Advertisement

Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2015

- Volume 22 , pages 107–125, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gabry Vanderveen 1 &

- Gwen van Eijk 2

57k Accesses

23 Citations

49 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Annoying paintings everywhere, [it] should be forbidden, and the perpetrators [should] clean everything with a toothbrush. It is pollution. There is an exception, what happens in cities, a boring wall is embellished with a nice painting made by experienced professional artists.

Introduction

The citation above, of a participant in our study who describes his first image of graffiti that comes to mind, summarizes our argument: public opinions on disorder (graffiti, in this case) may vary considerably, not only between people but people themselves make different judgments, depending on what they see in which context. Indeed, studies prove that ‘graffiti has been called everything from urban blight to artistic expression’ (Gomez 1993 : 634). Lombard ( 2012 ) calls graffiti ‘art crimes’ because it is criminal and artistic at the same time, which makes it also difficult to distinguish ‘artists’ from ‘criminals’. Even graffiti writers recognize that graffiti, while for them in the first place art, in some contexts is damaging or inappropriate (Rowe and Hutton 2012 ). According to Brighenti, graffiti is an ‘interstitial practice’: a practice about which different actors hold different conceptions, depending on how it is related to other practices such as ‘art and design (as aesthetic work), criminal law (as vandalism crime), politics (as a message of resistance and liberation), and market (as merchandisable product)’ ( 2010 : 316). A response to an interstitial practice always comes in a ‘yes, but’ form: graffiti is crime, or art — but it is always also something else (ibid.). Therefore, White ( 2000 : 253) argues, we should not condemn, nor celebrate graffiti, without considering ‘the ambiguities inherent in its various manifestations’.

Graffiti comes in many forms, varying from tag graffiti to artistic pieces and stencil art, and from illegal sprayings on public or private property to murals on legally designated walls. Our perspective is that there is no clear-cut distinction between graffiti and street art and that definitions based on form (e.g. tag, mural) cross legal definitions — the works of the (in)famous writer Banksy illustrate this point (Banksy’s work is often illegal but his work has also been sold and has featured in exhibitions, for example alongside Andy Warhol). Graffiti can be problematic, but not all graffiti is. The question as to when and why which forms of graffiti are perceived as criminal and by whom, remains an open question.

Yet, authorities, and many criminologists as well, tend to see graffiti as an unambiguous signal of disorder or even crime. Informed by the broken windows theory, many local governments seek to prevent and remove graffiti (e.g. Snyder 2006 ; Young 2010 ; Kramer 2010a ; Tempfli 2012 ; Uittenbogaard and Ceccato 2014 ). Studies in the tradition of the broken windows theory and social disorganization theory seem to assume that the public more or less agrees on what phenomena are ‘disorder’, and graffiti would be one of such phenomena. In this line of argument, ‘disorder’ would trigger fear (Ross and Jang 2000 ; Xu et al. 2005 ), undermine collective efficacy (Sampson et al. 1997 ; Kleinhans and Bolt 2013 ) and invite crime (Wilson and Kelling 1982 ; Wagers et al. 2008 ).

Our study engages with and critiques this line of argument in two ways. First, we observe that there has been much less attention for diverging (and conflicting) interpretations among the public. Many studies point at the mismatch of interpretations of graffiti as either art or crime between writers on the one hand and authorities, (supposedly) reflecting the concerns of the public, on the other hand (Whitford 1991 ; Gomez 1993 ; Halsey and Young 2006 ; Millie 2008 ; Snyder 2006 ; Dickinson 2008 ; Edwards 2009 ; Lombards 2012 ; McAuliffe 2012 ; Young 2012 ; Haworth et al. 2013 ). Indeed, we would expect that the perspective of graffiti writers differs from the perspective of the public (Brighenti 2010 ), as the underlying meaning and subcultural codes of graffiti are unknown to the average street user (Ferrell 2009 ; Young 2012 ). It is assumed that the uninformed public, as well as authorities and media, cannot distinguish one form of graffiti from another, thus interpreting all graffiti as evidence of increased gang activity, young people’s disrespect for authority or a threat to property values and neighbourhood safety (Ferrell 2009 ). However, in our study we show that opinions on disorder also vary significantly among the public. Based on qualitative and quantitative data we empirically unravel the different viewpoints on graffiti of the public in the Netherlands. Here we build on Millie’s ( 2011 ) work on value judgments in relation to criminalization.

Second, we elaborate insights on the role of context by examining judgments of graffiti in various micro places . Quantitative studies have generally examined context by focusing on the role of neighbourhood characteristics such as crime levels, population composition and stigma (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Franzini et al. 2008 ). We take a different approach and build on knowledge from mostly qualitative studies on context-related expectation and norms (e.g. Dixon et al. 2006 ; Cresswell 1996 ; Millie 2008 ). These studies draw our attention to the ways in which norms and expectations are tied to specific places, which together construct the meaning of places and of elements, such as graffiti, in those places. Using quantitative data, we investigate whether these ideas hold among a larger population (i.e. the Dutch public).

Studying responses to graffiti has broader relevance for research and policies on disorder, as graffiti is part of a larger ‘grey area’ of deviant behaviour that is not obviously criminal or harmful but nonetheless often labelled as ‘disorder’ (e.g. loitering, skateboarding, public drinking, noise). For example, following Jane Jacobs’ ( 1961 ) argument about the role of ‘eyes on the street’ in multifunctional neighbourhoods, people’s presence in the streets could contribute to safe street life and attract more people, but currently there is a tendency to see people hanging around in urban spaces as ‘social disorder’ (e.g. Ruggiero 2010 ; Binken and Blokland 2012 ). The same goes for public drinking: often banned in public space, but also tolerated when it contributes to the ‘aesthetic of the night-time economy’ (Dixon et al. 2006 ; Millie 2008 ). Particularly in the context of zero tolerance policies towards disorder, anti-social behaviour and incivilities, it is important to understand why and when behaviour is something that needs to be prevented, removed or punished. Critics of zero tolerance policies warn that in public space only certain behaviours from certain people are tolerated, while everything that deviates from the ‘mainstream’ is removed or excluded (e.g. Mitchell 2003 ; Beckett and Herbert 2008 ; MacLeod and Johnstone 2012 ). Diverging perspectives on disorder, graffiti included, lead to confusion about appropriate policy responses: if offensiveness is subjective, how can authorities discern what is acceptable and what is not? And to whom should authorities listen: to the majority, to those with most political or economic clout, or to more marginal groups who seem to struggle to enact their right to the city (Millie 2011 ; Kramer 2010a )? We return to these questions in the discussion. Before presenting our data, methods and results, we briefly discuss current trends in graffiti policy and criminological research on graffiti.

Graffiti as Art and/or Crime: Policy and Criminology

Even though ‘tough on graffiti’ approaches still dominate policies in countries such as Australia, the Netherlands, the UK and the US, the idea that the public responds in different ways to graffiti seems to be trickling down into policies, at least in some countries and cities. Repressive policies are concerned with preventing and removing graffiti, for example through applying special coatings and quickly removing all graffiti (e.g. Tempfli 2012 ; Uittenbogaard and Ceccato 2014 ). However, authorities have limited resources and thus need to prioritize which graffiti to remove first, which requires them to distinguish different types of graffiti (and for instance target offensive graffiti first, see Taylor et al. 2010 ; Vanderveen and Jelsma 2012 ). Moreover, local and national authorities do seem to distinguish between graffiti as a form of art and graffiti as crime, through mixing preventative and punitive measures with offering designated spaces for authorized graffiti (Kramer 2010b ; Lombard 2012 ; McAuliffe 2012 , 2013 ; Young 2010 ; Tempfli 2012 ). In some cities, graffiti (i.e. murals or pieces) is even used to prevent graffiti (Craw et al. 2006 ). Unwanted graffiti is in this way prevented and graffiti writers are offered alternatives. A bifurcated approach like this builds upon the idea that not all graffiti is received in the same way.

More generally, the way in which policy makers and citizens think about cities and a liveable urban environment is changing. Recent urban development seems to influence viewpoints on graffiti. Particularly the ‘creative city’ discourse offers opportunities to rethink the value of the creative practices of graffiti writers (McAuliffe 2012 ). Since Florida’s ( 2004 ) ‘recipe’ for successful cities (the 3 T’s in short: Technology, Tolerance and Talent — the latter T is measured by the share of people working in the creative sector), urban governments have promoted creativity in all forms and places to make their cities attractive. Indeed, in some places, graffiti in the form of murals is desired by policy makers to beautify locations and attract tourists (e.g. Millie 2011 ; Koster and Randall 2005 ; Zukin and Braslow 2011 ; McAuliffe 2012 ). However, city marketing may also result in a ‘get tough on graffiti approach’, as was the case in Melbourne in response to the run-up to the Commonwealth Games to be hosted in Melbourne in March 2006 (Young 2010 ). In London, authorities first painted over graffiti that mocked the Olympic Games and corporate sponsors, but recently commissioned graffiti as part of the Canals Project for East London’s waterways (Wainwright 2013 ). Such developments do not necessarily demonstrate a greater leniency towards graffiti. In the words of street artist Mau Mau: ‘when it suits them, they [the Council] choose who paints where’ (ibid.). So even when we may find that authorities are rethinking the meaning of graffiti, this is not necessarily applied to all graffiti in all places, which underscores our point that we need to consider responses to graffiti in relation to its form and context.

