- News & Politics

- Science & Health

- Life Stories

- The New Sober Boom

- Getting Hooked on Quitting

- Liberal Arts Cuts Are Dangerous

- Is College Necessary?

- Dying Parents Costing Millennials Dear

- Gen Z Investing In Le Creuset

- Bitcoin Gambling

- Bitcoin Casinos

- Bitcoin Sports Betting

- Best Crypto Casinos in Canada

- Best Crypto Gambling in Canada

- SEC vs Celebrity Crypto Promoters

- 'Dark' Personalities Drawn to BTC

Did Nazis really try to make zombies? The real history behind one of our weirdest WWII obsessions

From comics to video games to indiana jones, the occult pursuits of nazi villains continue to fascinate us, by noah charney.

From the pages of "Hellboy" and the pixilated corridors of "Wolfenstein 3D," popular culture has wondered whether the Nazis, who had no shortage of well-documented kooky ideas, might have researched the possibility of reanimating the dead. Nazi zombies make for a grabber of a headline, but what real evidence is there that raising the dead was on the agenda for even the most outrageous among the Nazis?

We can begin with the conclusion, because that is really just the start. No reliable evidence has been found that the Nazis tried to raise the dead. But though even asking the question may sound preposterous, a world of people believe that such a program was in the works — and knowing what facts we do about Nazi research and beliefs, this concept is entirely plausible.

The idea that the Nazis looked into the possibility of raising the dead might sound like an outtake from an Indiana Jones movie. But this is only because those plots were inspired by real, but little-known, facts. The Nazis did, in fact, have teams of researchers hunting for supernatural treasures, religious relics and entrances to a magical land of telepathic faeries and giants (I wish I were making this up). Relatively few people are aware of a very real organization that was the inspiration for the Indiana Jones plots: the Nazi Ahnenerbe, or the Ancestral Heritage Research and Teaching Organization. (I wrote about the Ahnenerbe in my book " Stealing the Mystic Lamb: the True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Masterpiece.")

The Ahnenerbe (which literally means “Inheritance of the Forefathers”) was a research group into the paranormal, established by order of SS head Heinrich Himmler on 1 July 1935. It was expanded during the Second World War on direct orders from Adolf Hitler. Hitler’s interest in the occult, and the interest of many of the Nazi leaders (Himmler foremost among them) is well-documented. The Nazi Party actually began as an occult fraternity, before it morphed into a political party. Himmler’s SS, ostensibly Hitler’s bodyguard but in practice the leading special forces of the Nazi Army, was conceived of and designed based on occult beliefs. Wewelsburg, the castle headquarters of the SS, was the site of initiation rituals for SS “knights” that were modeled on Arthurian legend. The magical powers of runes were invoked, and the Ahnenerbe logo sports rune-style lettering. Psychics and astrologers were employed to attack the enemy and plan tactics based on the alignment of the stars. Nazis tried to create super-soldiers, using steroids and drug cocktails, in a twisted interpretation of Nietzsche’s übermensch.

What really got the Indiana Jones plots flowing were real Nazi expeditions launched through the Ahnenerbe. To Tibet, to search for traces of the original, uncorrupted Aryan race, and for a creature called the Yeti, what we would call the Abominable Snowman. To Ethiopia, in search of the Ark of the Covenant. To steal the Spear of Destiny from its display among the Crown Jewels of the Holy Roman Emperor at the Belvedere Palace in Vienna, the lance which Longinus used to pierce Christ’s side as Christ hung on the cross, and which would disappear from a locked vault in Nurnberg at the end of the war. To the Languedoc, to find the Holy Grail. Indiana Jones’ nemesis, the Nazi archaeologist Belloq, may have been inspired by Otto Rahn, a member of the Ahnenerbe who spent years in search of the Holy Grail and who penned several fascinating books on the Cathars, Templars and a cult built around Lucifer, who was a god of light appropriated by early Christians and equated with the Devil (Dan Brown, I hope you’re taking notes). It is certainly possible that Hitler believed that The Ghent Altarpiece contained a coded map to supernatural treasure, as some have posited. The Ahnenerbe was hard at work looking for a secret code in the Icelandic saga "The Eddas," which many Nazi officials thought would reveal the entrance to the magical land of Thule, a sort of Middle Earth full of telepathic giants and faeries, which they believed to be the very real place of origin of the Aryans. If they could find this entrance, then the Nazis might accelerate their Aryan breeding program, and recover the supernatural powers of flight, telepathy and telekinesis that they believed their ancestors in Thule possessed, and which was lost due to interbreeding with “lesser” races.

As kooky as all this may sound (and it sounds extremely kooky), such things were fervently believed by some powerful people in the Nazi Party — so much so that huge sums of money were invested into research, along with hundreds of workers and scientists. Michael Kater, a professor who publishes extensively on Nazi Germany and who penned a book on the Ahnenerbe, underscores that the occult obsession was limited primarily to a few individuals, albeit individuals with a great deal of power. “Apart from Himmler and the Ahnenerbe, there is not a shred of evidence that ‘intellectuals’ or culture brokers of the Third Reich would have been concerned with this question (of the dead, the zombies, or the occult, for that matter).” But because of the interest from Hitler and Himmler, above all — and, frankly, the weirdness of some of their beliefs and practices — popular culture has latched onto this almost two-dimensional mad villainy and assigned it to Nazis in general. Which brings us to zombies.

The pseudo-scientific institute of the Ahnenerbe, acting out Himmler’s fantasies and theories, both sought supernatural advantages for the Nazi war effort, but also had a propagandistic agenda, to seek “scientific” evidence to support Nazi beliefs, like Aryan racial superiority. These experiments on human subjects, many concentration camp inmates, provide a horrifying constellation of facts that can lead to the theory about Nazi experiments to reanimate the dead. This popular myth, embraced in video games and comic books, is actually a plausible conclusion when one considers a thicket of facts that weave around it. Let us examine the facts that are established, and see how they lead to the “Nazi zombies” theory — which, whether true or not, tells us interesting things about the way we think about the Nazis today.

