must always be on the lookout for jargon in survey design. If respondents cannot understand your questions or response options, you will introduce bad data into your dataset. While we should strive to keep survey questions short and simple, it is sometimes necessary to provide brief definitions or descriptions when asking about complex topics, to prevent misunderstanding. Always pilot your questionnaires with the target audience to ensure that all jargon has been removed.

Speak to Respondents Like Humans

For some reason, when drafting a questionnaire, many researchers introduce unnecessary formality and flowery language into their questions. Resist this urge. Phrase questions as clearly and simply as possible, as though you were asking them in an interview format.

People are notoriously unreliable predictors of their own behavior. For various reasons, predictions are almost bound to be flawed, leading Jakob Nielsen to remind us to never listen to users .

Yet, requests for behavioral predictions are rampant in insufficiently thought-out UX surveys. Consider the question: How likely are you to use this product? While a respondent may feel likely to use a product based on a description or a brief tutorial, their answer does not constitute a reliable prediction and should not be used to make critical product decisions.

Often, instead of future-prediction requests , you will see present-estimate requests : How often do you currently use this product in an average week? While this type of question avoids the problem of predictions, it still is unreliable. Users struggle to estimate based on some imaginary “average” week and will often, instead, recall outlier weeks, which are more memorable.

The best way to phrase a question like this is to ask for specific, recent memories : Approximately how many times did you use this product in the past 7 days? It is important to include the word approximately and to allow for ranges rather than exact numbers. Reporting an exact count of a past behavior is often either challenging or impossible, so asking for it introduces imprecise data. It can also make respondents more likely to drop off if they feel incapable of answering the question accurately.

Surveys are, at their core, a quantitative research method . They rely upon closed-ended questions (e.g., multiple-choice or rating-scale questions) to generate quantitative data. Surveys can also leverage open-ended questions (e.g., short-answer or long-answer questions) to generate qualitative data. That said, the best surveys rely upon closed-ended questions, with a smattering of open-ended questions to provide additional qualitative color and support to the mostly quantitative data.

If you find that your questionnaire relies overly heavily on open-ended questions, it might be a red flag that another qualitative-research method (e.g., interviews ) may serve your research aims better.

On the subject of open-ended survey questions, it is often wise to include one broad open-ended question at the end of your questionnaire . Many respondents will have an issue or piece of feedback in mind when they start a survey, and they’re simply waiting for the right question to come up. If no such question exists, they may end the survey experience with a bad taste. A final, optional, long-answer question with a prompt like Is there anything else you’d like to share? can help to alleviate this frustration and supply some potentially valuable data.

A double-barreled question asks respondents to answer two things at once. For example: How easy and intuitive was this website to use? Easy and intuitive , while related, are not synonymous, and, therefore, the question is asking the respondent to use a single rating scale to assess the website on two distinct dimensions simultaneously. By necessity, the respondent will either pick one of these words to focus on or try to assess both and estimate a midpoint “average” score. Neither of these will generate fully accurate or reliable data.

Therefore, double-barreled questions should always be avoided and, instead, split up into two separate questions.

Rating-scale questions are tremendously valuable in generating quantitative data in survey design. Often, a respondent is asked to rate their agreement with a statement on an agreement scale (e.g., Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree ), or otherwise to rate something using a scale of adjectives (e.g., Excellent, Good, Neutral, Fair, Poo r).

You’ll notice that, in both of the examples given above, there is an equal number of positive and negative options (2 each), surrounding a neutral option. The equal number of positive and negative options means that the response scale is balanced and eliminates a potential source of bias or error.

In an unbalanced scale, you’ll see an unequal number of positive and negative options (e.g., Excellent, Very Good, Good, Poor, Very Poor ). This example contains 3 positive options and only 2 negative ones. It, therefore, biases the participant to select a positive option.