Given the ambiguity in how authorities deal with graffiti, we think it is striking that the dominant approach in criminological research on disorder views graffiti unambiguously as a social problem: something threatening that must be prevented and dealt with because it would cause fear and (more) crime. This idea is most common in studies following the ecological tradition (social disorganization theory) or the broken windows theory. Within ecological research, graffiti is often taken as an example of physical disorder (although it may also be seen as social disorder, see Skogan 1990 ), similar to other signs of physical disorder such as boarded-up houses, rubbish on the street and defaced bus stops. For example, in Wyant’s ( 2008 ) study on perceived incivilities and fear of crime, respondents were asked to indicate on a 4-point scale whether they thought various ‘neighbourhood problems’ capturing ‘perceived incivilities’ were a ‘serious problem’ in their neighbourhood, one of which is ‘graffiti on sidewalks and walls’ (see also, with varying questions or items: Ross and Jang 2000 ; Markowitz et al. 2001 ; Foster et al. 2010 ; Paquet et al. 2010 ; Gainey et al. 2011 ; Kleinhans and Bolt 2013 ).

Moreover, the broken windows theory suggests that graffiti and other signs of disorder in neighbourhoods cause not only fear but also crime, because fear would weaken social control and thus signal opportunities for crime to motivated offenders (Wilson and Kelling 1982 ; Wagers et al. 2008 ). A rare test of the assumed causal link between perceiving disorder and crime is the study of Keizer and colleagues ( 2008a ) which suggests that when people see norm transgression they are more likely to overstep a rule themselves. In one of the six field experiments, they demonstrate that in an environment with tag graffiti on a wall, people are more likely to litter, compared to a clean environment. However, Keizer and colleagues tested only for tag graffiti. They did consider different types of graffiti for their research design and decided on ‘simple tags as the more elaborated “pieces” might be perceived as art instead of norm violations’ (Keizer et al. 2008b ). However, while Keizer and colleagues acknowledge that different types of graffiti are valued differently, they still seem to assume that tag graffiti (as opposed to pieces) is always a norm violation, thus disregarding the variety of meanings, also to the public, of graffiti. While the broken windows thesis is popular among policy makers around the globe, the idea that there is a causal link between neighbourhood disorder and neighbourhood crime has been criticized (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Harcourt and Ludwig 2006 ). It is indeed questionable when we consider that disorder is an ambiguous phenomenon. However, even studies that do distinguish different graffiti types (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 : tags, political and gang graffiti; Foster et al. 2010 : on public property and on private property; Perkins and Taylor 1996 : graffiti on residential and non-residential property) usually combine the different types with items such as vandalism and litter to construct a scale measuring ‘physical disorder’. Thus, all graffiti, regardless of type and location, is taken as disorder.

However, there are indications that the public perceives and judges graffiti in different ways, too, which contrast the assumption that ‘the public’ never accepts graffiti. First, studies based on small, selective groups of respondents have suggested that the type of graffiti matters for whether people find it offensive and want it removed, or whether it invokes fear (Taylor et al. 2010 ; Austin and Sanders 2007 ; Campbell 2008 ). Furthermore, types of disorder may evoke different value judgments, as Millie ( 2011 ) has suggested. On what grounds do people reject or accept graffiti? And, in what types of environments do people judge graffiti negatively or positively? We now turn to these questions.

Data and Measurements

The research for this article is based on a study commissioned and financed by the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice and the Dutch Centre for Crime Prevention and Safety (CCV). They wanted insight into the public’s opinion on graffiti: what do people find offensive and what should authorities do about it? This study gave us the opportunity to examine the various ways in which people define graffiti and the role of context in relation to offensiveness (Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). In this article we elaborate several themes that we think are relevant for further research and policy decisions.

Participants

Our study measures the evaluation of different types of graffiti in different contexts among the Dutch public. The participants in this study (N = 881) are a random sample of the TNS NIPO access panel, which is a major Dutch sample source that includes approximately 200,000 people who can be invited via the internet to participate in research studies. Participants receive a small compensation for their time. The collection of data took place in September 2010. Around 50 per cent of the panel members that were invited by TNS NIPO took part via Computer Assisted Self Interviewing. Participants could fill in the survey from their computers at home, which took on average ten minutes. Age varies from 12 to 88 years ( m = 44.6; SD = 18.3), and 428 participants (49 per cent) are male and 453 (51 per cent) are female. All participants completed the entire survey. The data are weighed in terms of gender, age, education, family size and region, and are representative of the Dutch population.

Measurements

The survey was based on several qualitative and quantitative pilot studies (conducted by the first author) which indicated that two aspects are important for whether people find graffiti offensive or not: location and graffiti type (Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). For the current study we operationalized these aspects more systematically to test these first findings with a representative sample of the public.

The survey consisted of three parts which resulted in qualitative and quantitative data. The first part resulted in qualitative data. Participants were asked to describe in words the first ‘image’ of graffiti that occurred to them. They could type whatever they wanted: words, sentences and stories. The following parts resulted in quantitative data. The second part of the survey consisted of five general statements on graffiti for which participants indicated on a 7-point Likert scale to what extent they agreed (1) or disagreed (7). Statements included: ‘In general I am not disturbed by graffiti’ (recoded), ‘The presence of graffiti is a sign of crime’, ‘I feel safer in an environment where there is no graffiti’, ‘Graffiti is an art form’ (recoded) and ‘Graffiti is a common problem’. The statements together measure the general attitude regarding graffiti (α = .75); a higher score on the ‘general attitude scale’ indicates a more negative opinion about graffiti.

The third part of the survey used photos and/or short written descriptions of concrete examples of graffiti. Footnote 1 These examples were selected by the researchers based on findings from several pilot studies that included sorting tasks, interviews and a survey. Footnote 2 The 18 examples of graffiti varied for type (tags: little scribbles; throw ups: words in fat letters; pieces: colourful images; see Fig. 1 ) and location/context (a shop front; a house front; a skate park; a tunnel; a green space; an image without location). A (translated) list of the 18 examples is provided in the Appendix (photos can be viewed online in Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). No information was provided about whether the graffiti examples were legal or illegal, as participants would usually not know this in reality either. Participants were asked to evaluate the 18 examples of graffiti in two ways. First, they were asked to indicate their evaluation on a 7-point scale on three items: ‘This piece of graffiti is a form of disorder’, ‘This piece of graffiti is a form of crime’ and ‘This piece of graffiti should be removed as quickly as possible’. The sum score of the three items measures the extent to which that specific example of graffiti is perceived as disorder; a higher score on the ‘perceived disorder scale’ indicates more offensiveness (reliabilities vary from α = .89 to α = .97). Second, participants were asked to indicate which graffiti should be removed first. Participants were shown three sets of six photos and/or descriptions presenting the same type of graffiti in six different locations. This procedure was repeated for each of the graffiti types (tags, throw ups and pieces).

Example of piece, tag and throw up

We conducted a content analysis of the qualitative data that resulted from the open-ended question in the first part of the survey (which asked respondent to write down their first image of graffiti). Content analysis is a method that is used to systematically interpret large numbers of words and texts and can be used to code open-ended survey questions (Weber 1990 ). The central idea is that ‘the many words of texts can be classified into much fewer content categories’ (ibid.: 12). For this study we coded all responses to the open question in order to categorize their responses. We coded the data based on two content categories: valence (neutral, negative, positive and/or mixed) and value judgment (economic, aesthetic, prudential and/or moral; based on Millie 2011 , see below). The examples of responses for each of the content categories that we offer in the results section are meant to illustrate the categories but also to give the reader insight into our interpretation of the data. The coding process makes it possible to quantify qualitative data and enabled us to analyse how valence and value judgment are related by using descriptive statistics. The quantitative data generated in parts two and three of the survey were analysed by using descriptive statistics and variance analyses.

First Images and Value Judgments

The survey started with an open question asking participants what their first image was when thinking about graffiti. A small number of participants (9 per cent) was unable or unwilling to give a description of an initial image or idea of graffiti. Those who did provide their first ideas, varied greatly in their descriptions, especially in terms of specificity and approval or rejection of graffiti. A first reading of the data shows that many descriptions (whether neutral, positive or negative) refer to places: stations, tunnels, along highways, bridges, rail roads, fences, walls, trains, subways, doors — all places that are known to be popular spots for graffiti writers (e.g. Ferrell and Weide 2010 ). A first step of the content analysis was to categorize the descriptions in terms of valence, by sorting them based on whether they made a positive or negative statement, or gave a mixed or neutral description. More than half of the initial ideas on graffiti (52 per cent, n = 459) are neutral in tone. A total of 39 per cent (n = 341) of the participants give a description that involves an evaluative component: negative (17 per cent), positive (12 per cent) or both negative and positive (10 per cent).

A second step of our content analysis was to categorize the descriptions based on value judgments. Here we draw on Millie’s ( 2011 ) distinction of four different value judgments: moral, prudential, economic and aesthetic judgments. Millie argues that whether something is perceived as disorder or crime may be related to reasons other than legal or moral reasons and that it is essential to unravel the various value judgments for understanding why something is either condemned or condoned. Moral judgments refer to the good and the bad, right and wrong, which includes reference to legal norms. Prudential judgments concern one’s personal quality of life, whether something is enjoyable or makes life good for one. Economic judgments involve decisions on economic contributions. They are judgments about whether the behaviour, person or object, ‘makes an acceptable economic contribution to society’ or, in contrast, is costly (ibid.: 7). Aesthetic judgment is related to what is considered (or accepted as) beautiful or ugly, or as artistic, in that specific context. Millie here also refers to ‘everyday aesthetics’ related to ‘everyday objects, events and encounters’ (ibid.: 8). For example, ‘a degree of drunkenness may be tolerated (…) as it fits in with an aesthetic of the night-time economy’ (ibid.). Similarly, one type of graffiti may be accepted and even welcomed (e.g. pieces or murals) while others are seen as vandalism. For example, Millie shows that authorities in Toronto rejected graffiti based on economic judgments (as ‘vandalism’ would deter tourists), while they celebrated it based on aesthetic judgments (murals can beautify certain locations).