On 28 April 1945, at a munitions factory depot called Bernterode, in the German region of Thuringia, 40,000 tons of ammunition were found. Inside the mine, investigating American officers noticed what looked like a brick wall, painted over to match the color of the mineshaft. The wall turned out to be 5 feet thick, the mortar between the bricks not yet fully hardened. Breaking through with pickaxes and hammers, the officers uncovered several vaults containing a wealth of Nazi regalia, including a long hall hung with Nazi banners and filled with uniforms, as well as hundreds of stolen artworks: tapestries, books, paintings, decorative arts, most of it looted from the nearby Hohenzollern Museum. In a separate chamber, they came upon a ghoulish spectacle: four monumental coffins, containing the skeletons of the 17 th century Prussian king, Frederick the Great, Field Marshall von Hindenburg, and his wife. The Nazis had seized human relics of deceased Teutonic warlords. The fourth coffin was empty, but bore an engraved plate with the name of its intended occupant: Adolf Hitler. The return of these corpses to their proper resting places was a military operation called “Operation Bodysnatch,” as termed by "Monuments Man" Captain Everett P. Lesley, Jr.

It was never clear what the Nazis planned to use these disinterred bodies for, but conspiracy theorists offered no shortage of suggestions. In 1950, a Life magazine writer speculated that “the corpses were to be concealed until some future movement when their reappearance could be timed by resurgent Nazis to fire another German generation to rise and conquer again.” This article’s specific wording, “rise and conquer again,” which was read by hundreds of thousands when it first came out, could be interpreted either metaphorically or literally — and this is perhaps where the idea that the Nazis hid the bodies in hopes of resurrecting their fallen warlords came to be. Add this to the gruesome experiments in which some Ahnenerbe researchers were engaged, and this “Nazi zombie” theory gets easier to understand.

Wolfram Sievers, director of Ahnenerbe and, in 1943, the Institute for Military Scientific Research Interrogation at Nuremberg, oversaw a particularly horrific program of medical testing on concentration camp inmates, some of which ran parallel to the concept of raising the dead.

There were three main categories of unethical medical experiments carried out by Nazi scientists, most of which were done under the supervision of Sievers and the Ahnenerbe (as well as, famously, by Josef Mengele at Auschwitz). Prisoners were used as some laboratories might experiment on animals.

The first category was survival testing. The idea was to determine the human survival thresholds for Nazi soldiers. One example was an experiment to determine the altitude at which air force crews could safely parachute. Prisoners were placed in low-pressure chambers to replicate the thin atmosphere of flight, and observed to see when organs began to fail. Sievers’ most infamous experiments at Dachau were to determine the temperature at which the human body would fail, in the case of hypothermia, and also how best to resuscitate a nearly-frozen human. A body temperature probe was inserted into the rectum of prisoners, who were then frozen in a variety of manners (for example, immersion in ice water or standing naked in the snow). It was established that consciousness was lost, followed quickly by death, when body temperature reached 25 C. Bodies of the nearly-frozen were then brought back up in temperature through a variety of similarly unpleasant manners, such as immersion in near-boiling water. Himmler himself suggested the most bizarre, but least cruel, method of reviving a hypothermic — by obliging him to have sex in a warm bed with multiple ladies. This was actually practiced (and seemed to work, at least better than the other methods). But the very idea that experiments were undertaken to kill or almost kill, humans through freezing, and then determine how best to resuscitate them, bring them back to life, is not a long leap to the reanimation of the clinically dead.

The second category of tests included those with pharmaceuticals and experimental surgeries, with inmates used like lab rats. Doctors tested immunizations against contagious diseases like malaria, typhus, hepatitis and tuberculosis, injecting prisoners and exposing them to diseases, then observing what happened. Procedural experiments, like those involving bone-grafting without anesthetic, which took place at the Ravensbrueck concentration camp, could also fall into this category. Antidotes were sought to chemical weapons like mustard gas and phosgene, with no regard for the well-being of those experimented upon. Keeping in mind the Nazi policy of using prisoners of “lesser” races for economic benefit (this is why concentration camp victims were often kept just alive enough to provide free labor, rather than universally being killed upon capture), this prisoner-as-guinea-pig approach fits into this perverse logic.

November 1944 saw an experiment with a cocktail drug called D-IX, at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. D-IX included cocaine and a stimulant called pervitine. The Luftwaffe (Nazi air force) had been supplied with 29 million pervitine pills from April-December 1939 alone, with the pill codenamed “obm.” Its use left the soldiers addicted, but did succeed in extending attention spans, reducing the need for sleep and food and giving a dramatic increase in stamina. 18 prisoners were given D-IX pills and forced to march while wearing backpacks loaded with 20 kilos of material — after taking the pills, they were able to march, without rest, up to 90 kilometers a day. The goal was to determine the outer limit of stamina induced by the pills. The D-IX pill proper, launched March 16th, 1944, included in each pill 5 mg of cocaine, 3 mg of pervitine, 5 mg of eucodal (a morphine-based painkiller) and synthetic cocaine. It was tested in the field with the Forelle diversionary unit of submariners. The experimentation and use of the pills, both on prisoners and soldiers, was considered very successful, and a plan was put in place to supply pills to the whole Nazi army, but the Allied victory months later stopped this. These pills sought to create super soldiers, in a contorted interpretation of the Nietzschean übermensch.

The third category was racial, or ideological testing, famously overseen by Josef Mengele, who experimented on twins and gypsies, to see how different races responded to contagious diseases. Mass-sterilization experiments on Jews and gypsies provided a sort of photo-negative to one of Himmler’s pet projects, called Lebensborn. It was a breeding program in which racially-ideal Aryan men and women (tall, blond-haired, blue-eyed, strong Nordic bone structure) were obliged to breed, in order to produce more, and purer, Aryan children. This was part and parcel with the belief that the Aryans of the 20 th century were descended from an ancient race with superhuman powers — and that these powers had been gradually lost through interbreeding with “lower” races. If the “pollution” of these other races could be bred out, through generations of Aryans mixing only with other Aryans, then perhaps these powers could be regained? This, too, has an echo of resurrection to it. Resurrecting the lost purity of the original Aryans from Thule, and bringing back their superhuman powers, through breeding programs with pure-blooded Aryans.

With all this in mind, but with the acknowledgment that no extant document attests to such a “Nazi zombie” program, we come to what may be the more interesting question. We think of the Nazis as crazy, cartoonishly-evil super villains. And many were. The facts attest that they were capable of lunatic theories and illogic. They are confirmed to have believed things no less fanciful than reanimating the dead. But what does this tell us about how we consider them today?