Answer options for a multiple-choice question should include all possible answers (i.e., all inclusive) and should not overlap (i.e., mutually exclusive). For example, consider the following question:

In this formulation, some possible answers are skipped (i.e., anyone who is over 50 won’t be able to select an answer). Additionally, some answers overlap (e.g., a 20-year-old could select either the first or second response).

Always doublecheck your numeric answer options to ensure that all numbers are included and none are repeated .

No matter how carefully and inclusively you craft your questions, there will always be respondents for whom none of the available answers are acceptable. Maybe they are an edge case you hadn’t considered. Maybe they don’t remember the answer. Or maybe they simply don’t want to answer that particular question. Always provide an opt-out answer in these cases to avoid bad data.

Opt-out answers can include things like the following: Not applicable , None of the above , I don’t know, I don’t recall , Other , or Prefer not to answer . Any multiple-choice question should include at least one of these answers. However, avoid the temptation to include one catch-all opt-out answer containing multiple possibilities . For example, an option labeled I don’t know / Not applicable covers two very different responses with different meanings; combining them fogs your data.

It is so tempting to make questions required in a questionnaire. After all, we want the data! However, the choice to make any individual question required will likely lead to one of two unwanted results:

- Bad Data: If a respondent is unable to answer a question accurately, but the question is required, they may select an answer at random. These types of answers will be impossible to detect and will introduce bad data into your study, in the form of random-response bias.

- Dropoffs: The other option available to a participant unable to correctly answer a required question is to abandon the questionnaire. This behavior will increase the effort needed to reach the desired number of responses.

Therefore, before deciding to make any question required, consider if doing so is worth the risks of bad data and dropoffs.

In the field of user experience, we like to say that we are user advocates. That doesn’t just mean advocating for user needs when it comes to product decisions. It also means respecting our users any time we’re fortunate enough to interact with them.

Don’t Assume Negativity

This is particularly important when discussing health issues or disability. Phrasings such Do you suffer from hypertension? may be perceived as offensive. Instead, use objective wording such as Do you have hypertension?

Be Sensitive with Sensitive Topics

When asking about any topics that may be deemed sensitive, private, or offensive, first ask yourself: Does it really need to be asked? Often, we can get plenty of valuable information while omitting that topic.

Other times, it is necessary to delve into potentially sensitive topics. In these cases, be sure to choose your wording carefully. Ensure you’re using the current preferred terminology favored by members of the population you’re addressing. If necessary, consider providing a brief explanation for why you are asking about that particular topic and what benefit will come from responding.

Use Inclusive and Appropriate Wording for Demographic Questions

When asking about topics such as race, ethnicity, sex, or gender identity, use accurate and sensitive terminology. For example, it is no longer appropriate to offer a simple binary option for gender questions. At a minimum, a third option indicating an Other or Non-binary category is expected, as well as an opt-out answer for those that prefer not to respond.

An inclusive question is respectful of your users’ identities and allows them to answer only if they feel comfortable.

Related Courses

Survey design and execution.

Use surveys to drive and evaluate UX design

ResearchOps: Scaling User Research

Orchestrate and optimize research to amplify its impact

User Interviews

Uncover in-depth, accurate insights about your users

Related Topics

- Research Methods Research Methods

Learn More:

Wizard of Oz Method in UX

Sara Paul · 4 min

Sample Sizes for Qualitative Studies

Maria Rosala · 4 min

Unlock Powerful UX Insights with Custom Events in Analytics

Tim Neusesser · 6 min

Related Articles:

Should You Run a Survey?

Maddie Brown · 6 min

10 Survey Challenges and How to Avoid Them

Tanner Kohler · 15 min

Screening Participants for User-Research Studies

Maddie Brown · 7 min

User-Feedback Requests: 5 Guidelines

Anna Kaley · 10 min

Rating Scales in UX Research: Likert or Semantic Differential?

Maria Rosala · 7 min

Testing Visual Design: A Comprehensive Guide

Megan Chan · 10 min

How to write survey questions for research – with examples

- Post author: Marta Costa

- Post published: April 5, 2023

- Post category: Data Collection & Data Quality

- Last Updated: November 13, 2024

A good survey can make or break your research. Learn how to write strong survey questions, learn what not to do, and see a range of practical examples.