Together, the 341 participants made 440 value judgments. In line with what Millie ( 2011 ) found, value judgments are not mutually exclusive: some of the responses included more than one value judgment. We coded all value judgments separately (five per cent (n = 21) of the judgments could not be categorized). We then examined the relationship between valence and value judgment. Table 1 shows that an overwhelming majority of the positive evaluations involve aesthetic judgments, while this holds for a much smaller majority of the negative evaluations. Negative evaluations more often involve moral judgments.

Below we demonstrate our findings in more detail by offering examples of each of the value judgments. The positive descriptions based on an aesthetical value judgment mostly connect graffiti to beauty, art, form and colour, for example:

A beautifully painted wall in Asten. Robot-like figures, letters. Pretty drawings. Complete works of art on overpasses and the tracks. Beautiful art.

Positive prudential judgments involve the idea that something contributes to the quality of life of a person, for example, ‘I enjoyed [graffiti] because it was beautifully designed’ or ‘I see few graffiti in the neighbourhood, I miss art in the neighbourhood’. A couple of responses involved a positive moral judgment, for example: ‘[…] nothing wrong with it if it happens in places where it is allowed and then I generally find it nicely done’. None of the positive responses involve an economic judgment.

In the negative judgments, graffiti is associated for example with back streets, offensiveness, deterioration, defacement, impoverishment and anti-social behaviour and called untidy, messy, awful, a load of rubbish. Negative value judgments are also mostly related to aesthetics, but a substantial share refers to moral considerations and, to a lesser extent, prudential and economic judgments (see Table 1 ). Negative aesthetic judgments point at graffiti’s ugliness, amateurish nature or untidiness:

Mess on all public walls. Often no talent. Ugly and untidy. Dirty, scribbles on walls in the centre. Visual pollution.

Negative moral judgments involve referrals to the law and norms of behaviour, such as descriptions of graffiti as vandalism, referrals to private property, anti-social behaviour, foul language and racism:

Vandalism! I see graffiti everywhere and it annoys me because it is put on everything where it doesn’t belong. Keep off of other people’s stuff. Graffiti is mess created by stupid people who destroy other people’s properties by leaving their “tags”. Painting by youngsters without having permission to do so.

Negative prudential judgments involve statements such as ‘It annoys me’ and ‘Deterioration of the city’. We counted four economic judgments, all negative, which include descriptions of graffiti as ‘destroying’ private property.

A third category of descriptions offers both positive and negative judgments about graffiti. We can divide this category into two subcategories: those who make only aesthetic judgments and those who make an aesthetic and a moral judgment. Responses in the first subcategory for example say that graffiti can be beautiful or ugly, sometimes referring to type of graffiti or its location:

Cool!! Tag (not so nice), cool drawings, many colours, sometimes makes buildings or spaces nicer. Some graffiti is really artfully made, but most is just messing with a spray can. I find it (sometimes) beautiful. […] Not when it is mess on a wall with letters. That I call pollution.

In the second subcategory aesthetic and moral judgments are combined, which demonstrates respondents’ ambiguous position towards graffiti, also sometimes referring to type of graffiti or its location:

Graffiti can be really ugly but also really beautiful. Under a bridge it can brighten things up, but on houses or buildings I think it’s a shame (vandalism). […] On wanted and unwanted places, sometimes nice, sometimes ugly. Some graffiti is just artwork except racist slogans. Vandalism, but there are also nice works of art, depends on where it is sprayed.

Here we already see that context matters: it is not just the aesthetic quality of the graffiti itself but also its location. We return to this theme below. The quantitative data supports the wide variety in evaluations. The average score on the general attitude scale was neutral ( M = 4.05, SD = 1.21). However, answers to the individual items of the scale show participants’ ambiguity on the topic (see Table 2 ). For none of the statements there is an overwhelming majority towards disagreeing or agreeing. In addition, there is no clear tendency towards agreeing with either negative statements or positive statements. For example, the proportion of participants who agrees to being disturbed by graffiti is almost as large as the proportion of participants that disagrees. The share of respondents that is not disturbed by graffiti is about equal to the share that says they feel safer in an environment without graffiti. Finally, more than half of the participants agree that graffiti is an art form, while an equal share agrees with the next statement that graffiti is a common problem. The average neutral evaluation thus masks an enormous variety and contradictions in attitudes on graffiti. Footnote 3

Evaluations of Types of Graffiti

The open question suggests that participants distinguish between types of graffiti, for example by referring to tags or letters and pieces or paintings. Several studies confirm that the graffiti type matters for whether people find it offensive and want it removed, or whether graffiti invokes fear. Taylor et al. ( 2010 ) identified eight different types of graffiti based on the (textual) content of the graffiti. They made a distinction between, for example, the ‘memorial’ (words or statements that memorialize a deceased person) and the ‘obscene’ (words or statements that have an explicit, offensive sexual connotation). Their respondents, all directly involved with the removal and/or reporting of graffiti, indicated that all obscene, hate and threatening graffiti should be removed first. Austin and Sanders ( 2007 ) conducted a pilot study among undergraduate students using photography to examine the relation between graffiti and perceived safety. They found that four graffiti types (gang, hip hop style, message and murals) correspond to different levels of perceived safety: gang related graffiti evoked the lowest level of safety and murals the highest level. Based on in-depth interviews in focus groups, Campbell ( 2008 ) reports a similar finding, with tags being judged most negatively, followed by throw-ups and most positive judgment associated with pieces.

In our study we examined whether the findings of these small studies hold up in a large-scale systematic and quantitative study among a representative sample of the Dutch public. Responses to the 18 photos, which varied for type and location, shows that evaluations of specific examples of graffiti are more negative than the general attitudes suggest. Furthermore, the score on the perceived disorder scale differs significantly for different graffiti types: tags were evaluated most negatively, followed by throw ups, while pieces were evaluated least negative (Table 3 ). The ordering of graffiti types is generally the same for all six locations: regardless of the location, tags are perceived most negatively and pieces most positively (results not shown).

To further investigate the variety in evaluations, we analysed the standard deviation (SD) and kurtosis. We can take these measures as indications of consensus, or lack thereof, as they measure the distribution of values around the mean. The measures show that tags are not only evaluated most negatively: there is also most consensus among participants about their negative character. For pieces, on the other hand, opinions are on average neutral, but there is less consensus, which means that a larger group of participants tends to the negative and another group to the positive end of the scale. These patterns support the idea (also suggested by our qualitative data) that tags are more readily associated with illegality, which is more likely to be interpreted as negative, while pieces may also be related to art, in which case its quality depends on aesthetic judgments which can be either positive or negative depending on personal taste or artistic value. In other words, types of graffiti may evoke different value judgments (Millie 2011 ): pieces may be rejected mostly when they are of low aesthetic quality, while tags will be rejected mostly based on legal or behavioural norms.

The Role of Context: Graffiti in Micro Places

Norm transgression seems to be inherent to the practice of graffiti writing. That authorities frame graffiti as ‘out of place’ (Cresswell 1996 ) has ‘ensured that successive generations of predominantly young men have taken up graffiti as a risk-laden behaviour’ through which they can accrue fame and respect among peers (McAuliffe 2012 : 189). Nonetheless, as we have demonstrated, not all graffiti is considered to be offensive or a violation of norms to the same extent. We now turn to the question how context matters in how graffiti is received. The notion of context can be conceptualized in several ways. Many criminological studies focus on the role of neighbourhood characteristics in interpreting (signals of) behaviour (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Sampson 2012 ; Franzini et al. 2008 ). Some incidents and forms of disorder may act as ‘signal disorder’ and work as a warning signal for a greater danger, while others are just ‘background “noise” to everyday life’ (Innes 2005 : 192). Innes ( 2004 ) suggests that graffiti in an otherwise nice neighbourhood is more conspicuous than graffiti in an area where there is a variety of visible problems. On the other hand, in a (gentrifying) neighbourhood that is characterized as ‘edgy’, graffiti may be valued by those who appreciate such edginess (see e.g. Ferrell and Weide 2010 ; Dovey et al. 2012 ). Thus, graffiti in one neighbourhood is not the same as the same type of graffiti in another neighbourhood.

We take a different approach. Instead of focusing on the neighbourhood, we study the smaller setting. Several criminologists have underlined the need to study smaller geographical units such as street segments, (face) blocks and (micro) places (e.g. Eck and Weisburd 1995 ; Hipp 2007 ; Smith et al. 2000 ; Weisburd et al. 2012 ). Hipp ( 2007 ) suggests that it is likely that social and physical disorder are geographically localized: disorder in one block may not affect perceptions in the next. Cultural geographers have taken this further and investigate how meanings and practices are tied up with spaces (e.g. Sibley 1995 ; Cresswell 1996 ). Particularly, meanings attributed to places involve behavioural norms, thus leading to the ‘construction of normative places where it is possible to be either “in place” or “out of place”’ (Cresswell 2009 : 5). Such insights build on the work of Mary Douglas ( 1966 ) on the interpretation of dirt as signal of danger. Millie ( 2011 ) suggests that place and time matter particularly for ‘everyday aesthetics’. For example, certain behaviours or groups that are ‘untidy’ may be removed from tourist centres, business districts, shopping malls and exclusive neighbourhoods (Millie 2008 , 2011 ). In public space, certain behaviour, such as street drinking, may be seen as ‘“out of place” and consequently as morally offensive behaviour’ (Dixon et al. 2006 : 201). What is regarded to be ‘in place’ and what is ‘out of place’ depends on the behavioural expectations which vary among different contexts; outside we expect different behaviour than inside, for example (cf. Douglas 1966 ; see also Sibley 1995 ; Cresswell 1996 ). These studies point our attention to specific norms and expectations that are tied to specific places, but also suggests that we see graffiti as an element that, in connection with other elements, constructs the meaning of places.