There is two-part danger to our tendency to lump “the Nazis” into a collective, super-evil entity. By dismissing a complex, layered political party, which featured millions of people who, personally, ran a nuanced gamut from good to evil, under the banner of “the Nazis,” we tend to pass over the behavior of individuals within that umbrella term. Each person under the auspices of Nazi Germany was three-dimensional, even the comic book super-villains like Himmler and Sievers. People made decisions within the context of the political atmosphere, acting better or worse than was expected or commanded of them. There were nurses who took it upon themselves to euthanize unwanted wounded, not because they were ordered to do so, but because they felt it was “right.” There were Germans who refused to follow orders, or who helped victims escape. The cauldron of the Second World War provoked bestial behavior in individuals, not just in big-name villains, and prompted acts of good amidst the turmoil. To lump so many millions of three-dimensional humans together under the banner of Nazi Germany both excuses the evil behavior and dismisses the good. It also risks dismissing the slow-build of Nazi power with a flick of the wrist: as if it was born of a cartoonish madness that could not happen again (whereas North Korea or ISIS, for example, seem to be incubators of similar behavior).

Michael Kater concurs: “When you think of it, there is also a self-exculpatory element here. If you can blame Nazi zombies for all the evil, you can take blame away from the Nazi humans. Hegel never said that zombies were responsible for evil humans' actions.” The sort of man-monsters who could concoct the Holocaust could surely have tried to raise an army of undead, but this idea further pushes them away from the feeling that they were real people, and that their ideas and era could, if we are not careful, resurface.

Kater continues, “What interests me in all this is not why the Nazis were guided by secret forces hiding in Tibet or under the ground (of course they were not), but why people think they were. One can take what circumstantial evidence one has and tie all this to mass psychology and actual history, or such. I do not know how many times I have been asked about the Nazis and the occult during my career (ever since I published the Ahnenerbe book in 1974, and then some). If people cannot explain something in ordinary, human, terms, they come up with conspiracy theories. Creationists need religion.” The Nazis seem so evil to us, that we tend to make of them a cartoon construct, emphasizing the real (though less-widespread than is generally imagined) influence of supernatural beliefs. Kater draws a parallel to the theories that rise up in other horrifying historical events. “One such instance was after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. These are incidents so gross that something super-natural must be behind them. However, it is really true: history writes the best, or the most gruesome, novels; makes the best films.”

At the end of the day, we can say without doubt that certain influential Nazis very much believed in the occult, and founded a research institute, the Ahnenerbe, to look into it. They engaged in experiments as bizarre and gruesome as trying to raise the dead, and they may well have toyed with that idea as well, although documentary evidence of it has not survived. But our mental construct of the Nazis, and the way popular culture assigns to them a two-dimensional, comic book type of evil, is as interesting, if not more so, than the question of whether they sought to raise a zombie army or animate their long-dead Teutonic warlords.

Noah Charney is a Salon arts columnist and professor specializing in art crime, and author of "The Art of Forgery" (Phaidon).

Related Topics ------------------------------------------

Related articles.

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

Real Life Zombies: Fact or Fiction?

Movies may get some things right for a zombie apocalypse. learn what science knows about real-life zombies and viruses, and if an apocalypse could happen - or not..

Several years back, a woman checked herself into a hospital psychiatric unit.

She needed help, she told her doctors , because she was terrified of… zombies.

Her doctors did what good doctors do: They used cognitive behavior therapy to help the woman question her thoughts and fears. Within days, the woman was laughing at her folly, and she was discharged.

It’s possible that zombies do lurch about our world — just not in the ways depicted in popular movies or television shows.

Real Life Zombie or Buried Alive?

For example, in the late 1990s, Roland Littlewood and Chavannes Douyon, of the University College of London, traveled to southern Haiti to study a woman who had reportedly been zombified.

Researchers referred to the woman as “FI,” who had died after suffering a fever.

Three years later, however, a friend spotted FI, seemingly alive, stumbling and swaying around the village. When FI’s parents dug up her grave, they found no body. Instead, the tomb was full of rocks. Cue the haunting music.

FI’s family and villagers referred to her as a zombie, but she hadn’t been bitten or infected with a virus. Rather, the researchers theorized, someone had drugged FI with a neuromuscular toxin that paralyzed her, making her appear to be dead.

After she was buried alive, she’d run out of oxygen and suffered brain damage, the researchers mused. Her assailant then dug her free and potentially administered datura stramonium (also known as jimsonweed ).

“The use of Datura stramonium […] and its possible repeated administration during the period of zombie slavery could produce a state of extreme psychological passivity,” writes the researchers in the Lancet .

Here’s the thing: It’s not super clear if the above is truly what happened to FI — or any other so-called zombified person. “Mistaken identification of a wandering, mentally ill stranger by bereaved relatives is the most likely explanation,” writes the two researchers.

On top of that, poison isn’t contagious, which means FI and others like her are not about to trigger a zombie apocalypse.

Is the Zombie Virus Real?

That’s often what happens in the movies, right? A flu virus mutates, spreads and infects people, transforming them into undead, off-balance brain eaters. Could that happen?

Not really. To understand why, let’s look at a modern-day virus that comes closest to zombifying its prey: Rabies.

Like in the movies, rabies spreads through bites and scratches, and it also eats away at the brain. When the cerebellum goes offline, rabies victims stumble around in an agitated, zombie-like state.

However, rabies sufferers are not undead — nor do they crave brains. More importantly, modern medicine can prevent the disease.

“It would be hard to imagine a pandemic that spreads by people biting each other,” explains Steven Schlozman, associate professor of psychiatry, pediatrics and medical education at Dartmouth. “Zombies are not that fast or coordinated. We could get ahead of that. We could put a fence around them, study them, and figure out what’s wrong with them.”

That said, zombie movies aren’t complete works of fiction.

Read More: 'Zombie' Viruses, Up to 50,000 Years Old, Are Awakening

Can a Zombie Apocalypse Happen Like the Movies?

They do get some things right, says Schlozman, whose 2011 novel, The Zombie Autopsies , was optioned by George Romero, the creator of the Night of the Living Dead series of zombie films.

“The crossovers have less to do with what turns someone into a zombie, and more to do with our response to them,” says Schlozman.

Though the film version of The Zombie Autopsies was never made, the opening scene would have depicted humans getting in a fistfight on an airplane as they argued over whether they should or shouldn’t be forced to wear masks.

“George said that, if this happened, people would argue about it,” says Schlozman. “That was back in 2013. Sadly, now we know he was right.”

