'Invisible Gorilla' Test Shows How Little We Notice

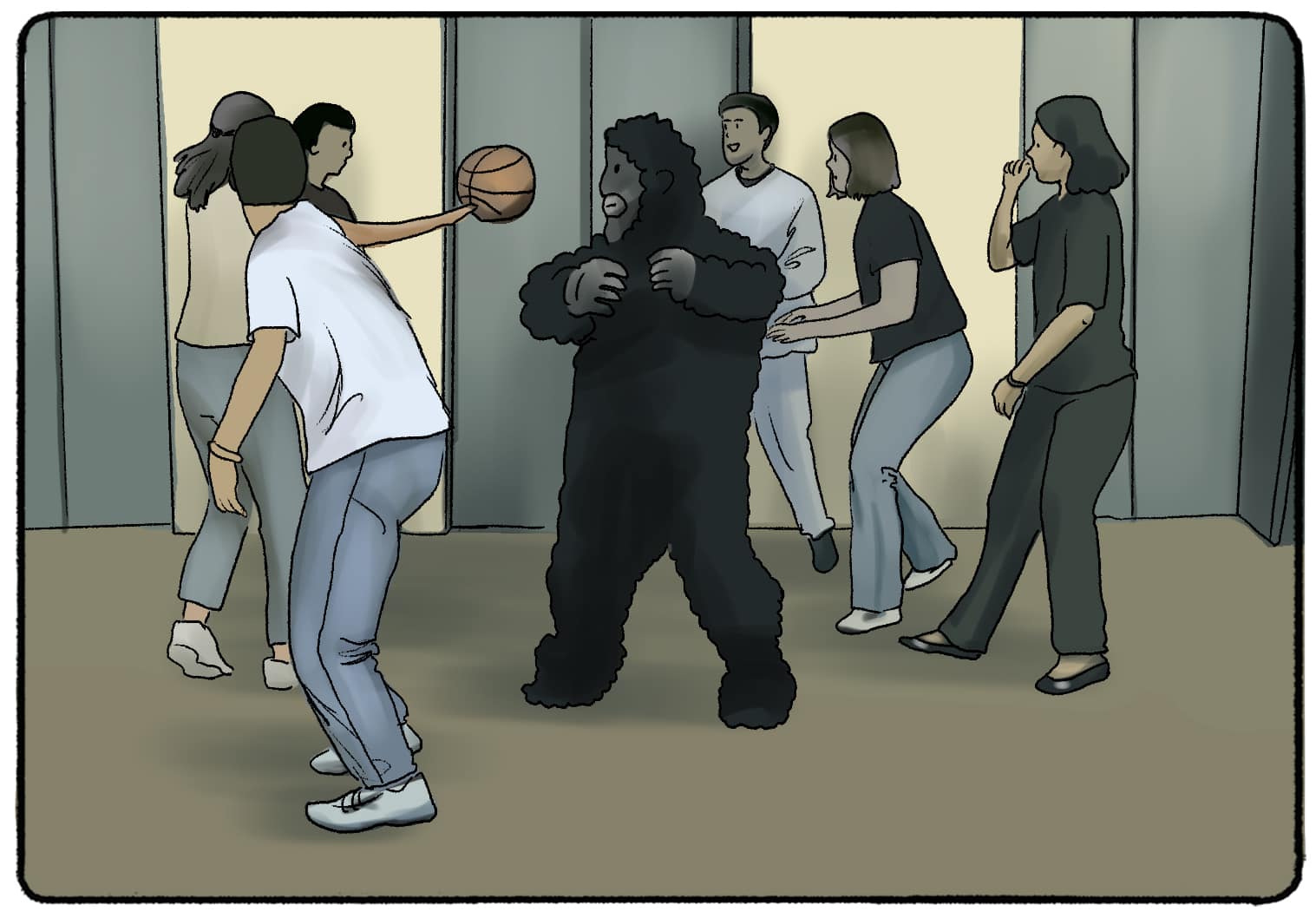

A dumbfounding study roughly a decade ago that many now find hard to believe revealed that if people are asked to focus on a video of other people passing basketballs, about half of watchers missed a person in a gorilla suit walking in and out of the scene thumping its chest.

Now research delving further into this effect shows that people who know that such a surprising event is likely to occur are no better at noticing other unforeseen events — and may even be worse at noticing them — than others who aren't expecting the unexpected.

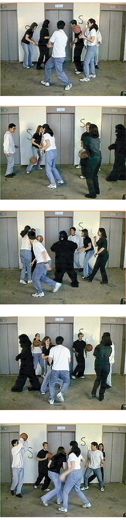

The so-called "invisible gorilla" test had volunteers watching a video where two groups of people — some dressed in white, some in black — are passing basketballs around. The volunteers were asked to count the passes among players dressed in white while ignoring the passes of those in black. (To watch the video for yourself, click here .)

{{ embed="20100711"

These confounding findings from cognitive psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris detailed in a 1999 study revealed how people can focus so hard on something that they become blind to the unexpected, even when staring right at it. When one develops "inattentional blindness," as this effect is called, it becomes easy to miss details when one is not looking out for them.

"Although people do still try to rationalize why they missed the gorilla, it's hard to explain such a failure of awareness without confronting the possibility that we are aware of far less of our world than we think," Simons told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gorilla infamy

Of course, these results are utterly counterintuitive, with 90 percent of people now predicting that they would notice the gorilla in the video. The problem is that this video has become so famous that many people know to look for a gorilla when asked to count basketball passes.

In new research, Simons decided to use the infamy of the invisible gorilla to his advantage, creating a similar video that asked for the same results from the audience.

"I thought it would be fun to see if I could monkey with people's intuitions again using almost the same task," Simons said.

(Stop now! Before reading further, try his test out here .)

The idea with this new video was to see if those who knew about the invisible gorilla beforehand would be more or less likely to notice other unexpected events in the same video.

"You can make two competing predictions," Simons said. "Knowing about the invisible gorilla might increase your chances of noticing other unexpected events because you know that the task tests whether people spot unexpected events. You might look for other events because you know that the experimenter is up to something." Alternatively, "knowing about the gorilla might lead viewers to look for gorillas exclusively, and when they find one, they might fail to notice anything else out of the ordinary."