An example of a context in which graffiti is ‘out of place’ is graffiti on a house front. Indeed, the photo showing graffiti on a house front is judged most negatively. Also, most participants seem to agree on this (greatest consensus indicated by the SD, second most consensus indicated by Kurtosis, see Table 3 ). This corresponds with what other scholars have observed: authorities seem to condemn graffiti mostly because it would ‘destroy’ or ‘devalue’ private property (Campbell 2008 ; Millie 2011 ).

Graffiti in a tunnel is ranked second (with average consensus) and thus evaluated more negatively than graffiti on a shop front. Here, we suggest, it is the sense of danger inherent to the location that reinforces the negative interpretation of graffiti. The photo shows a dark hole where one would enter the tunnel. It is possible that participants evaluate the tunnel in itself as a dangerous place, as concealment, shades and darkness in (urban and natural) environments often seem to invoke fear as they signify uncertainty (e.g. Blöbaum and Hunecke 2005 ). In this context, graffiti adds to danger and then is more likely to be interpreted negatively.

These two ways in which context plays a role may come together in evaluating graffiti in a skate park. This context is judged least negatively, but shows least consensus as indicated both by the SD and Kurtosis. That is, participants hold opposing opinions. On the one hand, we may expect that graffiti in a skate park is more readily accepted because it is seen as ‘in place’: graffiti is what one would expect in a skate park (Nolan 2003 ; cf. Cresswell 2009 ). For a group of participants this probably holds true and therefore they find it little problematic. On the other hand, skate parks themselves may be problematic locations, associated with young males (often in themselves problematic in public space, see e.g. Binken and Blokland 2012 ) and unruly behaviour (Karsten and Pel 2000 ; Nolan 2003 ; Chiu 2009 ). Participants who tend to the negative pole of the scale thus may evaluate this graffiti negatively because their evaluation of the whole setting is negative. If they find skate parks problematic, they are probably likely to find the graffiti in that context problematic, seeing the graffiti as a sign of problems that confirms to them the problems of skate parks.

Finally, we asked participants to prioritize graffiti for removal: we confronted them with six descriptions and/or photos, all showing the same type of graffiti but in six different locations and asked them which should be removed first. For the throw ups and pieces, the graffiti that is ‘out of place’ or applied in ‘dangerous places’ is chosen most often. For the throw ups, the top three consisted of the graffiti on the house front (40 per cent), the shop front (30 per cent) and in the tunnel (23 per cent). For the pieces, participants prioritized removal in the tunnel (54 per cent) and from the house front (25 per cent). The tunnel may have also been prioritized most often because of its negative content (the throw up spells ‘jerkhater’). We should note here that while our study presented different graffiti types in different locations, our study did not systematically vary type and graffiti (i.e. show the exact same graffiti in different locations and vice versa). The consequences of this approach are clear when we look at the responses to the tag photos. Unlike the photos of the pieces and throw ups, the tag category included a photo of racist tags. Clearly, when we asked respondents to prioritize removal, the content of the tags mattered most: a great majority of participants (84 per cent) chose the building with racist tags. The text included black scribbles saying ‘Geert Wilders’ (a Dutch right-wing anti-immigration politician), ‘Lonsdale’ (in the Netherlands, extreme right youth often wear clothes of the boxing label Lonsdale to express Nazi sympathies, see Grubben 2006 : 50), ‘WP’ (White Power), ‘NL’ (Netherlands, associated with White Power) and images of a swastika. Because the responses were heavily skewed towards the racist tags, we cannot say anything about the role of location for prioritizing the removal of tags. Clearly, offensiveness depends on a complex interaction between content, type and context.

We started this article with questioning the notion that the public usually views graffiti unambiguously as disorder, which is often the assumption underlying graffiti policy and many criminological studies on disorder. Based on qualitative and quantitative data on opinions regarding graffiti in the Netherlands, we showed that underneath a fairly neutral attitude towards graffiti there is great variation in evaluations, both between and within people, which indeed demonstrates graffiti’s ‘interstitial’ nature (‘it’s beautiful, but…’; ‘it’s criminal, but…’). We found that most evaluations were connected to two of the four value judgments that Millie ( 2011 ) distinguishes: positive evaluations are mostly connected to aesthetic qualities, while negative evaluations are connected to aesthetic and moral judgments. Few participants in their initial descriptions made prudential or economic considerations. This is perhaps surprising, given that local authorities often point to the costs of graffiti (damage, costs of removal) and to the effects of graffiti for the local environment (either as deterioration of neighbourhoods or as contributing to vibrant neighbourhoods). This is not to say that these considerations do not matter at all to the public, but it is not what first comes to mind.

Furthermore, we have shown that it matters what type of graffiti people see and in which context they see it. We presented participants with only three types of graffiti, not including murals and newer forms such as stencil art. Nonetheless, even considering these three graffiti types — the graffiti that policy makers seem most concerned about — judgments vary significantly. Moreover, it seems that the types and contexts of graffiti that are on average valued most positively, are also the types and contexts about which people seem to disagree the most. This further complicates the notion of unambiguous perceptions of disorder.

To round up we discuss three themes that we think warrant further attention. First, our study underlines the relevance of unravelling the role of context in interpreting behaviour and signals of behaviour, and what such signals in turn say about that particular context. Some practices, in our case graffiti, may or may not be viewed as disorder, and even when defined as such, may or may not signal crime or neighbourhood decay, depending on neighbourhood context (cf. Innes 2004 ; Sampson 2012 ). Our study complicates this argument: in addition to, and probably in relation to, neighbourhood context, context at the micro level shapes interpretations as well. Variation in situational appropriateness, place norms and physical features of places make any attempt to measure disorder ‘objectively’ problematic. We need more insight into the conditions under which people find certain behaviour frightening, annoying, criminal or acceptable and this includes investigating further how judgments of actions or behaviour relate to context, large and small. A combination of open-ended exploration with systematic questioning has additional value for both a general understanding of, and in-depth as well as contextual insight into attitudes and judgments.

Second, there is a tendency in studies on graffiti (and disorder more broadly) to assign certain viewpoints to certain groups: authorities, representing the public, who dislike graffiti versus writers who make graffiti. Actually, the policy practice is diffuse, and so is the opinion of the public. We suggest, building on Millie’s ( 2011 ) argument, that instead of distinguishing categories of people it may be more useful to distinguish the various value judgments that underpin the celebrating or criminalizing of practices. Insight into the various judgments can help structure the debate over whether graffiti should be tolerated, accepted or rather prevented and punished. That is, it matters for policy whether the objections are based on costs or damage that individuals (e.g. local entrepreneurs and home owners) are faced with, or the mere fact that it is against the law (even though people may like the graffiti and not experience any damage), or taste (that something is not ‘nice’ or ‘artistic’). In our study we found that approval and disapproval were based particularly on moral and aesthetic judgments and a combination of the two. These judgments imply different policy responses to graffiti: a first category of graffiti is unwanted because it is unlawful but in itself does not pose a problem (which could be translated into a more lenient policy), a second category of graffiti is unwanted solely because it is ‘ugly’ (which is a matter of personal taste; whether that is something for policy to regulate is an open question), and a third category of graffiti is unwanted because it is perceived as disorder or crime, or makes a place feel (even more) unsafe (to which policy could respond by removing it, demanding recovery of the damage by the writer, or negotiating with the writer to alter the graffiti — or even find other ways of making particular places safer).

However, and this is our third point, shifting from distinguishing groups or various stakeholders to distinguishing value judgments in itself does not help in thinking about who should decide and which value judgment should be valued most. This is not the place to answer that question, but we think that it is essential that authorities are (more) explicit, towards the public and towards graffiti writers, about which value judgments they deem important and legitimate. This may be of particular importance in the light of urban governments competing to be the most ‘creative’ city. On the one hand, this development seems to have led to more tolerance towards, or in any case a more nuanced view on, graffiti, which is translated into designated graffiti spaces and authorities commissioning graffiti projects. However, one could wonder whether this is merely replacing the decisive leverage of economic capital (graffiti as a threat to local economy and tourism) by cultural capital (graffiti as artistic and aesthetic value). We recall street artist Mau Mau who protested that the local authorities now decide ‘who paints where’ which has according to him led to ‘graffiti gentrification’ (Wainwright 2013 ). A more lenient policy may signify awareness to different views on what public space should look like and who may legitimately contribute to and alter it, but it may also be embraced merely because some graffiti contributes to the marketing of cities as creative places. In the latter case, we could question whether policies have in fact become more tolerant to different views. Insight into and an open debate about which value judgments matter in deciding what is accepted in public space and what not, may help to democratize decisions and explicate the (real) aims and views of local authorities about the place of graffiti in public space.

This research project also had another, methodological goal: to test the effect of textual descriptions versus visual representations of graffiti on evaluations and appreciation of the survey. To this end, three different versions of the survey were randomly administered: one including textual descriptions of the 18 examples of graffiti; another version showed 18 photographs and a third version used a combination of photographs and textual descriptions. Analyses of the three subsets revealed that participants did appreciate participating in the survey more when photos were included. However, variations in the survey design did not lead to significantly other findings in the context of the argument outlined here: evaluations of participants are comparable regardless of which version of the survey they filled out (Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). For the analyses here, we combine all versions.