Read More: Five Apocalypses Humanity Has Survived

Zombie Pandemic Parallels

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, a parent made news for punching a teacher over masking rules. After a Missouri school board approved a masking mandate , a fistfight broke out.

Here’s another common social thread. In zombie movies and television shows, human cooperation often breaks down. Rather than working together to solve problems, healthy humans tend to gather in small tribes, often raiding and warring with other tribes over resources and power.

“In the movies, we always see these petty arguments about race or class,” says Schlozman.

Similarly, during COVID-19, protesters plastered flyers with the words “Jew” and “fraud” in Hawaii Lt. Gov. Josh Green’s neighborhood. Racism against Asian Americans jumped more than 300 percent.

“One of the things these movies show is when we see something that doesn't add up to us, we end up marshaling those brain regions that are most consistent with the zombies,” says Schlozman. “George was a little melancholy about humanity. He was like, ‘We could handle this. The saddest thing about my movies,’ he always said, ‘is that it doesn’t have to be this way.’”

Read More: Here's What Really Inspired Vampire Legends

- microbes & viruses

- behavior & society

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

The Curious World of Zombie Science

Zombies seem to be only growing in popularity, and I’m not talking about the biological kind

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

Sarah Zielinski

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/zombie-science.jpg)

Zombies seem to be only growing in popularity, and I'm not talking about the biological kind . They've got their own television show , plenty of films , and even a musical . They invaded the world of Jane Austen, and there are zombie crawls around the world, in which people dress up like the living dead and shuffle across some urban area.

And then there's the growing field of zombie science.

In 2009, University of Ottawa mathematician Robert J. Smith? (and, yes, he really does include a question mark at the end of his name) published a paper in a book about infectious disease modeling titled "When Zombies Attack! Mathematical Modelling of an Outbreak of Zombie Infection" ( pdf ). It started as a class project, when some students suggested they model zombies in his disease modeling class. "I think they thought I'd shoot it down," Smith told NPR , "but actually I said, go for it. That sounds really great. And it was just a fun way of really illustrating some of the process that you might have in modeling an infectious disease." Using math, the group showed that only by quickly and aggressively attacking the zombie population could normal humans hope to prevent the complete collapse of society.

That paper sparked further research. The latest contribution, "Zombies in the City: a NetLogo Model" ( pdf ) will appear in the upcoming book Mathematical Modelling of Zombies . In this new study, an epidemiologist and a mathematician at Australian National University refine the initial model and incorporate the higher speed of humans and our capacity to increase our skills through experience. They conclude that only when human skill levels are very low do the zombies have a chance of winning, while only high human skill levels ensure a human victory. "For the in-between state of moderate skill a substantial proportion of humans tend to survive, albeit in packs that are being forever chased by zombies," they write.

Then there's the question of whether math is really the most important discipline for surviving a zombie attack.

But how might zombies come about? There are some interesting theories, such as one based on arsenic from Deborah Blum at Speakeasy Science . Or these five scientific reasons a zombie apocalypse could happen, including brain parasites, neurotoxins and nanobots.

A Harvard psychiatrist, Steven Schlozman, broke into the field of zombie research and then wrote The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse , which blames an airborne contagion for the zombie phenomenon. The book delves into the (fictional) research of Stanley Blum, zombie expert, who searched for a cure to the zombie epidemic with a team of researchers on a remote island. (They were unsuccessful and succumbed to the plague, but nicely left their research notes behind, complete with drawings.) It's more than just fun fiction to Schlozman, though, who uses zombies to teach neuroscience. "If it works right, it makes students less risk-adverse, more willing to raise their hands and shout out ideas, because they’re talking about fictional characters," he told Medscape .

For those interested in getting an overview of the science, a (spoof) lecture on the subject, Zombie Science 1Z , can now be seen at several British science and fringe festivals. Zombiologist Doctor Austin, ZITS MSz BSz DPep, lectures in three modules: the zombieism condition, the cause of zombieism, and the prevention and curing of zombieism. And for those of us who can't attend in person, there's a textbook and online exam.

And the Zombie Research Society keeps track of all this and more, and also promotes zombie scholarship and zombie awareness month. Their slogan: "What you don't know can eat you."

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

Sarah Zielinski | | READ MORE

Sarah Zielinski is an award-winning science writer and editor. She is a contributing writer in science for Smithsonian.com and blogs at Wild Things, which appears on Science News.

September 20, 2019

Real-Life Zombies

A zombie takeover is science fiction, right? Well, it turns out some zombies already exist in nature and “life” after brain death might not be so far-fetched

By Everyday Einstein Sabrina Stierwalt

Marc Mateos Getty Images

Maybe the zombie apocalypse starts with a virus or a supernatural event. Maybe the resulting zombies can move quickly but are more easily incapacitated, or maybe they’re slow and can be only taken out by a blow to the brain. Are these zombies cunning? Or are they awkward and uncoordinated, as I would argue any proper zombie must be?

Zombie lore may give us a lot of variety, but one thing every zombie scenario has in common is reanimation of the body after death. The body’s movements are slave to a brain that is no longer in control. But what do these differences matter? It’s all just science fictional horror movie fodder, right? Well, we’ve previously discussed scientific studies on how fast a zombie-like virus could spread , as well as neurobehavioral disorders in humans that leave their sufferers mimicking some key zombie traits. And it turns out, science has even more to say about zombies.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Zombie Carpenter Ants

In the Brazilian jungle, at a height of just about 10 inches off the ground, carpenter ants can be found with their jaws permanently locked on a leaf, frozen in a never-ending dance as an alien stalk grows through their head. These ants are the victims of ophiocordyceps unilateralis , also known as the zombie ant fungus.

The fungus first enters an ant’s bloodstream as single cells, but those cells soon begin copying themselves and, importantly, building connections so that those individual cells can share nutrients. These connections set the ophiocordyceps fungus apart from other fungi that simply kill off their host and eventually form networks that wrap around the ant’s muscles.

As the fungal network grows, the ant’s body succumbs to the fungus’s control. Interestingly, this network doesn’t appear to reach the ant’s brain. Entomologists are not sure whether the fungus releases chemicals that affect the ant’s brain from afar, effectively killing it as far as the ant is concerned, or if it takes a more sinister approach by leaving the ant’s brain alone to witness the remainder of the takeover but cutting off any muscle control, and thus the brain’s ability to stop it.

Either way, the ant is compelled to leave its colony and climb up a nearby plant to the precise height above the jungle floor where the humidity and temperature are optimal for the fungus to thrive. The ant is then forced to bite into a leaf to maintain its position, never to move again.