Expecting the unexpected

Of the 41 volunteers Simon tested who had never seen or heard about the old video, a little less than half missed the gorilla in the new video, much like what happened in the old experiments. The 23 volunteers he tested who knew about the original gorilla video all spotted the fake ape in the new experiment.

However, knowing about the gorilla beforehand did not improve their chances of detecting other unexpected events. Only 17 percent of those who were familiar with the old video noticed one or both of the other unexpected events in the new video. In comparison, 29 percent of those who knew nothing of the old video spotted one of the other unexpected events in the new video.

"This demonstration is much like a good magic trick in which a magician repeatedly makes a ball disappear," Simons said. "A magician can lead the audience to think he's going to make the ball disappear with one method, and while people watch for that technique, he uses a different one. In both cases, the effect capitalizes on what people expect to see, and both demonstrate that we often miss what we don't expect to see."

"A lot of people seem to take the message of our original gorilla study to be that people don't pay enough attention to what is happening around them, and that by paying more attention and 'expecting the unexpected,' we will be able to notice anything important," he added. "The new experiment shows that even when people know that they are doing a task in which an unexpected thing might happen, that doesn't suddenly help them notice other unexpected things."

Once people find the first thing they're looking for, "they often don't notice other things," Simons said. "Our intuitions about what we will and won't notice are often mistaken."

Simons detailed his new findings online July 12 in the journal i-Perception.

- World's Greatest Illusions

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

What do you know about psychology's most infamous experiments? Test your knowledge in this quiz.

'Mystery disease' in Congo turned out to be malaria — and potentially, another disease

NASA's Parker Solar Probe will reach its closest-ever point to the sun on Christmas Eve

Most Popular

- 2 Everything you need to know about digiscoping

- 3 MIT's massive database of 8,000 new AI-generated EV designs could shape how the future of cars look

- 4 'Rising temperatures melted corpses out of the Antarctic permafrost': The rise of one of Earth's most iconic trees in an uncertain world

- 5 Space photo of the week: James Webb and Chandra spot a cosmic 'Christmas Wreath' sparkling in the galaxy next door

The Invisible Gorilla (Inattentional Blindness)

If you're here, you probably already know a bit about the Invisible Gorilla video and how it relates to attention. Did you know this experiment supports a fascinating concept called "inattentional blindness?"

What Is The Invisible Gorilla Experiment?

In 1999, Chris Chabris and Dan Simons conducted an experiment known as the “Invisible Gorilla Experiment.” They told participants they would watch a video of people passing around basketballs. In the middle of the video, a person in a gorilla suit walked through the circle momentarily.

The researchers asked participants if they would see the gorilla. Of course, they would, right? Not so fast. Before the researchers asked participants to watch the video, they asked them to count how many times people in the white shirts passed the basketball. In this initial experiment, 50% of the participants failed to see the gorilla!

The Invisible Gorilla and Inattentional Blindness

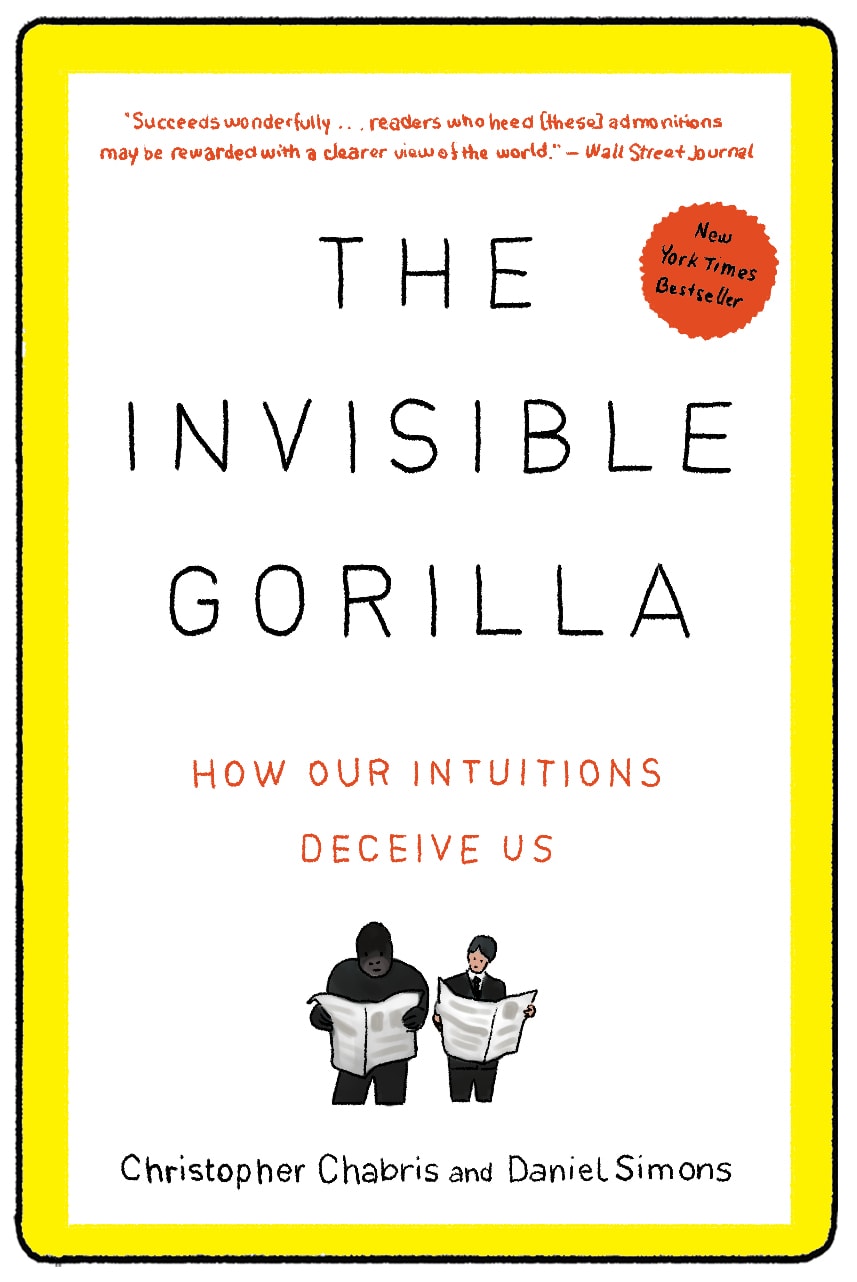

This case supports the existence of inattentional blindness (also known as perceptual blindness.) Chabris and Simons describe the research into this phenomenon in their 2010 book The Invisible Gorilla: How Our Intuitions Deceive Us . The book also describes the serious effect inattentional blindness can have on court cases, our perception of ourselves, and even life and death.