In all these pilot studies as well as in the current study, photographs were used. These photographs were taken by criminology students, the researchers or found on the internet.

We also analysed possible relationships of sociodemographic variables with general attitude and the perceived disorder scale of the different graffiti types (Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). Overall, we did not find any strong relationship. Only age and gender had significant but small correlations, suggesting older people and men evaluate graffiti more negatively. This is for example indicated by the correlation between the general attitude scale (sum score) and age (e.g. ( r (881) = .19, p < .000). However, overall findings indicate that common sociodemographic variables do not vary systematically with attitudes towards graffiti.

Austin, D. M., & Sanders, C. (2007). Graffiti and perceptions of safety: a pilot study using photographs and survey data. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 14 (4), 292–316.

Google Scholar

Beckett, K., & Herbert, S. (2008). Dealing with disorder - social control in the post-industrial city. Theoretical Criminology, 12 (1), 5–30.

Article Google Scholar

Binken, S., & Blokland, T. (2012). Why repressive policies towards urban youths do not make streets safe: four hypotheses. Sociological Review, 60 (2), 292–311.

Blöbaum, A., & Hunecke, M. (2005). Perceived danger in urban public space. Environment and Behavior, 37 (4), 465–486.

Brighenti, A. M. (2010). At the wall: graffiti writers, urban territoriality, and the public domain. Space and Culture, 13 (3), 315–332.

Campbell, F. (2008). Good graffiti, bad graffiti? A new approach to an old problem. ENCAMS Research Report . Wigan: Environmental Campaigns.

Chiu, C. (2009). Contestation and conformity: street and park skateboarding in New York City public space. Space and Culture, 12 (1), 25–42.

Craw, P. J., Leland, L. S., Bussell, M. G., Munday, S. J., & Walsh, K. (2006). The mural as graffiti deterrence. Environment and Behavior, 38 (3), 422–434.

Cresswell, T. (1996). In place/out of place. Geography, ideology and transgression . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Cresswell, T. (2009). Place. In N. Thrift & R. Kitchen (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 169–177). Oxford: Elsevier.

Chapter Google Scholar

Dickinson, M. (2008). The making of space, race and place. Critique of Anthropology, 28 (1), 27–45.

Dixon, J., Levine, M., & McAuley, R. (2006). Locating impropriety: street drinking, moral order, and the ideological dilemma of public space. Political Psychology, 27 (2), 187–206.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo . London: Routledge & K. Paul.

Book Google Scholar

Dovey, K., Wollan, S., & Woodcock, I. (2012). Placing graffiti: creating and contesting character in inner-city Melbourne. Journal of Urban Design, 17 (1), 21–41.

Eck, J. E., & Weisburd, D. (1995). Crime Places in Crime Theory. In J. E. Eck & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Crime and place (Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 4, pp. 1–33). Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Edwards, I. (2009). Banksy’s graffiti: a not-so-simple case of criminal damage. Journal of Criminal Law, 73 (4), 345–361.

Ferrell, J. (2009). Hiding in the light: graffiti and the visual. Criminal Justice Matters, 78 (1), 23–25.

Ferrell, J., & Weide, R. D. (2010). Spot theory. City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 14 (1), 48–62.

Florida, R. L. (2004). The rise of the creative class: and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life . New York: Basic Books.

Foster, S., Giles-Corti, B., & Knuiman, M. (2010). Neighbourhood design and fear of crime: a social-ecological examination of the correlates of residents’ fear in new suburban housing developments. Health & Place, 16 (6), 1156–1165.

Franzini, L., Caughy, M. O., Nettles, S. M., & O’Campo, P. (2008). Perceptions of disorder: contributions of neighborhood characteristics to subjective perceptions of disorder. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28 (1), 83–93.

Gainey, R., Alper, M., & Chappell, A. (2011). Fear of crime revisited: examining the direct and indirect effects of disorder, risk perception, and social capital. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36 (2), 120–137.

Gomez, M. A. (1993). The writing on our walls: finding solutions trough distinguishing graffiti art from graffiti vandalism. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 26 (3), 633–708.

Grubben, G. (2006). Right-extremist sympathies among adolescents in the Netherlands. In P. Rieker, M. Glaser, & S. Schuser (Eds.), Prevention of right-wing extremism, xenophobia and racism in European perspective (pp. 48–66). Halle: Deutsches Jugendinstitut.

Halsey, M., & Young, A. (2006). 'Our desires are ungovernable' - writing graffiti in urban space. Theoretical Criminology, 10 (3), 275–306.

Harcourt, B. E., & Ludwig, J. (2006). Broken windows: new evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. University of Chicago Law Review, 73 (1), 271–320.

Haworth, B., Bruce, E., & Iveson, K. (2013). Spatio-temporal analysis of graffiti occurrence in an inner-city urban environment. Applied Geography, 38 , 53–63.

Hipp, J. R. (2007). Block, tract, and levels of aggregation: neighborhood structure and crime and disorder as a case in point. American Sociological Review, 72 (5), 659–680.

Innes, M. (2004). Signal crimes and signal disorders: notes on deviance as communicative action. British Journal of Sociology, 55 (3), 335–355.

Innes, M. (2005). What’s your problem - signal crimes and citizen-focused problem solving. Criminology & Public Policy, 4 (2), 187–200.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities . New York: Random House.

Karsten, L., & Pel, E. (2000). Skateboarders exploring urban public space: ollies, obstacles and conflicts. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 15 (4), 327–340.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008a). The spreading of disorder. Science, 322 (5908), 1681–1685.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008b). Supporting online material to The Spreading of Disorder. Science , http://www.sciencemag.org/content/322/5908/1681/suppl/DC1 . Accessed 18 Sept 2014.

Kleinhans, R., & Bolt, G. (2013). More than just fear: on the intricate interplay between perceived neighborhood disorder, collective efficacy, and action. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36 (3), 420–446.

Koster, R., & Randall, J. E. (2005). Indicators of community economic development through mural-based tourism. Canadian Geographer-Geographe Canadien, 49 (1), 42–60.

Kramer, R. (2010a). Moral panics and urban growth machines: official reactions to graffiti in New York City, 1990–2005. Qualitative Sociology, 33 (3), 297–311.

Kramer, R. (2010b). Painting with permission: legal graffiti in New York City. Ethnography, 11 (2), 235–253.

Lombard, K.-J. (2012). Art crimes: the governance of hip hop graffiti. Journal for Cultural Research, 17 (3), 255–278.

MacLeod, G., & Johnstone, C. (2012). Stretching urban renaissance: privatizing space, civilizing place, summoning 'community'. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36 (1), 1–28.

Markowitz, F. E., Bellair, P. E., Liska, A. E., & Liu, J. H. (2001). Extending social disorganization theory: modeling the relationships between cohesion, disorder, and fear. Criminology, 39 (2), 293–320.

McAuliffe, C. (2012). Graffiti or street art? Negotiating the moral geographies of the creative city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34 (2), 189–206.

McAuliffe, C. (2013). Legal walls and professional paths: the mobilities of graffiti writers in Sydney. Urban Studies, 50 (3), 518–537.

Millie, A. (2008). Anti-social behaviour, behavioural expectations and an urban aesthetic. British Journal of Criminology, 48 (3), 379–394.

Millie, A. (2011). Value judgments and criminalization. British Journal of Criminology, 51 (2), 278–295.

Mitchell, D. (2003). The right to the city: social justice and the fight for public space . New York: Guilford Press.

Nolan, N. (2003). The ins and outs of skateboarding and transgression in public space in Newcastle, Australia. Australian Geographer, 34 (3), 311–327.

Paquet, C., Cargo, M., Kestens, Y., & Daniel, M. (2010). Reliability of an instrument for direct observation of urban neighbourhoods. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97 (3), 194–201.

Perkins, D. D., & Taylor, R. B. (1996). Ecological assessments of community disorder: their relationship to fear of crime and theoretical implications. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24 (1), 63–107.

Ross, C. E., & Jang, S. J. (2000). Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28 (4), 401–420.

Rowe, M., & Hutton, F. (2012). ‘Is your city pretty anyway?’ Perspectives on graffiti and the urban landscape. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 45 (1), 66–86.

Ruggiero, V. (2010). Social disorder and the criminalization of indolence. City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 14 (1), 164–169.

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105 (3), 603–651.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighbourhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277 , 918–924.

Sibley, D. (1995). Geographies of exclusion: Society and difference in the West . London: Routledge.

Skogan, W. G. (1990). Disorder and decline: Crime and the spiral of decay in American neighborhoods . New York: Free Press.

Smith, W., Frazee, S., & Davison, E. (2000). Furthering the integration of routine activity and social disorganization theories: small units of analysis and the study of street robbery as a diffusion process. Criminology, 38 (32), 489–523.

Snyder, G. J. (2006). Graffiti media and the perpetuation of an illegal subculture. Crime, Media, Culture, 2 (1), 93–101.

Taylor, M. F., Cordin, R., & Njiru, J. (2010). A twenty-first century graffiti classification system: a typological tool for prioritizing graffiti removal. Crime Prevention & Community Safety, 12 , 137–155.

Tempfli, E. (2012). Reacties op graffiti. Graffitibeleid bij gemeenten en openbaar vervoersbedrijven . [Responses to graffiti. Graffiti policy among muncipalities and public transport companies.] The Hague: Ministry of Security and Justice.

Uittenbogaard, A., & Ceccato, V. (2014). Safety in Stockholm’s underground stations: an agenda for action. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 20 (1), 73–100.