But the fungus isn’t done yet. With its host in perfect position, the fungal passenger forms a stalk that breaks through the ant’s head and produces spores that then rain down on the other ants below, grabbing more victims.

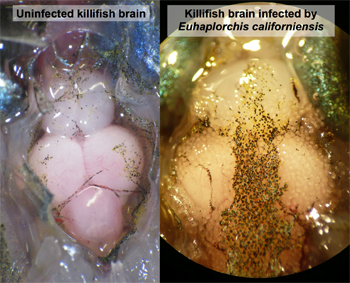

The zombie ant fungus isn’t alone in having the power to manipulate its host to best serve its own interest. For example, in an attempt to gain entry into host birds, a type of flatworm first invades the brains of California killifish causing them to exhibit “ conspicuous swimming behaviors ” that make them more vulnerable to attacks by those birds. But it does show a so far uniquely known ability to adapt over different climates .

As I mentioned, the Brazilian flavor of the fungus directs its host ants to hover around 25 centimeters off the jungle floor by biting onto a leaf. The whole stalk and spore creation process that spreads the fungus to other ants takes one to two months. However, in cooler climates like Japan and South Carolina, the ants are found instead clinging to twigs in trees several feet off the ground. In these climates the spreading of spores takes over a year and so the zombified ant must survive a winter season during which a leaf might fall to the ground but a twig will endure.

The scientists leading the study , including David Hughes and Raquel Gontijo de Loreto of Penn State, had a lot of help from a citizen scientist , Kim Fleming, who carefully documented the infestation of zombified ants that call her South Carolina property home. In a very unique claim to fame, the strain of fungus infecting her ants is now known as Ophiocordyceps kimflemingiae.

The change in climate that inspired this particular adaptation is expected to have happened in the distant past. But what does this mean for the rapidly changing climate we live in today? If the fungus is clever enough to alter its plans to accommodate the seasons, what adaptation will we see next?

»Continue reading “Real-Life Zombies” on QuickAndDirtyTips.com

It’s a wonderful world — and universe — out there.

Come explore with us!

Science News Explores

Zombies are real.

This is no Halloween make-believe story. Real zombies are out there — maybe in your own backyard!

It may be fun to dress up like a zombie for Halloween, but real zombies do exist. They’re just not human. They’re animals under the mind control of parasites.

treasuredragon/istockphoto

Share this:

- Google Classroom

By Kathryn Hulick

October 27, 2016 at 6:00 am

A zombie crawls through the forest. When it reaches a good spot, it freezes in place. A stalk slowly grows from its head. The stalk then spews out spores that spread, turning others into zombies.

This is no Halloween story about the zombie apocalypse. It’s all true. The zombie isn’t a human, though. It’s an ant. And the stalk that emerges from its head is a fungus. Its spores infect other ants, which lets the zombie cycle begin anew.

In order to grow and spread, this fungus must hijack an ant’s brain. However weird this might seem, it isn’t all that unusual. The natural world is full of zombies under mind control. Zombie spiders and cockroaches babysit developing wasp larvae — until the babies devour them. Zombie fish flip around and dart toward the surface of the water, seeming to beg for birds to eat them. Zombie crickets, beetles and praying mantises drown themselves in water. Zombie rats are drawn to the smell of the pee of cats that may devour them.

All of these “zombies” have one thing in common: parasites. A parasite lives inside or on another creature, known as its host. A parasite may be a fungus, a worm or another tiny creature. All parasites eventually weaken or sicken their hosts. Sometimes, the parasite kills or even eats its host. But death of the host isn’t the freakiest goal. A parasite might get its host to die in a certain place, or be eaten by a certain creature. In order to accomplish these tricks, some parasites have evolved the ability to hack into the host’s brain and influence its behavior in very specific ways.

How do parasites turn insects and other animals into the walking almost-dead? Every parasite has its own method, but the process usually involves altering chemicals within the victim’s brain. Researchers are working hard to identify which chemicals are involved and how they end up so bizarrely altering their host’s behavior.

Brains, brains! Ant brains!

A fungus doesn’t have a brain. And worms and single-celled critters obviously aren’t very smart. Yet somehow they still control the brains of larger, and smarter, animals.

“It blows my mind,” says Kelly Weinersmith. She is a biologist who studies parasites at Rice University in Houston, Texas. She is particularly interested in “zombie” creatures. True zombies, she points out, aren’t exactly like the type you find in horror stories. “In no way are these animals coming back from the dead,” she says. Most real zombies are doomed to die — and some have very little control over their actions.

The horsehair worm, for instance, needs to emerge in water. To make this happen, it forces its insect host to leap into a lake or swimming pool. Often, the host drowns.

Toxoplasma gondii (TOX-oh-PLAZ-ma GON-dee-eye) is a single-celled creature that can only complete its life cycle inside a cat. But first, this parasite must live for a time in a different animal, such as a rat. To ensure this part-time host gets eaten by a cat, the parasite turns rats into cat-loving zombies.

In Thailand, a species of fungus — Ophiocordyceps — can force an ant to climb almost exactly 20 centimeters (about 8 inches) up a plant, to face north and then to bite down on a leaf. And it makes the ant do this when the sun is at its highest point in the sky. This provides ideal conditions for the fungus to grow and release its spores.

Biologist Charissa de Bekker wants to better understand how that fungus exerts that mind control over the ants. So she and her team have been studying a species related to the Ophiocordyceps fungus in Thailand. This U.S. cousin is a fungus native to South Carolina. It, too, forces ants to leave their colonies and climb. These ants, though, bite down on twigs instead of leaves. This is likely due to the fact that trees and plants in this state lose their leaves in the winter.

De Bekker began these studies at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. There, her team infected a few species of ant with the South Carolina fungus. The parasite could kill all of the different ants she introduced to it. But the fungus made plant-climbing zombies only out of the species that it naturally infects in the wild.

To figure out what was going on, de Bekker’s team collected new, uninfected ants of each species. Then, the researchers removed the insects’ brains. “You use forceps and a microscope,” she says. “It’s sort of like that game Operation.”

The researchers kept the ant brains alive in small Petri dishes. When the fungus was exposed to its favorite brains (that is, ones from the ants that it naturally infects in the wild), it released thousands of chemicals. Many of these chemicals were completely new to science. The fungus also released chemicals when exposed to unfamiliar brains. These chemicals, however, were completely different. The researchers published their results in 2014.