The accuracy and relevance of the data you collect depend largely on the quality of your survey questions . In other words, good questions make for good research outcomes. It makes sense then, that you should put considerable thought and planning into writing your research survey or questionnaire.

In this article, we’ll go through what a good survey question looks like, talk about the different kinds of survey questions that exist, give you some tips for writing a strong survey question, and finally, we’ll take a look at some examples.

What is a good survey question?

A good survey question should contain simple and clear language. It should elicit responses that are accurate and that help you learn more about your target audience and their experiences. It should also fit in with the overall design of your survey project and connect with your research objective. There are many different types of survey questions. Let’s take a look at some of them now.

New to survey data collection? Explore SurveyCTO for free with a 15-day trial.

Types of survey questions

Different types of questions are used for different purposes. Often questionnaires or surveys will combine several types of questions. The types you choose will depend on the overall design of your survey and your aims. Here is a list of the most popular kinds of survey questions:

These questions can’t be answered with a simple yes or no. They require the respondent to use more descriptive language to share their thoughts and answer the question. These types of questions result in qualitative data.

Closed-ended

A closed-ended question is the opposite of an open-ended question. Here the respondent’s answers are normally restricted to a yes or no, true or false, or multiple-choice answer. This results in quantitative data.

Dichotomous

This is a type of closed-ended question. The defining characteristic of these questions is that they have two opposing fields. For example, a question that can only be answered with a yes/no answer is a dichotomous question.

Multiple choice

These are another type of closed-ended question. Here you give the respondent several possible ways, or options, in which they can respond. It’s also common to have an “other” section with a text box where the respondent can provide an unlisted answer.

Rating scale

This is again another type of close-ended question. Here you would normally present two extremes and the respondent has to choose between these extremes or an option placed along the scale.

Likert scale

A Likert scale is a form of a rating scale. These are generally used to measure attitudes towards something by asking the respondent to agree or disagree with a statement. They are commonly used to measure satisfaction.

Ranking scale

Here the respondents are given a few options and they need to order these different options in terms of importance, relevance, or according to the instructions.

Demographic questions

These are often personal questions that allow you to better understand your respondents and their backgrounds. They normally cover questions related to age, race, marital status, education level, etc.

Ready to start creating your surveys? Sign up for a free 15-day trial.

7 Tips for writing a good survey question

The following 7 tips will help you to write a good survey question:

1. Use clear, simple language

Your survey questions must be easy to understand. When they’re straight to the point, it’s more likely that your respondent will understand what you are asking of them and be able to respond accurately, giving you the data you need.

2. Keep your questions (and answers) concise

When sentences or questions are convoluted or confusing, respondents might misunderstand the question. If your questions are too long, they may also get bored by the questions. And in your lists of answers for multiple choice questions, make sure your choice lists are concise as well. If your questions are too long, or if you’ve provided too many options, you may receive responses that are inaccurate or that are not a true representation of how the respondent feels. To limit the number of options a respondent sees, you can use a survey platform like SurveyCTO to filter choice lists and make it easy for respondents to answer quickly. If you have an exceptionally long list of possible responses, like countries, implement search functionality in your list of choices so your respondents can quickly search for their selection.

3. Don’t add bias to your question

You should avoid leading your respondent in any particular direction with your questions, you want their response to be 100% their thoughts without being unduly influenced. An example of a question that could lead the respondent in a particular direction would be: How happy are you to live in this amazing area? By adding the adjective amazing before area, you are putting the idea in the respondent’s head that the area is amazing. This could cloud their judgment and influence the way they answer the question. The word happy together with amazing may also be problematic. A better, less loaded way to ask this question might be something like this: How satisfied are you living in this area?