We don’t think that we fail to notice things. After all, if we fail to notice something...we go about our day without noticing that we didn’t notice something. The gorilla experiment shakes this idea up and often makes people uncomfortable.

What is Inattentional Blindness?

Inattentional blindness is a type of blindness that has nothing to do with your ability to see. It has to do with your ability to pay attention to unexpected stimuli. If your capacity is limited to one task or set of stimuli, you may fail to see the unexpected stimuli, even if it’s right in front of you.

Chabris and Simons were not the first psychologists to research this phenomenon. Arien Mack and Irvin Rock coined the term “inattentional blindness” in 1992 and published a book on the phenomenon six years later.

No one expects to see a gorilla walk into a group of people throwing basketballs at each other. (In a similar experiment, Chabris and Simons replaced the gorilla suit with a person carrying an umbrella - inattentional blindness still occurred.) So many people, while focused on a task, don’t.

This experiment shows that sometimes, we literally can’t see things that are right in front of us. Throughout their book, Chabris and Simons discuss the flip side of this. We believe that we see the people passing the basketball.

Inattentional blindness is slightly different than change blindness , which is a type of "blindness" that occurs when we fail to see changes in our environment.

Our memories can be tricky, especially when asked to recall them. We may also believe that we saw or experienced things that have never actually occurred. Both situations can play a role in, for example, the justice system.

Can Multitasking Cause Inattentional Blindness?

Not really; it's closer to the opposite! A Reddit user recently posted that people with ADHD are more likely to see the gorilla, supporting the idea that "focus" is what "blinds" people from the gorilla.

Kenny Conley and Inattentional Blindness

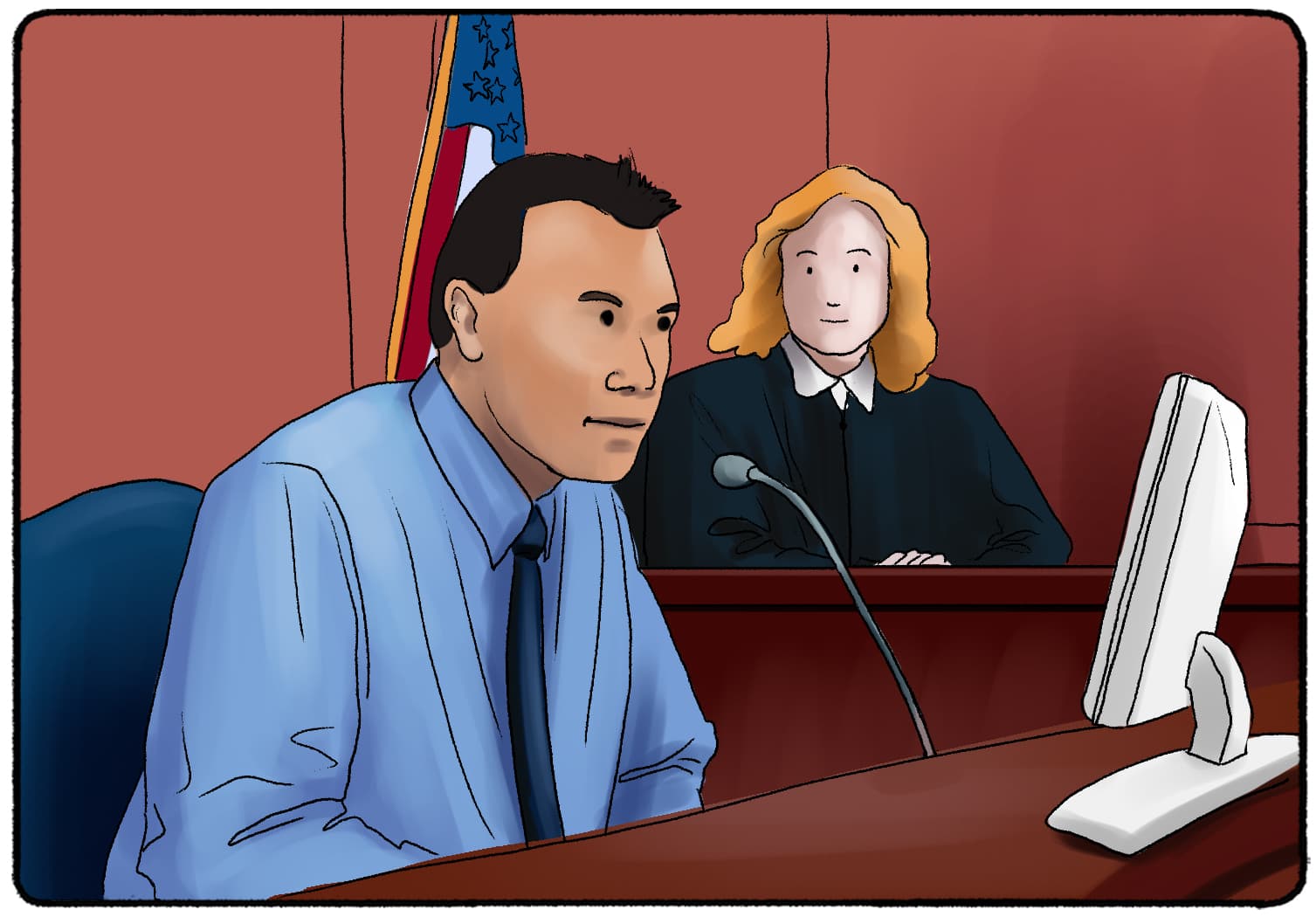

During their research, Chabris and Simons met with Kenny Conley. Conley was a member of the Boston Police Department in 1995. One night, he was chasing a shooting suspect. At the same time, another officer (Michael Cox) was chasing suspects - the officer was undercover, but he was mistaken for one of the suspects. Multiple officers began to assault Cox to the point where Cox was unconscious.