The experiments at Penn State by de Bekker’s team were the first to create ant zombies in the lab. And the researchers only succeeded after setting up artificial 24-hour cycles of light and darkness for the zombies and their parasites.

It will take more work to learn how the parasite’s chemicals lead to zombie behavior in ants. “We are very much in the beginning of trying to figure this out,” says de Bekker. She now studies ant zombies at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, Germany. There, she is now probing how that daily cycle of sunlight and darkness affects zombification.

@sciencenewsofficial Nature is full of parasites that take over their victims’ minds and drive them toward self-destruction. #zombies #parasites #insects #science #learnitontiktok ♬ original sound – sciencenewsofficial

Soul-sucking wasps

Of all parasites, wasps know some of the creepiest tricks. One wasp, Reclinervellus nielseni , lays its eggs only on orb-weaving spiders. When a wasp larva hatches, it slowly sips its host’s blood. The spider stays alive long enough to spin a web. But not just any web. It spins a nursery of sorts for the wriggly, worm-like wasp baby stuck to its back.

The spider will even break down its old web to start a new one for the larva. “The [new] web is stronger than the normal web,” explains Keizo Takasuka. He studies insect behavior and ecology at Kobe University in Japan. When the web is done, the larva eats its spider host.

Now the larva spins a cocoon in the middle of the web. The extra strong threads most likely help the larva stay safe until it emerges from its cocoon 10 days later.

Story continues after video.

The jewel wasp puts an insect on the menu it serves up to its young: cockroach. But before a wasp larva can chow down, its mother needs to catch a bug that’s twice her size. To do this, says Frederic Libersat, “she transforms the cockroach into a zombie.” Libersat is a neurobiologist who studies how the brain controls behavior. He works at Ben Gurion University in Beer-Sheva, Israel.

The jewel wasp’s sting takes away a cockroach’s ability to move on its own. But it follows like a dog on a leash when the wasp pulls on its antenna. The wasp leads the cockroach to her nest and lays an egg on it. Then she leaves, sealing the egg inside the nest with its dinner. When the egg hatches, the larva slowly devours its host. Being a zombie, this cockroach never tries to fight back or escape.

This scenario is so creepy that biologists named a similar wasp Ampulex dementor — after a supernatural enemy in the Harry Potter series. In these books, dementors can devour people’s minds. This leaves the victim alive but without a self or soul. (Although A. dementor is a close relative of the jewel wasp, Libersat notes that researchers have not yet confirmed that it also turns cockroaches or any other insect into mindless slaves.)

Libersat’s group has focused its research on figuring out what the jewel wasp does to the cockroach mind. The mother jewel wasp performs something like brain surgery. She uses her stinger to feel around for the right part of her victim’s brain. Once found, she then injects a zombifying venom.

When Libersat removed the targeted parts of a roach’s brain, the wasp would feel around what was left of the roach’s brain with her stinger for 10 to 15 minutes. “If the brain was present, [the wasp] would take less than a minute,” he notes. This shows that the wasp can sense the right place to inject its poison.

That venom might interfere with a chemical in the roach’s brain called octopamine, Libersat reports. This chemical helps the cockroach stay alert, walk and perform other tasks. When researchers injected a substance similar to octopamine into zombie cockroaches, the insects again began walking.

Libersat cautions, however, that this is likely just one piece of the puzzle. There is still work to do to understand the chemical process happening in the cockroach’s brain, he says. But Weinersmith, who was not involved in the research, notes that Libersat’s team has worked out this chemical process in more detail than is available for most types of zombie mind control.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Brain worms

Weinersmith’s specialty is zombie fish. She studies California killifish infected with a worm called Euhaplorchis californiensis (YU-ha-PLOR-kis CAL-ih-for-nee-EN-sis). A single fish may have thousands of these worms living on the surface of its brain. The wormier the brain, the more likely the fish is to behave strangely.

“We call them zombie fish,” she says, but admits that they are less like zombies than the ants, spiders or cockroaches. An infected fish will still eat normally and stay in a group with its pals. But it also tends to dart toward the surface, twist its body around or rub against rocks. All of these actions make it easier for birds to see the fish. Indeed, it’s almost like the infected fish wants to get eaten.

And that’s precisely the point, says Weinersmith — for the worm. This parasite can only reproduce inside a bird. So it alters the fish’s behavior in a way that attracts birds. Infected fish are 10 to 30 times more likely to get eaten. That’s what Weinersmith’s colleagues Kevin Lafferty of the University of California, Santa Barbara and Kimo Morris of Santa Ana College in California discovered.

Weinersmith now is working with Øyvind Øverli at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, in As. They are studying the chemical processes behind the zombie fish’s bird-seeking behavior. So far, it seems that zombie fish may be less stressed out than their normal cousins. Researchers know what chemical changes should happen to a killifish brain when something, such as the sight of a bird on the prowl, stresses it out. But in a zombie fish’s brain, these chemical changes don’t seem to occur.

It’s as if the fish notices the hunting bird but doesn’t get freaked out as it should. “We need to do further studies to confirm this is true,” says Weinersmith. Her group plans to analyze the chemicals in the brains of infected fish, then try to recreate the zombie effect in normal fish.

Success won’t come easily. Zombie mind control is a complicated matter. Parasites have developed their control of other creatures’ brains over millions of years of evolution. Scientists have found fossil evidence of fungus-controlled ants dating back 48 million years. Over this long period, she says, “the fungus ‘learned’ a lot more about how the ant’s brain works than human scientists have.”

But scientists are starting to catch up. “Now we can ask [the parasites] what they’ve learned,” quips Weinersmith.

Ant brains may be much simpler than human brains, but the chemistry going on inside them isn’t all that different. Figuring out the secrets of zombie mind control in bugs could help neuroscientists understand more about the links between the brain and behavior in people.

Eventually, this work could lead to new medicines or therapies for human brains. We just have to hope that a mad scientist won’t go out and start making human zombies!

More Stories from Science News Explores on Health & Medicine

Science works to demystify hair and help it behave

Why you shouldn’t just brush off dandruff

Here’s why being creative is good for your brain

In 2024, bird flu posed big risks — and to far more than birds

Can furry pets get H5N1 bird flu and spread it to us?