4. Ask one question at a time

Asking multiple things in one question is confusing and will lead to inaccuracies in the answer. When you write your question you should know exactly what you want to achieve. This will help you to avoid combining two questions in one. Here is an example of a double-barrelled question that would be difficult for a respondent to answer: Please answer yes or no to the following question: Do you drive to work and do you carry any passengers? In this question, the respondent is being asked two things, yet they only have the opportunity to respond to one. Even then, they don’t know which one they should respond to. Avoid this kind of questioning to get clearer, more accurate data.

5. Account for all possible answer choices

You should give your respondent the ability to answer a question accurately. For instance, if you are asking a demographic question you’ll need to provide options that accurately reflect their experience. Below, you can see there is an “other” option with space where the respondent can answer how they see fit, in the case that they don’t fit into any of the other options. Which gender do you most identify with:

- Prefer not to say

- Other [specify]

6. Plan the question flow and choose your questions carefully

Question writing goes hand-in-hand with questionnaire design. So, when writing survey questions, you should consider the survey as a whole. For example, if you write a close-ended question like: Were you satisfied with the customer service you received when you bought x product? You might want to follow it up with an open-ended question such as: Please explain the reason for your answer: This will help you draw out more information from your respondent that can help you assess the strengths and weaknesses of your customer service team. Making sure your questions flow in a logical order is also important.

For instance, if you ask a question regarding the total cost of a person’s childcare arrangements, but you’re unaware if they have children, you should first ask if they have children and how many. It’s also a good idea to start your survey with short, easy-to-answer, non-sensitive questions before moving on to something more complex. This way there is more chance you’ll engage your audience early on and make it more likely that they’ll continue with the survey. You should also consider whether you need qualitative or quantitative data for your research outcomes or a mix of the two. This will help you decide the balance of closed-ended and open-ended questions you use. With close-ended questions, you get quantitative data. This data will be fairly conclusive and simple to analyze. It can be useful when you need to measure specific variables or metrics like population sizes, education levels, literacy levels, etc.

On the other hand, qualitative data gained by open-ended questions can be full of insights. However, these questions can be more laborious for the respondent to complete making it more likely for them to skip through or give a token answer. They’re also more complex to analyze.

7. Test your surveys

Before a questionnaire goes anywhere near a respondent, it needs to be checked over. Mistakes in your survey questions can give inaccurate results. They can also waste time and resources. Having an impartial person check your questions can also help prevent bias. So, not only should you check your work, but you should also share it with colleagues for them to check. After checking your survey questions, make sure to check the functionality and flow of your survey. If you’re building your form in SurveyCTO, you can use our form testing interface to catch errors, make quick fixes, and test your workflows with real data.

Examples of good survey questions

Now that we’ve gone through some dos and don’ts for writing survey questions, we can move on to more practical examples of how a good survey question should look. To keep these specific to the research world we’ll look at three categories of questions.