The incident went to trial. Conley was put on the witness stand, for he had been present at the scene of the assault of Michael Cox. But there was just one problem. Conley swore he did not see the assault happen. In his testimony, he says, “I think I would have seen that.” (Sounds much like what people would say after failing to see the gorilla, right?)

Law enforcement officers believed that Conley was lying on the stand. While the officers who assaulted Cox walked free, Conley was charged and put in jail for obstruction of justice and perjury.

But Conley wasn’t lying. He was just so focused on chasing the shooting suspect that he was blind to the assault of Michael Cox. It took ten years of appealing the conviction for Conley to walk free. He was eventually reinstated to his position at the Boston Police Department and received compensation for lost wages.

But Conley’s case is not the only known case of inattentional blindness. Research shows that misidentifications and inattentional blindness are the leading cause of wrongful convictions in this country. The Innocence Project claims that seven out of ten convictions overturned with DNA evidence could be attributed to eyewitness misidentifications. Just this year (2019), the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Curtis Flowers, a man who was accused of killing four people in 1996. Quite a few examples of witness misidentification are present in the history of this case.

Multiple studies have looked specifically at the abilities of eyewitnesses to thefts and other crimes. Turns out, these witnesses are not always reliable . Due to these studies and the conversation about inattentional blindness, multiple states have created policies for juries on how to spot possible witness misidentification and not to rely too heavily on eyewitness testimony.

Inattentional Blindness In Everyday Life

Even if you are not involved in a criminal trial, it’s important to know about inattentional blindness and how it affects our “intuition.” I highly recommend reading The Invisible Gorilla to learn more about inattentional blindness and how it pervades everyday life.

Related posts:

- Inattentional Blindness (Definition + Examples)

- Change Blindness (Definition + Examples)

- Attention (Psychology Theories)

- Dream of Gorilla Meaning (11 Reasons + Interpretation)

- Cognitive Psychology

Reference this article:

About The Author

- Selective Attention Theories

- Invisible Gorilla Experiment

- Cocktail Party Effect

- Stroop Effect

- Multitasking

- Inattentional Blindness

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

But Did You See the Gorilla? The Problem With Inattentional Blindness

The most effective cloaking device is the human mind

Daniel Simons

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Phenom-Gorilla-spotting-631.jpg)

For more than a decade, my colleagues and I have been studying a form of invisibility known as inattentional blindness. In our best-known demonstration, we showed people a video and asked them to count how many times three basketball players wearing white shirts passed a ball. After about 30 seconds, a woman in a gorilla suit sauntered into the scene, faced the camera, thumped her chest and walked away. Half the viewers missed her. In fact, some people looked right at the gorilla and did not see it.

That video was an Internet sensation. So, in 2010, I decided to make a sequel. This time viewers were expecting the gorilla to make an appearance. And it did. But the viewers were so focused on watching for the gorilla that they overlooked other unexpected events, such as the curtain in the background changing color.

How could they miss something right before their eyes? This form of invisibility depends not on the limits of the eye, but on the limits of the mind. We consciously see only a small subset of our visual world, and when our attention is focused on one thing, we fail to notice other, unexpected things around us—including those we might want to see.

Consider, for instance, a famous 1995 incident in which police were in hot pursuit of four suspects driving away from the scene of a shooting. After cornering the suspects, the first police officer on the scene, Michael Cox, chased one of them on foot. Other officers arriving on the scene mistakenly thought Cox was a suspect and beat him. Meanwhile, another officer, Kenny Conley, had taken up pursuit of the same suspect and ran right past the altercation. Conley claimed not to have seen Cox or his assailants, and he was convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice.

Conley’s conviction raised an intriguing legal issue: Could an eyewitness actually fail to notice an assault like that one? Last year, psychology professor Christopher Chabris and I decided to put Conley’s alibi to the test. Although we could not simulate a high-speed police pursuit, we could extract the most critical element: Conley’s focus on pursuing a suspect. In our experiment, we asked participants to jog behind an assistant and count the number of times he touched his hat. As they jogged, they ran past a staged fight in which two men appeared to be beating a third. Even in broad daylight, over 40 percent missed the fight. At night, 65 percent missed it. In light of such data, Conley’s statement that he didn’t even see Cox or his assailants was plausible.

Indeed, most of us are unaware of the limits of our attention—and therein lies the real danger. For instance, we may talk on the phone and drive because we are mistakenly convinced that we would notice a sudden event, such as a car stopping short in front of us.

Inattentional blindness does have an upside. Our ability to ignore distractions around us allows us to retain our focus. Just don’t expect your partner to be charitably disposed when your focus on the television renders her or him invisible.

[×] CLOSE

VIDEO: The Monkey Business Illusion

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

The Invisible Gorilla: A Classic Experiment in Perception

The invisible gorilla experiment

A couple of paragraphs above, we gave you the same instructions that Chabris and Simons gave to a group of student volunteers before doing the experiment.

When the participants finished watching the video, they were asked the following questions (answer them as well if you watched the video):

- “Did you notice anything unusual while counting the passes?”

- “Did you notice anything else besides the players?

- “Or did you notice anyone other than the players?”

- “Did you notice a gorilla?”

The last question was the one that surprised the volunteers of the invisible gorilla experiment the most. At least 58% of them. Whenever the experiment has been repeated, the percentage of surprise is more or less the same. Yes, there was a gorilla in the video, but more than half of the people didn’t notice it. Did you see it?

The reactions to what happened

The first time the invisible gorilla experiment was conducted, and all subsequent ones, most of those who participated and didn’t notice the presence of the gorilla were amazed at how clear it all was! It seemed impossible to them that they had overlooked something so obvious.

When they’re asked to watch the video again, they all see the gorilla without a problem. Some think that they’ve been shown two different videos, but, of course, this isn’t the case. This experiment won the Ig Nobel Prize. This is an award given to those scientific activities that “first make you laugh and then make you think”.