The discovery of microRNA wins the 2024 Nobel Prize in physiology

More than 100 types of bacteria found living in microwave ovens

Zap, zap, zap! Our bodies are electric

🛍️ We hand-picked the best Cyber Monday deals . Don’t miss out. 🛍️

- svg]:fill-accent-900 [&>svg]:stroke-accent-900">

Could Scientists Really Create a Zombie Virus

By Ryan Bradley

Posted on Feb 25, 2011

Maybe, but it’s not going to be easy. In West African and Haitian vodou, zombies are humans without a soul, their bodies nothing more than shells controlled by powerful sorcerers. In the 1968 film Night of the Living Dead, an army of shambling, slow-witted, cannibalistic corpses reanimated by radiation attack a group of rural Pennsylvanians. We are looking for something a little in between Haiti and Hollywood: an infectious agent, a zombie virus if you will, that renders its victims half-dead but still-living shells of their former selves.

See our gallery of real live zombies in nature.

An effective agent would target, and shut down, specific parts of the brain , says Steven C. Schlozman, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard University and author of The Zombie Autopsies, a series of fictional excerpts from the notebooks of “the last scientist sent to the United Nations Sanctuary for the study of ANSD,” a zombie virus. Schlozman explained to PopSci that although the walking dead have some of their motor skills intact—walking, of course, but also the ripping and tearing necessary to devour human flesh—the frontal lobe, which is responsible for morality, planning, and inhibiting impulsive actions (like taking a bite out of someone), is nonexistent. The cerebellum, which controls coordination, is probably still there but not fully functional. This makes sense, since zombies in movies are usually easy to outrun or club with a baseball bat.

The most likely culprit for this partially deteriorated brain situation, according to Schlozman, is as simple as a protein. Specifically, a proteinaceous infectious particle, a prion. Not quite a virus, and not even a living thing, prions are nearly impossible to destroy, and there’s no known cure for the diseases they cause.

The first famous prion epidemic was discovered in the early 1950s in Papua New Guinea, when members of the Fore tribe were found to be afflicted with a strange tremble. Occasionally a diseased Fore would burst into uncontrollable laughter. The tribe called the sickness “kuru,” and by the early ’60s doctors had traced its source back to the tribe’s cannibalistic funeral practices, including brain-eating.

Prions gained notoriety in the 1990s as the infectious agents that brought us bovine spongiform encephalopathy, also known as mad cow disease. When a misshapen prion enters our system, as in mad cow, our mind develops holes like a sponge. Brain scans from those infected by prion-based diseases have been compared in appearance to a shotgun blast to the head.

Now, if we’re thinking like evil geniuses set on global destruction, the trick is going to be attaching a prion to a virus, because prion diseases are fairly easy to contain within a population. To make things truly apocalyptic, we need a virus that spreads quickly and will carry the prions to the frontal lobe and cerebellum. Targeting the infection to these areas is going to be difficult, but it’s essential for creating the shambling, dim-witted creature we expect.

Jay Fishman, director of transplant infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, proposes using a virus that causes encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain’s casing. Herpes would work, and so would West Nile, but attaching a prion to a virus is, Fishman adds, “a fairly unlikely” scenario. And then, after infection, we need to stop the prion takeover so that our zombies don’t go completely comatose, their minds rendered entirely useless. Schlozman suggests adding sodium bicarbonate to induce metabolic alkalosis, which raises the body’s pH and makes it difficult for proteins like prions to proliferate. With alkalosis, he says, “you’d have seizures, twitching, and just look awful like a zombie.”

Have a science question you’ve always wondered about? Email [email protected]

PopSci's Guide to Cyber Monday

The best Cyber Monday sales, deals, and everything else you need to know. Our team spends hundreds of collective hours searching and evaluating every deal we can find online, focusing on well-made and reviewed products for prices that make sense.

Diagnosis Zombie: The Science Behind the Undead Apocalypse

NEW YORK — When Harvard Medical School professor and psychiatrist Dr. Steven Schlozman sat down here at LiveScience's offices to talk about zombies, he wanted to get one thing out of the way.

"They're not real," Schlozman said. "They don't exist. I'm a practicing physician, and I'm required to tell you when you should be worried — you don't need to worry about zombies."

Schlozman has made a name for himself as "Dr. Zombie," an expert on the undead. He recently teamed up with actress Mayim Bialik, who plays a neuroscientist on "The Big Bang Theory" and actually holds a doctorate in neuroscience in real life, for a new program called STEM Behind Hollywood . (STEM stands for science, technology, engineering and math.)

The initiative aims to explain the real-world concepts behind movie plots — including zombie-movie plots — with classroom activities developed by calculator maker Texas Instruments and scientists who consult for Hollywood films.

We caught up with Schlozman on Wednesday (Aug. 7) and learned how to diagnose the undead, and how to track a real-life zombie apocalypse.

How Dr. Schlozman became Dr. Zombie

"My wife, in 2008, was diagnosed with breast cancer. She's totally fine now. But at the time, I couldn't sleep," Schlozman said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One night when he couldn't sleep, he turned to late-night TV and happened to catch " Night of the Living Dead ," considered the first true American zombie movie, made on a low budget in 1968 by George Romero.

"I started watching it, and I was thinking, 'They're sick. They're not just ghouls stumbling around in this graveyard … They're ill with something,'" Schlozman said.

He couldn't cure his wife's cancer, Schlozman thought, but maybe he could tackle the zombie problem. So he sat down and wrote a fake medical paper about zombies, which made the rounds on the Internet. Soon, he was getting speaking engagements. He eventually published a book, "The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse" (Grand Central Publishing, 2011), which is now being made into a movie, directed by none other than George Romero.

"The ones I like, the ones I find most scary and the most compelling, are the slow, shambling, dumb-as-a-doorknob zombies," Schlozman told LiveScience. "You could eat a sandwich while you're running away from them. They can't open windows, can't open doors, and they want to eat you."

But in his book, Schlozman departs from the traditional concept of zombies by creating characters who are only philosophically dead.

"The classic trope has them rising from the dead," Schlozman said. "Mine don't, because I wanted to make it as scientifically plausible as possible — knowing, of course, that it's not scientifically plausible at all."

As a physician, it's nearly impossible to watch movies about zombies without diagnosing their obvious neurological problems, Schlozman said. Even though the symptoms are fictional, they can be useful teaching tools for students. The "Zombie Apocalypse" activity on Texas Instruments' app walks students through the signs of worsening sickness, showing which parts of the brain would be affected.