Vanderveen, G. N. G., & Jelsma, F. (2011). Graffiti in beeld. Eindrapportage. [A view on graffiti. Final report.] Leiden/Utrecht: Universiteit Leiden/ Centrum voor Criminaliteitspreventie en Veiligheid. http://www.hetccv.nl/binaries/content/assets/ccv/instrumenten/graffiti/graffiti_in_beeld_eindrapportage_definitief.pdf . Accessed 9 Aug 2015.

Vanderveen, G. N. G., & Jelsma, F. (2012). Kunst en/of criminaliteit. De ene graffiti is de andere niet. [Art and/or crime. All graffiti is not the same.]. Tijdschrift voor Veiligheid, 11 (3), 3–19.

Wagers, M., Sousa, W., & Kelling, G. (2008). Broken windows. In R. Wortley & L. Mazerolle (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (pp. 247–262). Cullompton: Willan.

Wainwright, O. (2013). Olympic legacy murals met with outrage by London street artists. (2013, 6 August). The Guardian . http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/aug/06/olympic-legacy-street-art-graffiti-fury . Accessed 18 Sept 2014.

Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412983488 .

Weisburd, D., Groff, E., & Yang, S.-M. (2012). The criminology of place : Street segments and our understanding of the crime problem . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

White, R. (2000). Graffiti, crime prevention & cultural space. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 12 (3), 253–168.

Whitford, M. J. (1991). Getting rid of graffiti: A practical guide to graffiti removal and anti-graffiti protection . London: E & F N Spon.

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. The Atlantic Monthly (February), 46–52.

Wyant, B. R. (2008). Multilevel impacts of perceived incivilities and perceptions of crime risk on fear of crime - isolating endogenous impacts. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45 (1), 39–64.

Xu, Y. L., Fiedler, M. L., & Flaming, K. H. (2005). Discovering the impact of community policing: the broken windows thesis, collective efficacy, and citizens’ judgment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42 (2), 147–186.

Young, A. (2010). Negotiated consent or zero tolerance? Responding to graffiti and street art in Melbourne. City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 14 (1), 99–114.

Young, A. (2012). Criminal images: the affective judgment of graffiti and street art. Crime, Media, Culture, 8 (3), 297–314.

Zukin, S., & Braslow, L. (2011). The life cycle of New York’s creative districts: reflections on the unanticipated consequences of unplanned cultural zones. City, Culture and Society, 2 (3), 131–140.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this work was supported by the Ministry of Security and Justice of the Netherlands and the Dutch Centre for Crime Prevention and Safety.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Recht op Beeld, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Gabry Vanderveen

Institute for Criminal Law and Criminology, Leiden Law School, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

Gwen van Eijk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gwen van Eijk .

Participants were asked to evaluate the following 18 examples of graffiti (photos can be viewed online in Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 : 32):

A large image in multiple colours of a lion in football outfit and a ball with above the word ‘Holland’ on the wall of a house.

A word ‘HDG’ of thick letters in multiple colours on the wall of a house.

Scribbles of ‘Geert Wilders’, ‘Lonsdale’, ‘WP’, ‘NL’ and swastika’s in black on a building.

A tunnel with on the walls many images in multiple colours among which a skull, words in thick letters and scribbles.

Various words in thick letters in multiple colours on attributes of a skate park.

Images in multiple colours of a women’s head and a snake’s head on a wall with bushes and grass in front of it.

Many scribbles and words in thick letters in multiple colours on columns and walls under a viaduct.

A word of large thick letters in blue and white on a wall with bushes in front of it.

A number of scribbles in black on a bin in a green field with bushes.

A word ‘horkhater’ [translates as ‘jerkhater’] in thick letters in black and white on a viaduct.

A word of four thick rounded rectangular letters in multiple colours.

A word in thick round letters together with scribbles in multiple colours on a shutter of a take-away restaurant.

A large image in multiple colours of a fantasy face on the door of a dive shop.

Various scribbles and signs in diverse colours on top of each other.

Scribbles in diverse colours on a shutter of a phone shop.

An image in multiple colours of a boy and a skateboard on the back of a hill in a skatepark.

Image in multiple colours of a fantasy figure in a t-shirt and shorts.

Multiple scribbles in various colours on a hill in a skatepark.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Vanderveen, G., van Eijk, G. Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder. Eur J Crim Policy Res 22 , 107–125 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9288-4

Download citation

Published : 10 September 2015

Issue Date : March 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9288-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Micro place

- Perceptions

- Value judgment

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Art through the Colors of Graffiti: From the Perspective of the Chromatic Structure

Claudia feitosa-santana, carlo m gaddi, andreia e gomes, sérgio m c nascimento.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected]

Received 2020 Jan 28; Accepted 2020 Apr 19; Collection date 2020 May.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Graffiti is a general term that describes inscriptions on a wall, a practice with ancient origins, ranging from simple drawings and writings to elaborate pictorial representations. Nowadays, the term graffiti commonly describes the street art dedicated to wall paintings, which raises complex questions, including sociological, legal, political and aesthetic issues. Here we examine the aesthetics of graffiti colors by quantitatively characterizing and comparing their chromatic structure to that of traditional paintings in museums and natural scenes obtained by hyperspectral imaging. Two hundred twenty-eight photos of graffiti were taken in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. The colors of graffiti were represented in a color space and characterized by several statistical parameters. We found that graffiti have chromatic structures similar to those of traditional paintings, namely their preferred colors, distribution, and balance. In particular, they have color gamuts with the same degree of elongation, revealing a tendency for combining similar colors in the same proportions. Like more traditional artists, the preferred colors are close to the yellow–blue axis of color space, suggesting that graffiti artists’ color choices also mimic those of the natural world. Even so, graffiti tend to have larger color gamuts due to the availability of a new generation of synthetic pigments, resulting in a greater freedom in color choice. A complementary analysis of graffiti from other countries supports the global generalization of these findings. By sharing their color structures with those of paintings, graffiti contribute to bringing art to the cities.

Keywords: color aesthetics, color statistics, color calibration, cultural heritage and art, graffiti, spectral imaging, street art

1. Introduction

Graffiti is a mass noun generally used to describe writings or drawings made on walls to be publicly seen, from the ancient inscriptions to the social phenomenon of tagging names in public locations [ 1 , 2 ]. The term has become even more elastic and in recent decades has also been used to refer to a contemporary form of visual art, usually wall paintings, done illegally or commissioned, in public spaces [ 3 ]. There is no consensus in the terminology that describes this more art-related meaning, and this type of graffiti is often called graffiti art [ 4 ], independent public art [ 5 ], or the most known and general term, street art [ 6 ]. In this study, we are concerned with the art expression, and the term graffiti will refer to paintings on public walls, either unsanctioned as in some definitions [ 1 ] or sanctioned, as many are nowadays [ 3 ].

Whether graffiti are art or visual pollution is still debatable [ 6 ]. Negative views relate in general to tagging on public locations [ 7 , 8 ]. Positive views relate to their role in bringing art to the urban environment [ 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ] and wellbeing to its habitants [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. For the scholars, graffiti is considered a new kind of cultural production [ 11 , 17 ] which extrapolates the boundaries of traditional art—“the white cube of the museum”—and makes the city—“the gray cube of the street”—a canvas in an open museum [ 18 ]. Moreover, the money involved with the increasing number of famous graffiti artists—e.g., the Banksy canvas “Devolved Parliament” was auctioned for approximately 12 million USD on 3 October, 2019 [ 19 ]—and the legal debate about whether the land owner or the graffiti artist owns the graffiti [ 20 , 21 ] clearly express the relevance of graffiti. In any case, its study is now legitimated as a research subject among scholars in the academia [ 3 , 22 ] with dedicated scientific journals such as the Street Art & Urban Creativity founded in 2015 [ 23 ].

Art, of course, cannot be simply quantified, as it is a complex multidimensional experience [ 24 , 25 ]. It is possible, however, to measure certain properties of artworks, such as the spatial structure [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ] and the color structure [ 30 , 31 , 32 ], and to look for regularities shared by artworks.

The goal of this study was to quantitatively characterize the colors of graffiti and to compare their color structure to that of traditional paintings that are found in museums. We photographed a representative sample of graffiti in different regions of São Paulo, Brazil, with colorimetric precision and analyzed several properties of their color structure. We compared this analysis with a similar analysis of traditional paintings. We found evidence that graffiti and traditional paintings have several color properties in common, suggesting that graffiti represent what is considered art and, therefore, bring art to the cities.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. study area and image acquisition.