Why are so many people blind to such an obvious image in the video? That’s the big question that comes out of this. It’s also striking that so many people refuse to accept that their eyes and perception are deceiving them. They think they’re seeing everything correctly, and yet they haven’t seen something so obvious.

Introduction

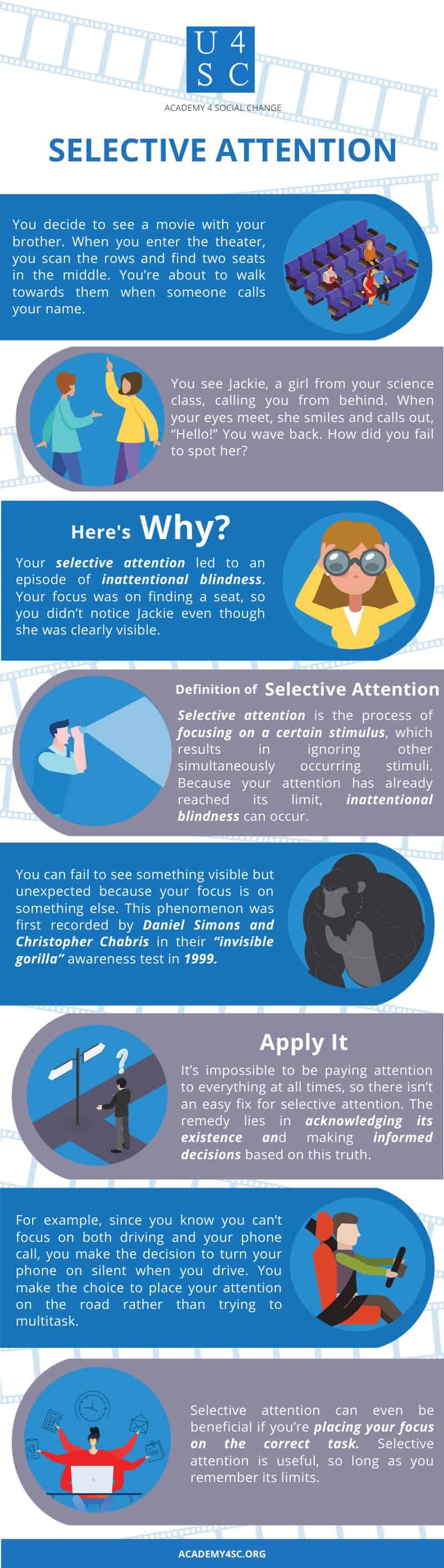

You decide to see the latest thriller with your younger brother. You purchase your tickets, snacks, and drinks. All that’s left is to secure your seats. When you enter the theater, you scan the rows, looking for the perfect spot. Lo and behold, you find one: two open seats in the middle. You’re about to walk towards them when someone calls your name.

You trace the noise back two rows and see Jackie, a girl from your science class. She’s waving both her arms enthusiastically. When your eyes meet, she smiles and calls out, “Hello!” You wave back. How did you fail to spot her?

Your selective attention led to an episode of inattentional blindness. Your focus was on finding a seat, so you didn’t notice Jackie even though she was clearly visible.

Definition/Selective Attention

Selective attention is the process of focusing on a particular stimulus or stimuli, which results in the ignoring of other simultaneously occurring stimuli. Because your attention has already reached its limit, inattentional blindness can occur. You can fail to see something fully visible but unexpected - like a classmate at the movie theater - because your focus is on something else - like finding a seat. This phenomenon was famously recorded by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in their “invisible gorilla” awareness test.

The study was conducted in 1999 at Harvard University. It involved a short video of people in white t-shirts and black t-shirts passing a basketball to people in the same colored shirt. Participants were asked to watch this video and count the number of passes the white team made. Most could correctly list the number of passes and thought it was a relatively easy task. Yet despite this, over half of the participants failed to notice a person in a gorilla suit walk between the basketball players, stand and face the camera, bang their chest, and walk offscreen.

This goes against nearly everyone’s intuition: we’d expect to be able to spot such an obvious occurrence. Yet repeated studies have gathered similar results: we aren’t as observant as we like to think. If we don’t expect to see something, odds are we won’t notice it. Selective attention has its benefits, but it can cause you to miss out on something as obvious as a gorilla thumping its chest.

Participants didn’t suffer when they failed to spot a gorilla while counting passes, but the consequences of selective attention can be far reaching and dangerous. Similar studies to the Invisible Gorilla Test have been replicated with experts and they faired only slightly better than the participants in the original study did. When looking closely at lung scans for signs of cancer, most radiologists did not see the superimposed picture of a gorilla until it was pointed out to them. If they failed to notice something as out of place as a gorilla, it stands to reason that even experts can be blind to medical anomalies or early warning signs of illnesses.

A much more commonplace example stems from the false belief that there’s such a thing as true, effective multitasking. For example, while you might never text and drive, you may on occasion answer a phone call while you commute. “It’s not like I’m taking my eyes off the road,” you may argue, “I should be able to listen and look at the same time.” However, vision has little to do with the problem of inattentional blindness. In fact, of the participants who failed to spot the gorilla, many of them looked directly at it. So even though you’re looking at the road, that doesn’t mean you can keep track of every detail you see. Your attention is still being divided, leaving you in danger of inattentional blindness, such as not seeing a motorcycle switch into your lane.

It’s impossible to be paying attention to everything at all times, so there isn’t an easy fix for selective attention. Rather, the remedy lies in acknowledging its existence and making informed decisions based on this truth. For example, since you know you can’t focus on both driving and your phone call, you make the decision to turn your phone on silent when you drive or leave it in the backseat. You make the choice to place your attention on the road rather than trying to multitask. Selective attention can even be beneficial if you’re placing your focus on the correct task. While you won’t notice if your phone lights up with new messages in the back seat, you will notice the car in front of you slowing down. Selective attention is useful, so long as you remember its limits.

Think Further

- Recall a time when you were so focused on your task, you failed to notice a change in your environment. What were you doing? What did you fail to notice?

- What are some other dangers of selective attention and inattentional blindness?

- What are some other benefits of selective attention?

Teacher Resources

Sign up for our educators newsletter to learn about new content!