- Household survey questions

- Monitoring and evaluation survey questions

- Impact evaluation survey questions

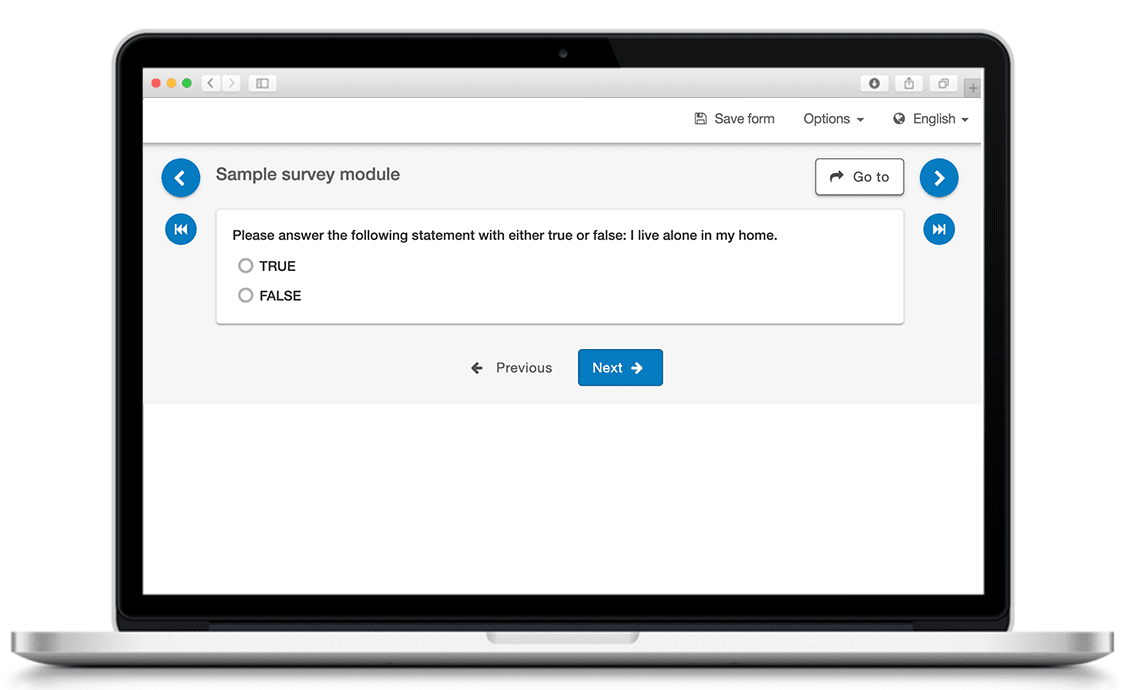

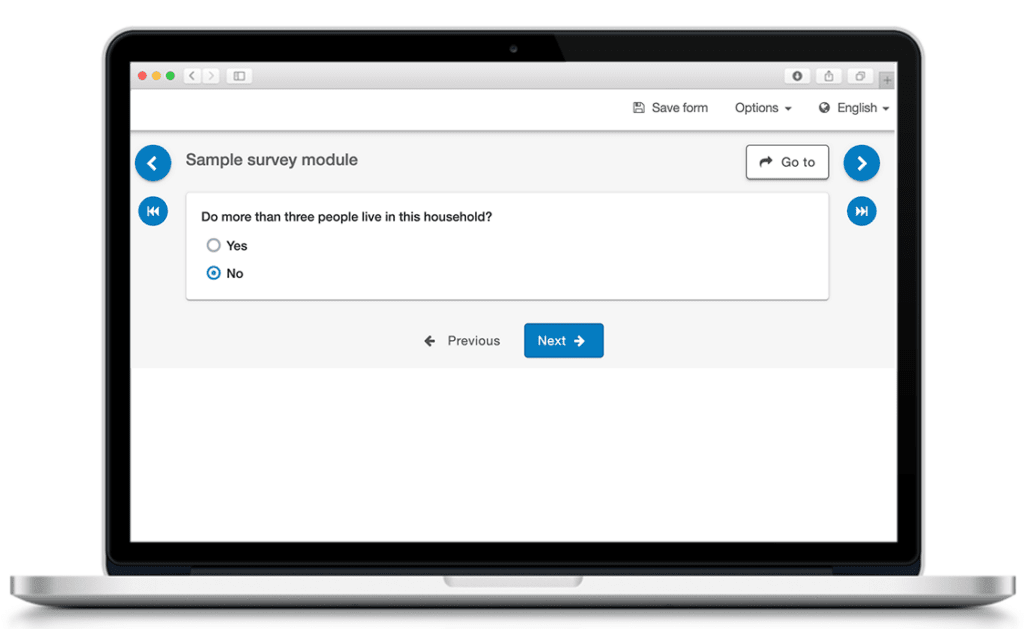

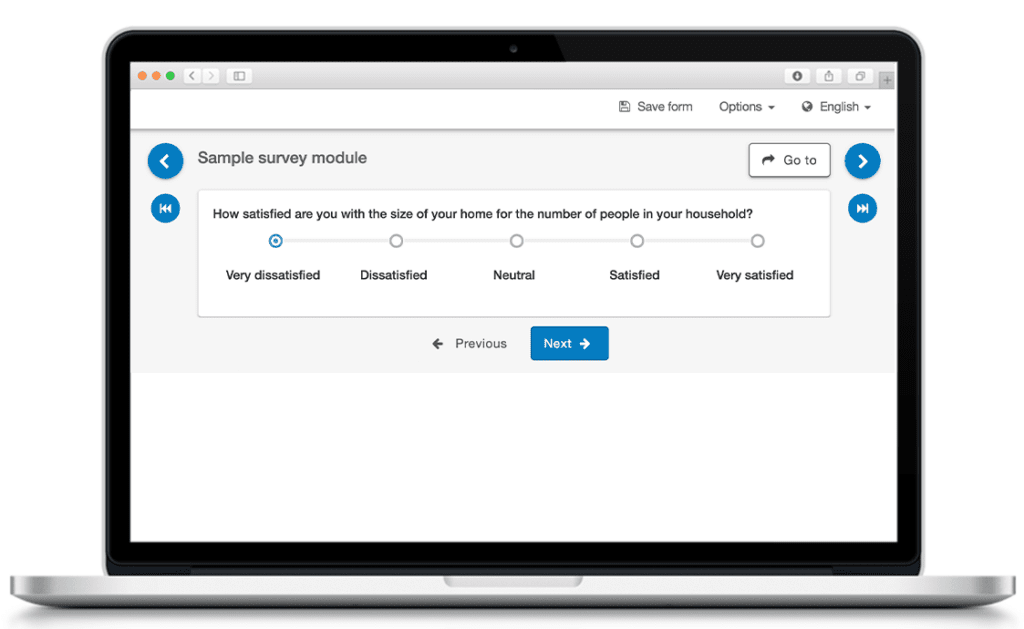

1. Household Survey Questions

2. monitoring and evaluation survey questions , 3. impact evaluation questions .

Strong survey questions lead to better research outcomes

Writing good survey questions is essential if you want to achieve your research aims. A good survey question should be clear, concise, and contain simple language. They should be free of bias and not lead the respondent in any direction. Your survey questions need to complement each other, engage your audience and connect back to the overall objectives of your research. Creating survey questions and survey designs is a large part of your research, however, is just a part of the puzzle. When your questions are ready, you’ll need to conduct your survey and then find a way to manage your data and workflow. Take a look at this post to see more ways SurveyCTO can help you beyond writing your research survey questions.

Your next steps: Explore more resources

To keep reading about how SurveyCTO can help you design better surveys, take a look at these resources:

- Sign up here to get notified about our monthly webinars, where organizations like IDinsight share best practices for effective surveys.

- Check out previous webinars from SurveyCTO about survey forms, like this one on high-frequency checks for monitoring surveys.

- Sign up for a free trial of SurveyCTO for your next survey project.

To see how SurveyCTO can help you with your survey needs, start a free 15-day trial today. No credit card required.

Marta Costa

Senior Product Specialist

Marta is a member of the Customer Success team for Dobility. She helps users working at NGOs, nonprofits, survey firms, universities and research institutes achieve their objectives using SurveyCTO, and works on new ways to help users get the most out of the platform.

Marta has worked in international development consultancy and research, supporting and coordinating impact evaluations, monitoring and evaluation projects, and data collection processes at the national level in areas such as education, energy access, and financial inclusion.

You Might Also Like

New SurveyCTO Collect call management features for phone surveys

SurveyCTO Desktop: Create your own workspace

SurveyCTO 2.60: New look meets smarter functionality

IMAGES

COMMENTS

This question doesn't include other options, such as healthiness of the food, price/value or some "other" reason. Over 10% of respondents would probably have a problem answering this question. Survey question mistake #6: Not using unbalanced scales carefully. Unbalanced scales may be appropriate for some situations and promote bias in others.