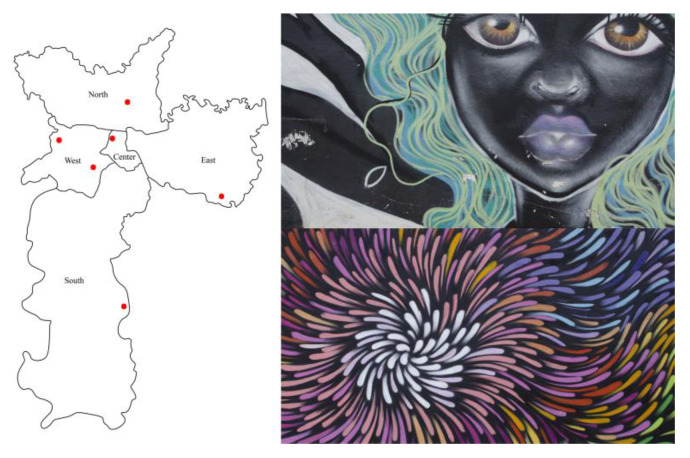

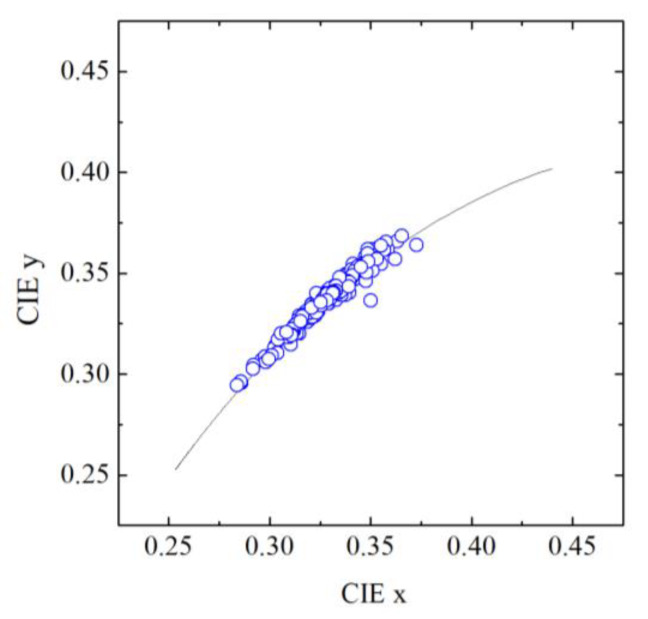

Photos of 245 graffiti of the city of São Paulo, Brazil, were taken in five different zones of the city. Figure 1 shows the locations of these zones on a map of the city as well as some examples of graffiti. From this sample, 17 photos were excluded because of the impossibility to apply the colorimetric calibration due to the non-uniform illumination. Thus, a total of 228 graffiti were analyzed in this study: 26 from the north, 59 from the south, 44 from the east, 44 from the west, and 55 from the center. These photos were taken during the month of October around the middle of the day in order to avoid shade as much as possible. The areas were chosen to represent the diversity of styles, following the advice of local recognized graffiti artists. In each area, the graffiti were photographed in the exact sequence in which they were present in each alley, avoiding subjective aesthetics judgements from the authors of this work. Monochromatic or unevenly illuminated graffiti were not considered.

Left : red dots indicate the areas within the five zones of the city of São Paulo where the photos of the graffiti were taken. In total, 228 photos were analyzed in the study: 26 from the north, 59 from the south, 44 from the east, 44 from the west, and 55 from the center. The areas were chosen to represent the diversity of styles and selected under the advice of local recognized graffiti artists. Right : two examples of graffiti in our sample.

The camera was a Nikon D7000 with a resolution of 4928 × 3264 pixels, and the optical conditions were such that the average resolution of the system was about 0.5 mm per pixel. An X-Rite Macbeth ColorChecker Classic with 24 samples was included in the field of view of each photo as shown in Figure 2 . The ColorChecker was used for calibration purposes, for both colorimetric calibration and spatial scaling. For colorimetric calibration, the spectral irradiance on the color chart was measured immediately before taking the photo with a portable spectro-colorimeter Everfine SPIC-200, in the spectral range from 380 to 760 nm.

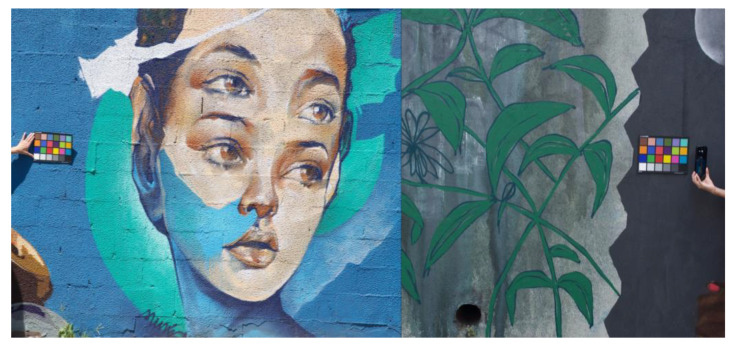

Illustration of the procedure of image acquisition. Left : acquiring the image with the X-Rite Macbeth ColorChecker Classic included in the field of view of the photo for colorimetric calibration and spatial scaling purposes. Right : acquisition of the illumination spectrum on the color chart with a portable spectro-colorimeter Everfine SPIC-200 for colorimetric calibration (the moment right before the photo).

2.2. Colorimetric Calibration of the Photos

Images were converted from raw camera NEF format to DNG and then converted to sRGB (standard RGB). For the colorimetric calibration, the spectral reflectance of the samples of the color checker were measured in the laboratory with a spectrophotometer Minolta CM 2600d (Konica Minolta Co. Lda., Japan) and used to obtain the exact colors of the patches of the color checker under each local illumination measure at the time of image acquisition for each photo. These data were then used to correct the sRGB data from the camera for each photo using a polynomial regression with least squares fitting with a three-term polynomial [ 33 , 34 ]. The average color error across all 228 photos of the color chart was 6.3 ΔE units before the colorimetric correction. This value was obtained by computing the real colors of the 24 samples of the color chart and comparing with the ones obtained from the camera. After the colorimetric correction, this value was reduced to 4.0 ΔE units, a number that is just a little above the visual limit of 2.2 ΔE to perceive color changes in complex images [ 35 , 36 ].

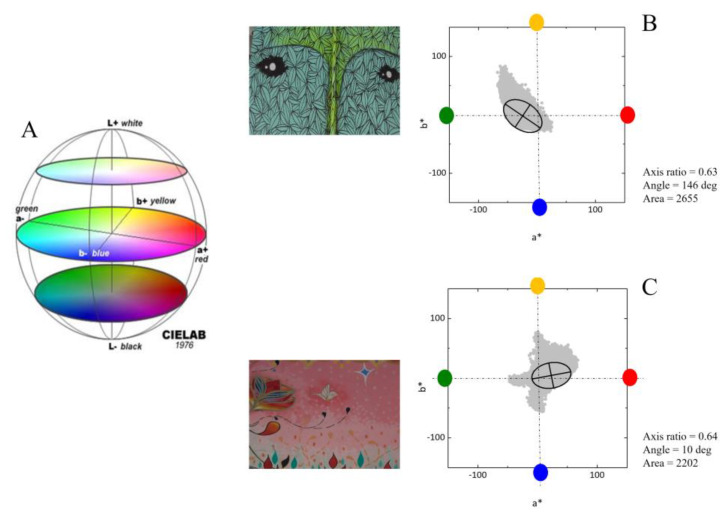

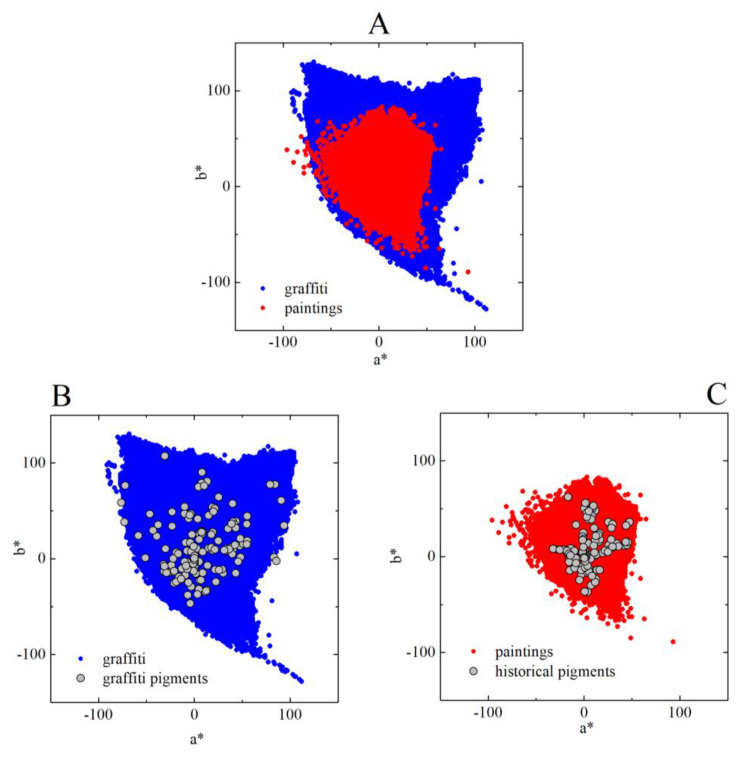

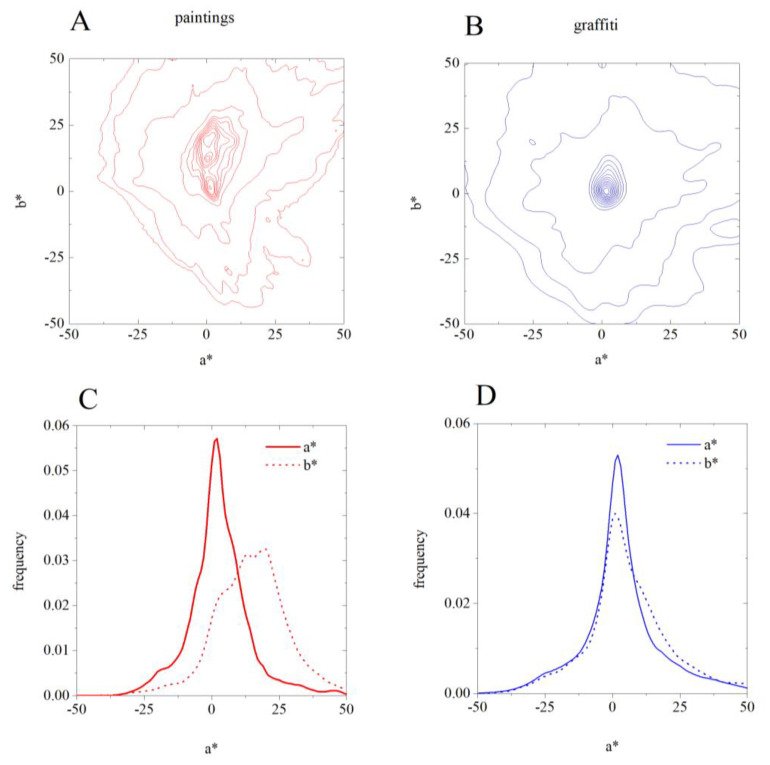

The corrected colors of each pixel were represented in the CIELAB color space [ 37 , 38 ]. We selected this color space because it is a perceptual space, i.e., it represents perceptions rather than physical variables, and because it is reasonably uniform in the sense that has the same metric across all space. Figure 3 A illustrates the three dimensions of this color space: L*, lightness; a*, red–green dimension; and b*, yellow–blue dimension. Figure 3 B,C illustrates the representation of the color gamut of two graffiti represented in the (a*, b*) plane of the color space. In this work we were not concerned with lightness, the L* component, but were solely concerned with the chromatic dimensions defined in the plane (a*, b*).