"The first thing you would notice is a shuffling gait, difficulty walking well, difficulty with balance, difficulty with knowing where your body is in space," Schlozman said. Those problems would be rooted in the cerebellum, a region at the bottom of the brain responsible for motor skills and coordination, he said. [ Zombie Animals: 5 Real-Life Cases of Body-Snatching]

"You'd also notice they're not very bright," he added. "They don't seem to know what they're doing."

Those symptoms would indicate some damage or abnormality in the frontal lobe, which also controls impulsivity Schlozman said. "You've never seen a hesitant zombie," he noted.

The undead are not only dumb and impulsive, but also angry, which could be a sign of overexcited amygdalae , the pair of almond-shaped regions of gray matter deep inside the brain, Schlozman said.

But maybe zombies are angry because they simply can't get enough to eat. Their ravenous hunger, Schlozman noted, is maybe the most difficult symptom to explain from a clinical standpoint.

"The idea of being insatiably hungry and ill — that's a hard one to pull off, but you can do it," Schlozman said. "There are certain viruses and also certain lesions that can affect a region of the brain — the ventromedial hypothalamus — that affect satiety, and that affects the sense that you've eaten enough." Strains of human adenovirus , for example, have been linked to obesity.

How the zombie virus spreads

The symptoms of being a zombie don't add up to any recognizable disease, so it's not easy to find an exact parallel between the imagined zombie apocalypses of the movies and the outbreaks that epidemiologists dread in the real world. But the pattern of a pandemic can be represented quite neatly on a graph, whether it unfolds slowly or quickly, through splattered brains or airborne droplets.

"Any contagion that spreads has a certain mathematical way that it spreads," Schlozman said. With mathematical models, researchers can ask, "If there were a zombie bug, what would the spread look like if it were spread through biting?" he said.

Viruses transmitted through bites, such as the rabies virus, don't actually spread quickly because they can be isolated, Schlozman said. The spread of an airborne virus, such as influenza , meanwhile, could spread rapidly across a region, he added. That's the model he chose for "The Zombie Autopsies."

"All of the pandemics we've had on the Earth typically have been airborne," Schlozman explained. "So we had to have an airborne bug, but we know airborne bugs don't make you into zombies. So then we had to have an airborne bug that makes you hungry and an airborne bug that also degrades some of your higher brain function."

If there were ever a zombie takeover that looked like one in the movies, it would probably have to be set off by some sinister man-made pathogen.

Human lessons, too

Zombie movies would be much less exciting if they were just about the lumbering, flesh-eating corpses.

"That would be like a story about snails," Schlozman said. "They just would bump into each other, and it would be boring."

A good zombie movie with a happy ending tends to have humans overcoming their petty differences and banding together to quell the unstoppable tide of the undead. In the real world, those Hollywood-style dramas often play out on the international stage.

Schlozman pointed to the 2003 outbreak of SARS (short for severe acute respiratory syndrome), which sickened 8,000 people worldwide, and killed nearly 800.

"We would have gotten that genie back into the bottle sooner had the place where the virus originated — which was primarily China — been more willing to cooperate early on," he said.

But by the time a strain of the H1N1 flu virus caused a swine flu outbreak in 2009, international cooperation came together more smoothly. China was much more forthcoming with the World Health Organization, and epidemiologists were much better able to track the flu's spread, though it turned out to be less deadly than initially feared.

Why we love zombies

Zombie movies often reflect a culture's greatest fears. The thing that turns people into zombies is usually whatever we're most afraid of at the time, Schlozman said.

"When they [zombie movies] first started being made in the '60s, it was Cold War, radiation — and it's oozed its way toward pandemic, and in that pandemic mode, it took on an apocalyptic feel," he said.

Studies show that during times of economic stress, zombie movies become more popular, he said, because they represent what happens when the system is stressed and breaks down.

Schlozman said he also suspects that people's fascination with zombies partly stems from a longing to reconnect with one another.

"People ask, 'Why do we have these zombie walks? ... Why would you dress up like a dead person and walk around?'" he said. "Well, no one texts on a zombie walk. No one's looking at their phones; people are talking to each other. I think there's a desire to get back together … You can't be any more off the grid than a zombie."

More information about the "Zombie Apocalypse" classroom program is available at Texas Instruments' website: http://education.ti.com/en/us/stem-hollywood

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience , Facebook & Google+ . Original article on LiveScience.com

Our favorite compact dehumidifier is now under £40. Grab the ProBreeze Mini while you can

We have found the Hydrow Wave at a record-low price this Cyber Monday so watch us row away with glee

Cyber Monday 2024 camera deals live: Plus, savings on telescopes, binoculars and stargazing accessories

Most Popular

- 2 Canada wants your help to name its 1st moon rover

- 3 Meet 'Chameleon' – an AI model that can protect you from facial recognition thanks to a sophisticated digital mask

- 4 Space photo of the week: James Webb telescope spots a secret star factory in the Sombrero Galaxy

- 5 Can you get high from poppy seeds?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Last year, zoologist Philippe Fernandez-Fournier — from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada — and colleagues made a chilling discovery in the Ecuadorian Amazon. A...

Zombies are most certainly fake, but a few remarkable case studies suggest that some semblance of spontaneous resurrection is possible. In 2011, 46-year-old woman Kelly Dwyer fell into a frozen...

Nazi zombies make for a grabber of a headline, but what real evidence is there that raising the dead was on the agenda for even the most outrageous among the Nazis?

Real Life Zombies: Fact or Fiction? Movies may get some things right for a zombie apocalypse. Learn what science knows about real-life zombies and viruses, and if an apocalypse could happen - or not.

Using math, the group showed that only by quickly and aggressively attacking the zombie population could normal humans hope to prevent the complete collapse of society. That paper sparked further...

Well, we’ve previously discussed scientific studies on how fast a zombie-like virus could spread, as well as neurobehavioral disorders in humans that leave their sufferers mimicking some key...

Real zombies are out there — maybe in your own backyard! It may be fun to dress up like a zombie for Halloween, but real zombies do exist. They’re just not human.

Infectious proteins called prions could shut down parts of the brain and leave others intact, creating a zombie. iStock. Maybe, but it’s not going to be easy. In West African and Haitian...

From zombie dogs to mind control, here are some of the scariest experiments ever done. 1. Earth-swallowing black holes. When physicists first flipped the switch on the Large Hadron...

We caught up with Schlozman on Wednesday (Aug. 7) and learned how to diagnose the undead, and how to track a real-life zombie apocalypse.