Educators Newsletter Email * If you are human, leave this field blank. Sign Up

Get updated about new videos!

Newsletter Email * If you are human, leave this field blank. Sign Up

Infographic

This gave students an opportunity to watch a video to identify key factors in our judicial system, then even followed up with a brief research to demonstrate how this case, which is seemingly non-impactful on the contemporary student, connect to them in a meaningful way

This is a great product. I have used it over and over again. It is well laid out and suits the needs of my students. I really appreciate all the time put into making this product and thank you for sharing.

Appreciate this resource; adding it to my collection for use in AP US Government.

I thoroughly enjoyed this lesson plan and so do my students. It is always nice when I don't have to write my own lesson plan

Sign up to receive our monthly newsletter!

- Academy 4SC

- Educators 4SC

- Leaders 4SC

- Students 4SC

- Research 4SC

Accountability

Missing the gorilla: People prone to 'inattention blindness' have a lower working memory capacity

University of Utah psychologists have learned why many people experience "inattention blindness" -- the phenomenon that leaves drivers on cell phones prone to traffic accidents and makes a gorilla invisible to viewers of a famous video.

The answer: People who fail to see something right in front of them while they are focusing on something else have lower "working memory capacity" -- a measure of "attentional control," or the ability to focus attention when and where needed, and on more than one thing at a time.

"Because people are different in how well they can focus their attention, this may influence whether you'll see something you're not expecting, in this case, a person in a gorilla suit walking across the computer screen," says the study's first author, Janelle Seegmiller, a psychology doctoral student.

The study -- explaining why some people are susceptible to inattention blindness and others are not -- will be published in the May issue of The Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition .

Seegmiller conducted the research with two psychology faculty members -- Jason Watson, an assistant professor, and David Strayer, a professor and leader of several studies about cell phone use and distracted driving.

"We found that people who notice the gorilla are better able to focus attention," says Watson, also an assistant investigator with the university's Brain Institute.

'The Invisible Gorilla' Test for Inattention Blindness

The new study used a video made famous by earlier "inattention blindness" research featured in the 2010 book "The Invisible Gorilla," by Christopher Chabris, a psychologist at Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., and Daniel Simons, a psychologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The video depicts six actors passing a basketball. Viewers are asked to count the number of passes. Many people are so intent on counting that they fail to see a person in a gorilla suit stroll across the scene, stop briefly to thump their chest, and then walk off.

Seegmiller, Watson and Strayer did a new version of the older experiments, designed to determine the reason some people see the gorilla and others miss it.

Why are the results important?

"You can imagine that if you're driving and road conditions aren't very good, unexpected things can happen, and individuals with better control over attention would be more likely to notice those unexpected events without having to be explicitly told to watch for them," Seegmiller says.

Watson adds: "The potential implications are that if we are all paying attention as we are driving, some individuals may have enough extra flexibility in their attention to notice distractions that could cause accidents. That doesn't mean people ought to be self-distracting by talking on a cell phone while driving -- even if they have better control over their attention. Our prior research has shown that very few individuals [only 2.5 percent] are capable of handling driving and talking on a cell phone without impairment. "

Strayer has conducted studies showing that inattention blindness explains why motorists can fail to see something right in front of them -- like a stop light turning green -- because they are distracted by the conversation, and how motorists using cell phones impede traffic and increase their risk of traffic accidents.

Linking Working Memory to Inattention Blindness

A key question in the study was whether people with a high working memory capacity are less likely to see a distraction because they focus intently on the task at hand -- a possibility suggested by some earlier research -- or if they are more likely to see a distraction because they are better able to shift their attention when needed.

The new study indicates the latter is true.

"We may be the first researchers to offer an explanation for why some people notice the gorilla and some people don't," Watson says.

Working memory capacity "is how much you can process in your working memory at once," Seegmiller says. "Working memory is the stuff you are dealing with right at that moment, like trying to solve a math problem or remember your grocery list. It's not long-term memory like remembering facts, dates and stuff you learned in school."

The researchers studied working memory capacity because it "is a way that we measure how some people can be better than other people at focusing their attention on what they're supposed to," she adds.

The Utah study began with 306 psychology students who were tested with the gorilla video, but about one-third then were excluded because they had prior knowledge of the video. That left 197 students, ages 18 to 35, whose test results were analyzed.

First, the psychologists measured working memory capacity using what is known as an "operation span test." Participants were given a set of math problems, each one of which was followed by a letter, such as "Is 8 divided by 4, then plus 3 equal to 4? A."

Each participant was given a total of 75 of these equation-letter combinations, in sets of three to seven. For example, if a set of five equations ended with the letters A, C, D, G, P, the participant got five points for remembering ACDGP in that order. After each set of equations and letters, participants were asked to recall all the letters of each set. A few participants scored a perfect 75 score.

Participants had to get 80 percent of the math equations right to be included in the analysis. That was to ensure they focused on solving the math problems and not just on remembering the letters after the equations.

Next, the participants watched the 24-second Chabris-Simons gorilla video, which had two, three-member basketball teams (black shirts and white shirts) passing balls. Participants were asked to count bounce passes and aerial passes by the black team. Then they were asked for the two pass counts and whether they noticed anything unusual.

To remove a potential bias in the study, the researchers had to make sure the people who noticed the gorilla also were counting basketball passes; otherwise, people who weren't counting passes would be more likely to notice the distraction. So only video viewers who were at least 80 percent accurate in counting passes were analyzed.

The Utah psychologists got results quite similar to those found by Simons and Chabris in their original study in 1999: of participants who were acceptably accurate in counting passes, 58 percent in the new study noticed the gorilla and 42 percent did not.

But the Utah study went further: Again analyzing only accurate pass counters, the gorilla was noticed by 67 percent of those with high working memory capacity but only by 36 percent of those with low working memory capacity.

In other words, "if you are on task and counting passes correctly, and you're good at paying attention, you are twice as likely to notice the gorilla compared with people who are not as good at paying attention," Watson says. "People who notice the gorilla are better able to focus their attention. They have a flexible focus in some sense."

Put another way, they are better at multitasking.

Future studies should look for other possible explanations of why some people suffer inattention blindness and others do not, including differences in the speeds at which our brains process information, and differences in personality types, the Utah psychologists say.