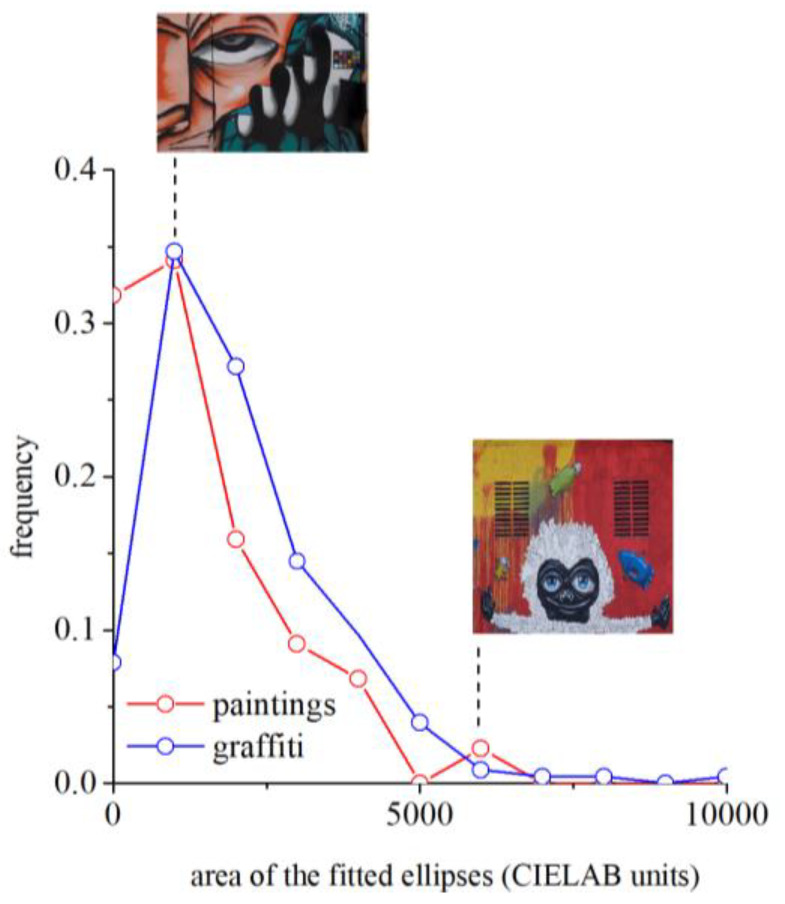

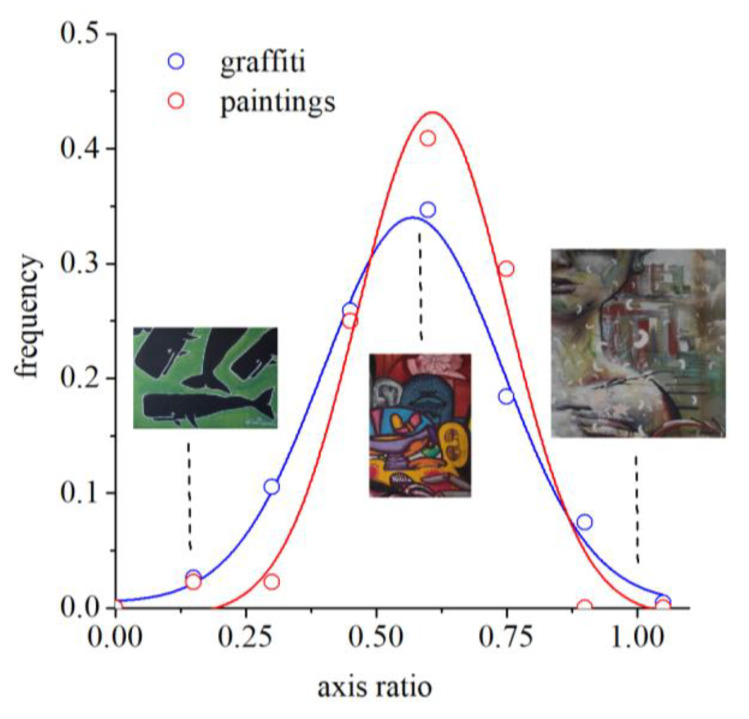

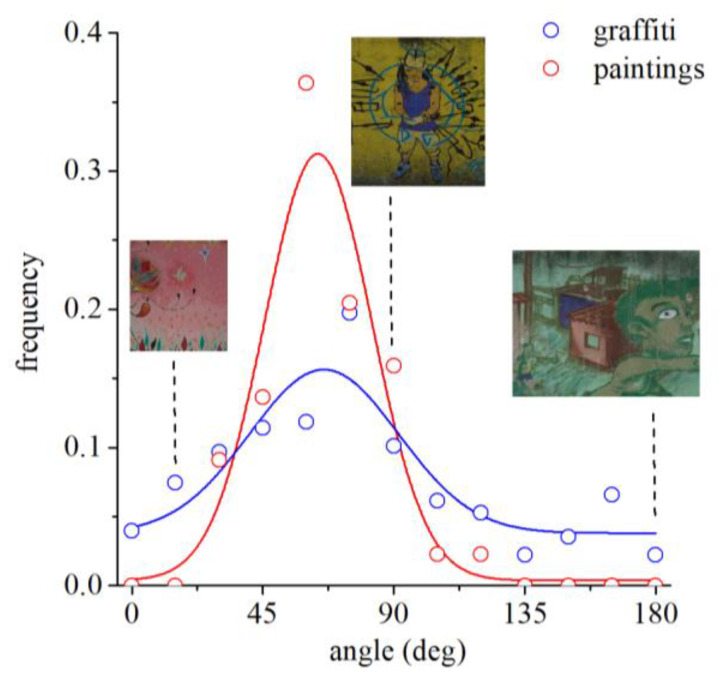

( A ) The color space CIELAB. ( B , C ) The representation of the color gamut of two examples of graffiti in the color plane of the color space. The color of each direction—red, green, yellow and blue—is indicated in the graphs. The upper graffiti ( B ) has more greens and yellows, and the lower graffiti ( C ) has more reds, properties that define how the color gamut is represented in the color space. To characterize the geometry of the color gamut with few parameters we fitted ellipses to the gamut such that the major and minor axes were aligned with the principal directions. The axes sizes were twice the standard deviation. The axis ratio was the result of the minor divided by the major axis. The angle was defined between the major axis and the positive a* axis. The area is proportional to the number of colors in the graffiti.

To characterize the structure and geometry of the color gamut with few parameters we computed the directions of the principal components [ 39 , 40 ] and, for visualization purposes, represented ellipses such that the major and minor axes were aligned with these directions and were twice the corresponding standard deviations. These ellipses capture the variability of the colors across the two principal directions in the color space. They take into account not only the extent of the gamut but also the distribution of the colors within the gamut. On average, across all graffiti, these ellipses contain about 80% of all colors of the gamut as a consequence of the fact that the axes are twice the standard deviations. Figure 3 B,C illustrates the ellipses corresponding to the gamuts of two graffiti. Note that the directions of the principal components reflect both the extent of the colors in the color plane and their frequency of occurrence. The degree of elongation of the ellipse can be quantified by the axis ratio, the ratio of the minor axis to the major axis, and captures the balance between the colors in the gamut. In the examples shown, axis ratios are around 0.6, showing a moderate degree of elongation. The range of more abundant colors can be captured by the angle of the major axis with the positive a* axis. A red–green variation is expressed by angles around 180° (or 0°), and a yellow–blue variation is expressed by angles around 90° (or 270°).

2.3. Comparison with Traditional Paintings

The data obtained from the analysis of graffiti were compared with similar data obtained from hyperspectral imaging of paintings. The 44 paintings were from several epochs, from the Renaissance to the mid 20th century. They encompassed several styles, from figurative to abstract, and were from both famous and anonymous artists. They were digitalized by a hyperspectral imaging system in the spectral range 400 to 720 nm with a resolution of 10 nm. The spatial resolution was 1344 × 1024 pixels and the conditions of acquisition produced a resolution about 0.3 min visual angle per pixel, close to that of the human eye. Details about the paintings and digitalization methodology are described elsewhere [ 30 , 31 , 41 ]. The spectral reflectance of each pixel was estimated, and the corresponding spectral radiance was obtained assuming the standard illuminant D65. The corresponding color was then computed and expressed in the CIELAB color space following the same procedure as for graffiti.

2.4. Spatial Calibration