For a link to the gorilla video, see: www.theinvisiblegorilla.com

- ADD and ADHD

- Learning Disorders

- Educational Psychology

- Intelligence

- Mental confusion

- Social psychology

- Adult attention-deficit disorder

- Head injury

- Delayed sleep phase syndrome

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Utah . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Janelle K. Seegmiller, Jason M. Watson, David L. Strayer. Individual differences in susceptibility to inattentional blindness. . Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition , 2011; DOI: 10.1037/a0022474

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Can the Heart Heal Itself? New Study Says It Can

- Tinkering With 'Clockwork' Mechanisms of Life

- Quantum Teleportation Over Busy Internet Cables

- Mysteries of Icy Ocean Worlds

- Safer Spuds: Removing Toxins from Potatoes

- Gruel Eaten by Early Neolithic Farmers

- Dark Energy 'Doesn't Exist'

- Nerve Regeneration After Spinal Cord Injury

- Laser-Based Artificial Neuron: Lightning Speed

- Large Hadron Collider Regularly Makes Magic

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

Christos Vachtsiavanos

- Human Behavior

The Invisible Gorilla experiment: What are the limits of our attention?

- May 7, 2023

- By Christos Vachtsiavanos

The Invisible Gorilla experiment is a well-known psychological study from 1999, and highlights our cognitive biases and the limitations of our attention.

This now-classic research project has shown that selective attention has implications for various aspects of our lives, from decision-making to personal safety.

In the next 4 minutes, you will explore the Invisible Gorilla experiment, the phenomena of selective attention and inattentional blindness, and examples of inattentional blindness in real-life scenarios.

Also, I will mention the consequences of inattentional blindness and hopefully provide helpful ways to deal with its effects.

The Invisible Gorilla experiment

In the late 1990s, psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris conducted an experiment in which they instructed participants to watch a video of two groups of people passing a basketball.

Participants were instructed to count the number of passes made by one team while ignoring the other team’s passes. An easy task that requires some amount of focus.

However, the video included a small surprise.

While the people were throwing the ball at one another, a person wearing a gorilla suit walked through the scene, stopped in the middle, pounded their chest, and then walked off.

That’s too crazy to be ignored, right?

Well, the researchers found that despite the gorilla’s prominent appearance in the video, around 50% of the participants did not notice it.

This phenomenon is known as inattentional blindness and occurs when an individual is so focused on a particular task or stimulus that they overlook other unexpected stimuli in their environment.

That was the Invisible Gorilla experiment, which is now considered a classic one in the field of human behavior.

Selective attention: What does the Invisible Gorilla experiment teach us?

The Invisible Gorilla experiment teaches us that human attention is selective and limited.

We cannot process all the information presented to us at once, so we must selectively attend to specific stimuli while filtering out others. That allows us to focus on essential tasks but can also cause us to overlook unexpected or potentially critical events.

Inattentional blindness is not a sign of incompetence or lack of intelligence. It instead highlights the inherent limitations of human attention.

Understanding this phenomenon can help us become more aware of our cognitive blind spots and develop solutions to mitigate their harmful effects.

The police pursuit example

One real-life example that illustrates the consequences of selective attention and inattentional blindness is a 1995 police pursuit incident.

During a high-speed chase, police officer Michael Cox chased a suspect on foot while other officers arrived at the scene. The arriving officers mistakenly believed Cox was a suspect and began assaulting him.

At the same time, another officer, Kenny Conley, continued pursuing the same suspect on foot and ran past the altercation without noticing it.

Conley was later convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice, as he claimed not to have seen the assault.

Researchers Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons conducted a study to test the plausibility of Conley’s claim.

During their experiment, participants jogged behind an assistant, counting the number of times the assistant touched their hat.

While jogging, the participants passed a staged fight.

The results showed that more than 40% of the participants missed the fight in broad daylight, and 65% missed it at night.

This experiment showcased that Conley’s claim was plausible, proving the powerful effects of inattentional blindness.

The radiologist experiment

Another example that highlights the implications of the Invisible Gorilla experiment in professional contexts involved radiologists.

In a study conducted by psychological scientists Trafton Drew, Melissa Vo, and Jeremy Wolfe, 24 experienced radiologists were asked to examine CT scans of patients’ lungs, searching for nodules that could indicate lung cancer.

However, in a set of scans, the researchers inserted a small image of a gorilla into the lung scan.

Despite the gorilla being 48 times larger than a typical nodule, 83% of the radiologists failed to notice the gorilla while focusing on identifying the cancerous nodules.

This study shows that even highly trained professionals are susceptible to inattentional blindness when their attention is focused on a specific task.

How can inattentional blindness hurt us?

Selective attention can significantly help us when we need to focus on a specific task for a given period, but leading to inattentional blindness can also hurt us in different ways:

- Decision-making: Focusing on a single aspect of a complex decision can lead to neglecting other essential factors, resulting in mediocre outcomes.

- Work performance : Selective attention can cause critical mistakes in tasks that require different skills to deal with a specific problem.

- Personal safety: In high-stress situations or while multitasking, we may overlook potential hazards, increasing the risk of accidents or injury.

- Interpersonal relationships: Selective attention can prevent us from understanding others’ perspectives or empathizing with their emotions, leading to miscommunication and conflict.

7 ways to deal with inattentional blindness

Selective attention is a natural cognitive process, but we need to find ways to mitigate the potential negative consequences of its by-product, inattentional blindness.

Here are 7 ways to deal with inattentional blindness:

1. Increasing awareness

Recognize that your attention has limitations and that you may miss things even when you believe you are paying close attention.

2. Practicing mindfulness

By trying out mindfulness exercises, you can better understand what your mind is focused on and, in that way, enhance focus and self-awareness in the long term.

3. Breaking tasks into smaller parts

By dividing tasks into smaller, more manageable pieces, you can allocate attention more effectively and, as a result, reduce the chances of overlooking critical details.

4. Taking breaks

Taking breaks is equally important as doing focused work. Regular breaks can prevent mental fatigue, which can exacerbate inattentional blindness.

5. Collaborating with others

We all have flaws and different qualities as human beings. That’s why working in teams can help compensate for individual attentional limitations; different perspectives increase the likelihood of identifying critical information.

6. Limiting distractions

Create an environment that minimizes external distractions, allowing you to focus more effectively on the task at hand.

7. Prioritizing tasks

Rank tasks by importance and allocate your attention accordingly to ensure you address the most critical aspects first.

The Invisible Gorilla experiment is a reminder of the limitations of our attention as human beings.

By understanding how selective attention and inattentional blindness work, we can become more aware of our cognitive biases and work to counteract any possible adverse outcomes.

Also, if we can find ways to enhance our focus while addressing the effects of inattentional blindness, we can enjoy better decision-making, improved work performance, increased personal safety, and more effective interpersonal communication .

The ultimate purpose is to acknowledge, on the one hand, the limits of our attention and, on the other hand, to address them whenever possible.

In that way, we can navigate the complexities of the modern world more effectively and purposefully.

If you want to receive more posts like this to your inbox every week, subscribe to my newsletter below for free.

Let’s connect on LinkedIn: Christos Vachtsiavanos | LinkedIn

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the invisible gorilla experiment, and what does it reveal about human attention.

The Invisible Gorilla experiment, conducted by psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris, demonstrates the concept of inattentional blindness, where people can miss obvious things in their visual field when their attention is focused elsewhere. This experiment reveals that human attention is selective and has its limitations, showing that we cannot process all the information in our environment simultaneously.

How does selective attention impact our daily lives?

Selective attention impacts our daily lives by allowing us to focus on specific tasks or stimuli, filtering out irrelevant information. While this helps us concentrate and perform tasks efficiently, it can also lead us to overlook important or unexpected events, affecting decision-making, work performance, personal safety, and interpersonal relationships.

Can inattentional blindness be considered a flaw in human cognition?

Inattentional blindness is not necessarily a flaw in human cognition but rather a byproduct of the way our attention mechanisms are designed. It highlights the inherent limitations of our attentional focus, showing that while we can concentrate on certain aspects of our environment, this concentration can cause us to miss other, potentially significant information.

How can inattentional blindness affect professional performance?

Inattentional blindness can affect professional performance by leading to critical mistakes, especially in tasks requiring comprehensive attention to detail. For instance, healthcare professionals may overlook anomalies in diagnostic images, or law enforcement officers might miss crucial evidence during investigations, demonstrating the need for strategies to mitigate these effects.

What strategies can help mitigate the effects of inattentional blindness?

Strategies to mitigate inattentional blindness include increasing awareness of attentional limitations, practicing mindfulness to enhance focus, breaking tasks into smaller parts, taking regular breaks to prevent mental fatigue, collaborating with others to benefit from diverse perspectives, limiting distractions, and prioritizing tasks to allocate attention effectively.

Why is understanding the Invisible Gorilla experiment important?

Understanding the Invisible Gorilla experiment is important because it sheds light on the selective nature of human attention and the phenomenon of inattentional blindness. By recognizing these aspects of human cognition, we can develop better strategies for managing our attention, improving our decision-making processes, enhancing work performance, ensuring personal safety, and fostering more effective communication in interpersonal relationships.

What role does mindfulness play in combating inattentional blindness?

Mindfulness plays a significant role in combating inattentional blindness by increasing self-awareness and the ability to notice present-moment experiences without judgment. By practicing mindfulness, individuals can improve their focus, become more aware of their surroundings, and potentially reduce the instances of missing important stimuli due to focused attention elsewhere.

How can teamwork help in reducing the effects of inattentional blindness?

Teamwork can help reduce the effects of inattentional blindness by bringing together diverse perspectives and compensating for individual attentional limitations. Working in a team allows for multiple sets of eyes and ears to observe different aspects of a situation, increasing the likelihood of identifying critical information that might be missed by an individual working alone.

Latest Posts

Emotional words vs. Power words: Which ones should you use and when?

8 reasons why Trump won & what to expect next

Get free weekly tips, every sunday, i share tips on communication, writing, human behavior, marketing, and more..

Contact Info

- [email protected]

- 1:1 Consultation

- Content Writing

- Weekly Tips

- Privacy Policy

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The original, world-famous awareness test from Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris. Get our new book, *** Nobody's Fool: Why We Get Taken In and What We Ca...

Jul 11, 2010 · Invisible gorilla basketball video highlights inattentiveness. These confounding findings from cognitive psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris detailed in a 1999 study revealed how ...

Nov 1, 2023 · In 1999, Chris Chabris and Dan Simons conducted an experiment known as the “Invisible Gorilla Experiment.” They told participants they would watch a video of people passing around basketballs. In the middle of the video, a person in a gorilla suit walked through the circle momentarily.

To demonstrate this effect they created a video where students pass a basketball between themselves. Viewers asked to count the number of times the players with the white shirts pass the ball often fail to notice a person in a gorilla suit who appears in the center of the image (see Invisible Gorilla Test ), an experiment described as "one of ...

After about 30 seconds, a woman in a gorilla suit sauntered into the scene, faced the camera, thumped her chest and walked away. Half the viewers missed her. In fact, some people looked right at ...

Nov 9, 2022 · The invisible gorilla experiment. A couple of paragraphs above, we gave you the same instructions that Chabris and Simons gave to a group of student volunteers before doing the experiment. When the participants finished watching the video, they were asked the following questions (answer them as well if you watched the video):

This phenomenon was famously recorded by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in their “invisible gorilla” awareness test. Experiment. The study was conducted in 1999 at Harvard University. It involved a short video of people in white t-shirts and black t-shirts passing a basketball to people in the same colored shirt.

May 19, 2010 · Mid-way through the video, a gorilla walks through the game, stands in the middle, pounds his chest, then exits. ... And you both created your invisible gorilla experiment over 10 years ago to ...

Apr 18, 2011 · The video depicts six actors passing a basketball. Viewers are asked to count the number of passes. Many people are so intent on counting that they fail to see a person in a gorilla suit stroll ...

May 7, 2023 · The Invisible Gorilla experiment. In the late 1990s, psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris conducted an experiment in which they instructed participants to watch a video of two groups of people passing a basketball. Participants were instructed to count the number of passes made by one team while ignoring the other team’s passes.